The following is an update to a 2012 Rooflines piece by Van Temple about the struggle of a mobile home community evicted from its grounds. Temple's piece ends in hard-won success, with expectation that the residents of the mobile home community would get to stay together in a new affordable home community. But a year later, the community is still as far as ever from achieving that goal.

Background

Some years ago, a group of low-income immigrant families organized around the decrepit conditions of the Dogwood Mobile Home Park in Sussex County, Delaware. In retaliation for the complaints, the owner of the mobile home park issued eviction notices to residents.

But rather than turn on each other, the families banded together and challenged the eviction in successive state courts until they had negotiated an additional year’s stay of eviction. At the same time, the families formed the Morris Mill Pond Cooperative and partnered with the Delaware Housing Coalition in an attempt to purchase the land from the owner and establish it as a cooperative.

The owner of the mobile home park refused any offer to purchase the property, and with the temporary stay of eviction set to expire, the families were forced to leave. The community remained in contact and under the leadership of Rene Arauz, community activist and longtime resident of the DMHP, continued to look for land in pursuit of the dream of collective homeownership for themselves and their families.

In 2005, a new opportunity arose with the formation of the Diamond State Community Land Trust (DSCLT) which, shortly after its founding, partnered with the former Morris Mill Pond Cooperative, now called New Horizons Cooperative. The partnership was a strong one. Not only did the community land trust approach fit the needs of the New Horizons Community perfectly, but the specific goals of the two organizations were highly complementary.

New Horizons provided a strong constituency with both an acute need for permanent, affordable housing and, even more importantly, the will to organize and fight for their community—the most critical element of any CLT.

In turn, DSCLT provided New Horizons with the critical development capacity needed to find a suitable location, aid in planning and design, deal with local zoning, building, and environmental codes, and assist with public outreach.

After a two-year search, the group settled on a 42-acre site in Sussex County near Trap Pond State Park. Half of the site would be developed for housing, recreation and community-supported agriculture, the other half would remain as forest.

In 2008, DSCLT and New Horizons Cooperative submitted plans for the 50-unit cluster development, to be called New Horizons Community, to the Sussex County Planning and Zoning Commission. The night of the hearing arrived and about 75 individuals showed in opposition to New Horizons.

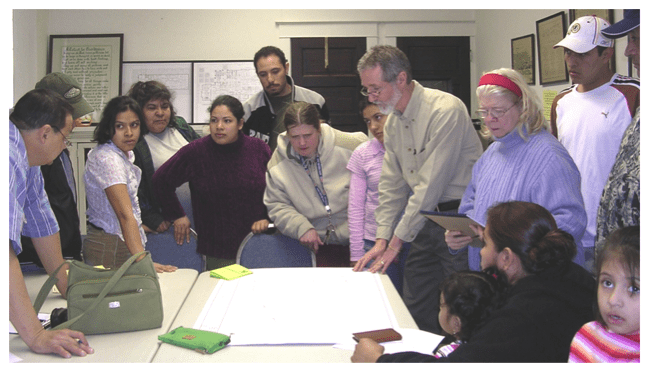

New Horizons Community planning and design meeting, 2008. Photo courtesy of Amy Walls, DSCLT.

On July 14, 2010, the commission denied approval, with only one commissioner speaking out saying the neighborhood development proposal met planning and zoning requirements, and voting to approve.

The Case Goes to Court

DSCLT and New Horizons immediately appealed the decision to the Sussex County Council, who upheld the commission’s decision, again with one council member voting to approve and voicing his opinion that the New Horizons application met county code.

In November 2010, DSCLT initiated legal action against the county. They had a strong case. Not only had DSCLT not asked for a single variance with the New Horizons proposal, which was in full compliance with local zoning, but the proposed development was in accordance with the 2008 Sussex County comprehensive plan, which had even mentioned DSCLT by name as a partner for the expansion of “shared equity projects” in the county.

Two complaints were filed, one in superior court alleging violation of the due process clause on the part of the Planning and Zoning Commission and county council, the second with the State Division of Human Relations and the regional HUD office, located in Philadelphia. This complaint alleged violation of the Fair Housing Act on the part of the commission, whose decision had clearly been based on the national origin of the members of the New Horizons Cooperative.

Short-Term Success

Ultimately, after a two-year legal process and much legal maneuvering by the county, a consent decree was filed by the U.S. Department of Justice, which ordered the county and commission to reconsider the New Horizons plan based solely on the applicable zoning and land-use laws and barring them from using injunctive measures to delay the development. The decision further ordered that the county and commission:

“Undertake an affordable and fair marketing plan to encourage the development of housing opportunities, including affordable housing and housing developed under the moderately priced housing unit program and the Sussex County rental program, that are available and accessible to all residents of Sussex County regardless of race, color, or national origin.”

Finally, the DOJ ordered that the County pay $750,000 to DSCLT in compensatory damages, an amount which, while nowhere near the direct expense and opportunity costs incurred by DSCLT over the course of four years, was at least symbolic of the county’s responsibility and wrongdoing.

One Year Later

In December 2012, Sussex County appointed Brandy Nauman as the new fair housing compliance officer. Nauman had previously been instrumental in the development and implementation of the Moderately Priced Housing Unit (MPHU) program for both homeownership and rental affordable housing opportunities during her time at the Sussex County Community Development and Housing Office. Over the past year, she has worked with the Delaware State Planning Commission and the DOJ on revising, updating, and enforcing Sussex County’s Affordable and Fair Housing Marketing Plan.

However, during the three years since the commission and council’s rejection of the initial plan, circumstances at the state level had changed. In fact, in 2010, no sooner had the council rejected DSCLT’s appeal, the DNREC updated the state’s storm water and waste water regulations. The new regulations were far more stringent than those in place in 2008 and would have required the construction of an on-site wastewater facility in the proposed New Horizons development due its proximity to state parkland. At the time of the original application, underground septic tanks were acceptable in the area where the proposed New Horizons development would have been located. Such a new requirement would have made a 50-unit development on the site economically unfeasible, and the Trap Pond State Park location had to be abandoned.

The ten-year struggle for New Horizons has also been a war of attrition, one which has seen the scattering of the community. Today, only four or five of the original families remain actively committed to the search for a new location. They continue to be led by Rene Arauz, who has maintained the relationship with Diamond State CLT.

The coalition’s priorities have shifted as well. The real estate market in Sussex County has cooled since the burst of the housing bubble in 2007, and DSCLT and the remaining families have begun searching for property within local towns in Sussex County. “The goal now is community integration, not seclusion,” says Amy Walls, board president of Diamond State Community Land Trust. This new direction coincides with a renewed push by some housing policy experts for stronger and more effective inclusionary housing policies, and presents both new challenges and opportunities in the ongoing fight for affordable housing and community integration nationwide.

A longer version of this article was featured in the Cornerstone Partnership's website and can be read here.

Comments