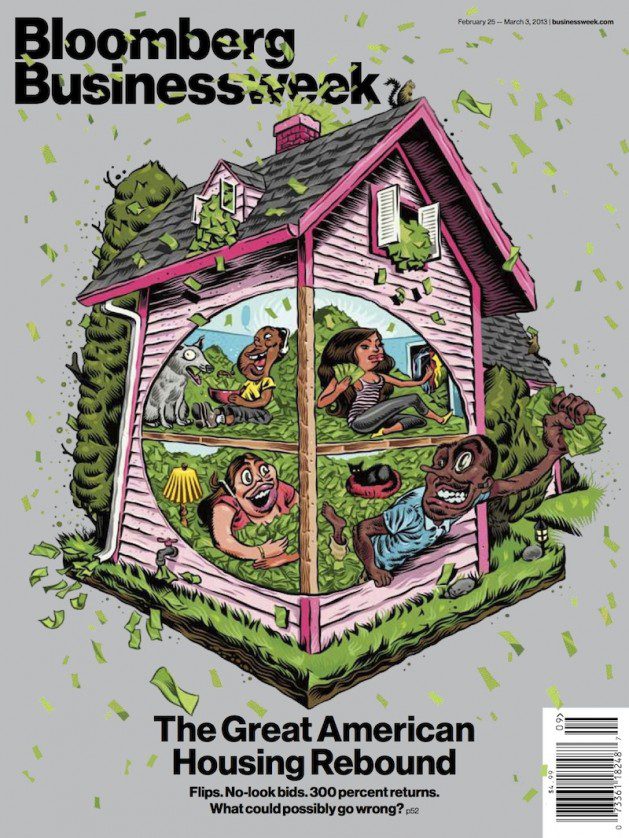

All the criticism that the recent BusinessWeek cover is getting is well deserved.

It deserves even more.

The juxtaposition with the relatively benign article inside especially makes one wonder why such smart people came up with such a racist illustration. Was it overt intent? Are they a bunch of secret white supremacists waiting for their opportunity to inject their poison? Or are they just expressing an “implicit racism,” a set of assumptions so ingrained in the American psyche that we don’t even notice that they’re there until something like this happens?

It’s easy to blame a handful of people for this. They see the error of their actions and they offer heartfelt apologies. Case closed.

But the case isn’t closed, and shouldn’t be.

The Kirwan Institute just released State of the Science Implicit Bias Review 2013, which they hope to update annually. This 102-page report teases out the forces that influence individual behaviors without our awareness and that no doubt contributed to the creation of BusinessWeek’s cover.

Sadly, implicit bias is everywhere and far more insidious than overt racism. But the good news is that a slow awareness about it is reaching a wider audience. In a recent note, the executive director of Kirwan, Sharon Davis, quotes from a recent column by conservative writer David Brooks:

Sometimes … behavioral research leads us to completely change how we think about an issue. For example, many of our anti-discrimination policies focus on finding the bad apples who are explicitly prejudiced. In fact, the serious discrimination is implicit, subtle and nearly universal. Both blacks and whites subtly try to get a white partner when asked to team up to do an intellectually difficult task. In computer shooting simulations, both black and white participants were more likely to think black figures were armed. In emergency rooms, whites are pervasively given stronger painkillers than blacks or Hispanics. Clearly, we should spend more effort rigging situations to reduce universal, unconscious racism.

And it is everywhere. In a New York Times op-ed, The Good, Racist People, Ta-Nehisi Coates writes about an incident at a deli near Columbia University. His favorite deli, one that he might go to a few times a day. Where good and kind people work. A month ago, he writes:

The actor Forest Whitaker was stopped in a Manhattan delicatessen by an employee. Whitaker is one of the pre-eminent actors of his generation… But the man who approached the Oscar winner at the deli last month was in no mood for autographs. The employee stopped Whitaker, accused him of shoplifting and then promptly frisked him. The act of self-deputization was futile. Whitaker had stolen nothing.

Coates goes on to say:

I am trying to imagine a white president forced to show his papers at a national news conference, and coming up blank. I am trying to a imagine a prominent white Harvard professor arrested for breaking into his own home, and coming up with nothing. I am trying to see Sean Penn or Nicolas Cage being frisked at an upscale deli, and I find myself laughing in the dark. It is worth considering the messaging here. It says to black kids: “Don’t leave home. They don’t want you around.” It is messaging propagated by moral people.

When something like the BusinessWeek cover happens, we need to express the moral outrage that is, in fact, being expressed. And we need to right the specific wrong. But we need to go further. We need to examine ourselves, our work, and our deepest assumptions. Ernesto Cortés Jr., the legendary organizer and director of the West/Southwest regional network of the Industrial Areas Foundation, once said that “awareness never changed anything.” But it is a place to start.

Comments