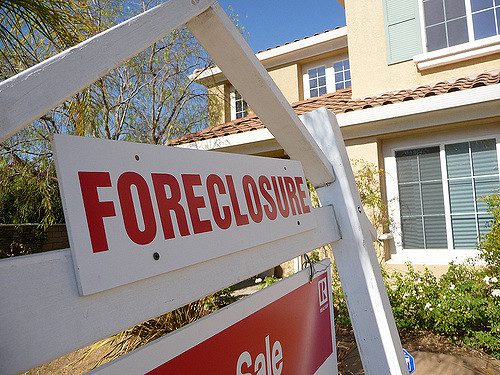

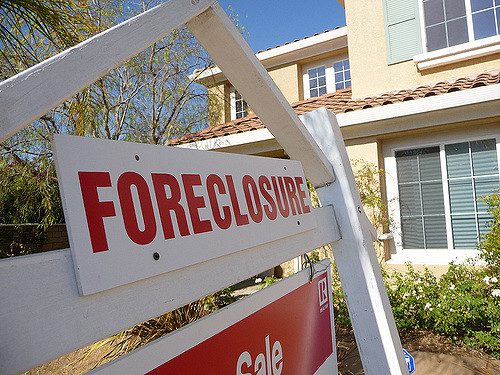

In more than a quarter century of community development work, Tisler, who has joined the National Community Reinvestment Coalition as director of its Housing Counseling Network, saw many challenges during his 12 years with NHS, but none greater than the foreclosure crisis that started with the collapse of the housing market 10 years ago.

“Between flipping, mortgage fraud, etc., we saw a lot of people get hurt,” recalls Tisler. “At first, when people fell behind (on their mortgage payments) it was easy to get them caught up. Then we saw the recession really kick in and people lost their jobs and there were no jobs to be had, which made dealing with the issue that much harder. Now we have a tax-foreclosure crisis that is increasing at an alarming rate. So you have some of your large organizations saying the (foreclosure) crisis is over, but there is a new emergency now hitting the elderly hard. And that is tax foreclosures.”

In fact, he calls tax foreclosure perhaps the greatest challenge facing affordable housing organizations, particularly those in Rust Belt states that have not recovered from the Great Recession as quickly as other states. Cities like Cleveland and Detroit have been hit especially hard.

In Ohio, counties are allowed to bundle and sell tax liens, or the legal right to collect a debt, to outside investors after a property owner has failed to pay taxes for more than one year. Investors buy the liens because they make money by tacking on interest rates of up to 18 percent. The lien buyers can foreclose on homes if the property owners don’t pay their debts. Cuyahoga County, which includes Cleveland, first sold delinquent tax liens to private investors in 1999. In the fall of 2016, it reported that the practice had recouped more than $188 million for the county and local governments, including school districts, who were owed the tax money. That’s great for local governments, but disastrous for many vulnerable residents.

Otherwise, in many ways, the affordable housing industry still looks the same as it did when he joined NHS in 2005, he says. “It still has the connotation that many people put to it in terms of race, demographics, etc. In this political climate it has become easier to point that out,” Tisler says. “We don’t want renters in our community, we don’t want ‘those people’ in our community. But if you ask people if they want housing that is affordable, the answer is yes, everyone is looking for a home they can afford.”

As a result, he adds, “we are not going to put ourselves out of a job any time soon. That is what a civil society does … helps those who are less fortunate. But putting that responsibility solely on the shoulders of the nonprofit world to make it happen seems unfair.” That’s why partnerships are so critical, and Tisler points to the Wells Fargo-NeighborWorks LIFT program as one example of a partnership that is making a positive difference.

A version of this post originally appeared on the NeighborWorks blog.

(Image: Courtesy of BasicGov, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Comments