Relationships are critical to promoting affordable housing and community development, but how we invest in those relationships may be even more important.

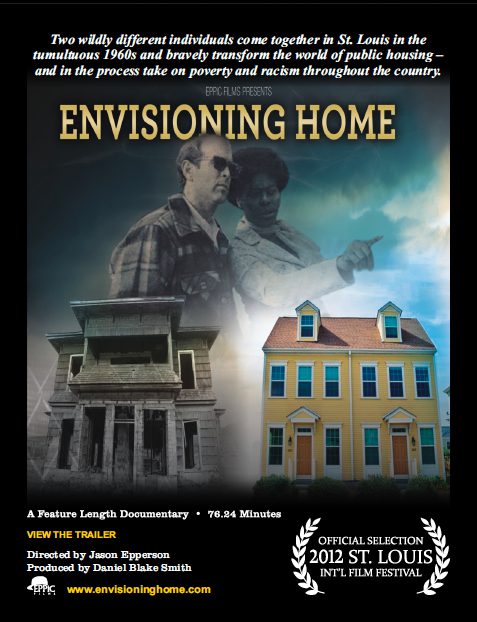

This is the message that stayed with me after the screening of the new documentary film Envisioning Home and the panel discussion hosted by Tufts University’s Department of Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning (UEP) on April 9.

The film, produced and directed by Daniel Blake Smith and Jason Epperson, recounts the efforts of two inspiring leaders who have devoted more than four decades to transforming public housing. Jean King, a housing tenant activist, and Richard Baron, a legal aid attorney, met during the St. Louis rent strike of 1968-69. She knew the residents and the tribulations of living in deteriorating and poorly managed public housing developments. He knew the regulations and legal systems. Their partnership and relationships among mobilized residents and their allies won reforms that continue to shape federally subsidized housing today, such as rents capped to a percentage of household income, designated budget lines for operating expenses, and formal mechanisms for tenant participation. It’s a story about relationships as powerful instruments of institutional change.

The second part of the film traces the growth of McCormack Baron Salazar, a St. Louis-based company, from its first mixed-income, mixed-finance housing developments in the 1970s to the nationwide enterprise it is today. We tour numerous examples of people-centered and energy efficient design and access to educational, employment, health, recreational, and cultural amenities. This is also a story about relationships. Relationships brought together private finances and multiple streams of federal, state, and local funding, connected property managers with residents, and housers partnered with neighborhood service providers.

The discussion among scholars and practitioners of affordable housing and community development following the screening reinforced the message that relationships among audacious and persistent leaders with good ideas matter. Yet discussants stressed that investing in those relationships may matter even more. Here are a few of their suggestions:

1. Broaden and Deepen Institutional Relationships: Place-based community initiatives require more than locating housing close to schools and other neighborhood services. In promising initiatives, institutional actors invest in the whole community in addition to their traditional target populations. As Nicolas Retsinas, senior lecturer at the Harvard Business School and former head of Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies suggested, schools may be too important to cater only to children; they can be educational and cultural centers for the entire community.

Investing in relationships among service providers also affords cross-fertilization of expertise. Educators, health practitioners, childcare providers, and job trainers can learn from and with one another in the spirit of the Progressive Era’s community school movement, as UEP and child development professor Fran Jacobs recalled.

2. Set Reasonable Expectations for the Partners: Aaron Gornstein, Undersecretary of the Massachusetts Department of Housing and Community Development and former executive director of Citizens’ Housing and Planning Association, cautioned that the imperative to collaborate can overburden systems that are already stretched to the maximum. Affordable housing providers have been charged with fighting poverty, promoting racial inclusion, practicing smart growth principles, and promoting energy efficiency. Adding education to their goals may be an unreasonable expectation. Similarly, schools can only do so much on top of their commitments to raising educational achievement. To scale up these comprehensive models, policymakers need to set reasonable expectations for what each partner might achieve and ensure adequate funding for expanded agendas.

3. Fortify the Partners by Engaging Additional Investors: One way to fortify the partners is to tap funding streams. Panelists recognized Massachusetts’ exemplary state-funded tenant- and project-based subsidies as vital supplements to the mosaic of federal resources. They also acknowledged the potential of combining the Department of Education’s Promise Neighborhoods and HUD’s Choice Neighborhoods, as the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative (DSNI) is pursuing in Boston’s Roxbury community. Given the diminishing appetite for public expenditure, local community foundations and corporations can be recruited as investors.

4. Cultivate Personal Relationships: Successful partnerships require investment in personal as well as institutional relationships. In response to a question about how he gets buy-in from notoriously beleaguered school administrations, Baron conveyed that he often sits down with the school superintendent to discuss needs and strategies even before meeting with the mayor.

Investing in personal relationships also means investing in residents. For example, May Louie, director of leadership and capacity building for DSNI, stressed that parents and extended family members are not only recipients of services; they are the “first teachers.” Early education and community health centers can engage these informal educators as participants and partners in programming. Louie also recommended shared equity homeownership and community land trusts as mechanisms for residents to be vested partners in neighborhood development.

Questions for Continuing the Conversation:

• How does investing in the entire population of well-designed and managed public housing developments (eg. the JobsPlus demonstration program) compare with mixed-income models that allocate units to new, higher-earning families?

• How can we foster relationships among residents with both similar and diverse economic, racial, and ethnic backgrounds so they can help one another become more powerful agents of change?

• How can the housing and community development field collaborate with new partners to generate economic and employment development that closes the gap between wages and affordable housing?

Comments