Yes, the federal government is back in business.

After 16 days and untold billions in lost earnings and wasted dollars, the Republican extortionists more or less threw in the towel, released their hostages on temporary parole until February, and snuffled back to their hiding places, bloodied, but I suspect unchanged.

But something else has changed, though, which bodes ill for our future as a civilized society.

What we have just seen, I fear, is the final death blow to an era that began in the 1930s with the New Deal, an era when the federal government was deeply engaged in addressing the social and economic issues of the nation, the future of its cities, and the fundamental inequalities of condition and opportunity that remain so much part of our society.

Last week I was at the Remaking Cities Congress in Pittsburgh, hanging out with over 300 politicians, architects, planners, academics and community activists. What struck me there is how much the conversation about the federal government has fundamentally changed in the last few weeks.

Admittedly, we’ve been talking about the declining role of the federal government in the cities, in economic opportunity and in racial justice, for decades, at least since the Reagan era. And we’ve been talking about it more in the last few years as a right-wing Supreme Court has rolled back voter rights, and self-imposed budget pressures and anemic leadership at the federal level have led to declines in existing programs along with a shortage new ideas or initiatives. But we always talked about it as if it was something provisional, not inevitable, and that somehow, someday, things could change. We thought we could see the New Deal flame still burning, however faintly it might be flickering.

Well, after 80 years, it went out. What the past few weeks proved beyond any serious doubt is that the debate is now and for the foreseeable future between those who believe the federal government should continue to play a useful role as a status quo service provider, maintaining national parks, helping pay for roads or farm supports, funding medical research, and coming to the rescue in the event of natural disaster; and those who believe that even that modest role is far too ambitious, and that such ‘big government’ needs to be reined in before we’re all forced to trade in our cars for monthly light rail tickets, appear before death panels, or put up with Lord knows what other illusory, phantasmagoric horror.

There are some people, including most probably most Rooflines readers, who believe that the federal government should be a force for change, by fostering community and economic revitalization, creating opportunity for the nation’s youth, fighting on behalf of communities of color, and reducing the gaping economic inequities that are creating two increasingly separate and unequal nations in this country, but we have been marginalized. The voices for a continued federal role in the tradition of the New Deal and the Great Society, and the fight for civil rights, are no longer audible. They exist, but are no longer part of the debate in Washington.

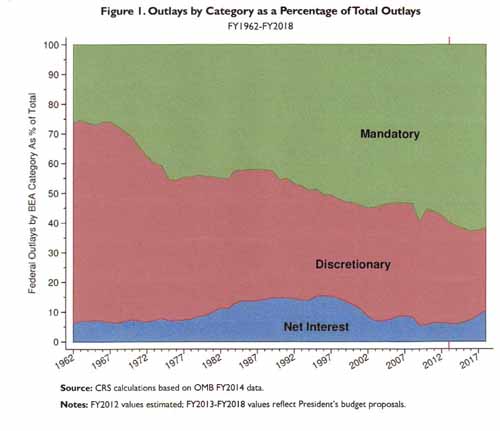

Added to this is the inexorable arithmetic of the federal budget. In 1962, discretionary spending—including defense—made up two-thirds of the federal budget. Today it is 36 percent, of which over half went to defense spending; by 2023, according to the Congressional Budget Office, it will be 24 percent.

With neither Democrats nor Republicans seriously willing to consider increasing taxes, and with both preoccupied with the national debt, domestic discretionary spending will be an increasingly smaller share of the pool. As in recent years, advocates’ energy will be drained fighting to hold onto what little we have, rather than fighting for progressive change. There will be no Marshall Plan for the cities, or for anyone else.

The tragedy of this is that it has happened at a point where not only is American society becoming more unequal, but where inequality is being institutionalized through a dual wage structure and opportunity geography that is moving toward relegating close to half of the nation’s workers and their families in jobs and communities that fail to provide either a decent standard of living or a real chance at upward mobility. Notwithstanding the ‘we are the 99 percent’ rhetoric, that’s not what it’s really about. What Jamie Dimon makes doesn’t really matter. The real gap is between the roughly one-third who have the good jobs and mainly have college degrees, and the half who have the low-paying service jobs and don’t have degrees (the rest is what little is left of the decently-paid working class).

It’s not that we’ve run out of energy and commitment. Go anywhere in the United States, and you’ll find thousands of individuals, organizations, city governments and nonprofits who are working hard to help build a better future for their neighborhoods, their cities and their regions every day. Perhaps over the next many decades their efforts will grow into a national movement, and create the opportunity for a new New Deal, just as it took decades of effort at the state and local levels to lay the groundwork for the first one.

Meanwhile, their efforts are far too few and far between, and moreover, are more often than not made possible by what’s left of the federal funding pipeline. That pipeline won’t disappear at once, of course, but will steadily diminish, making everyone who needs those funds fight harder and harder over the crumbs.

Once upon a time we thought the federal government had our back. That’s over. We’re on our own.

(Photo courtesy of Neighborhoods America)

(Chart: Congressional Research Service)

We are indebted to Alan Mallach for bravely and honestly assessing the implications of the slide we have been in for decades. (While blame is not the issue, I would fault Democrats equally for aiding and abetting the decline by embracing such things as welfare reform, free trade agreements, and financial deregulation.) It can and should inform our thinking and our plans for future community work.