To achieve racial and economic inclusion, she says, we must focus our energy and resources on those who have been left behind — both people and the places they live.

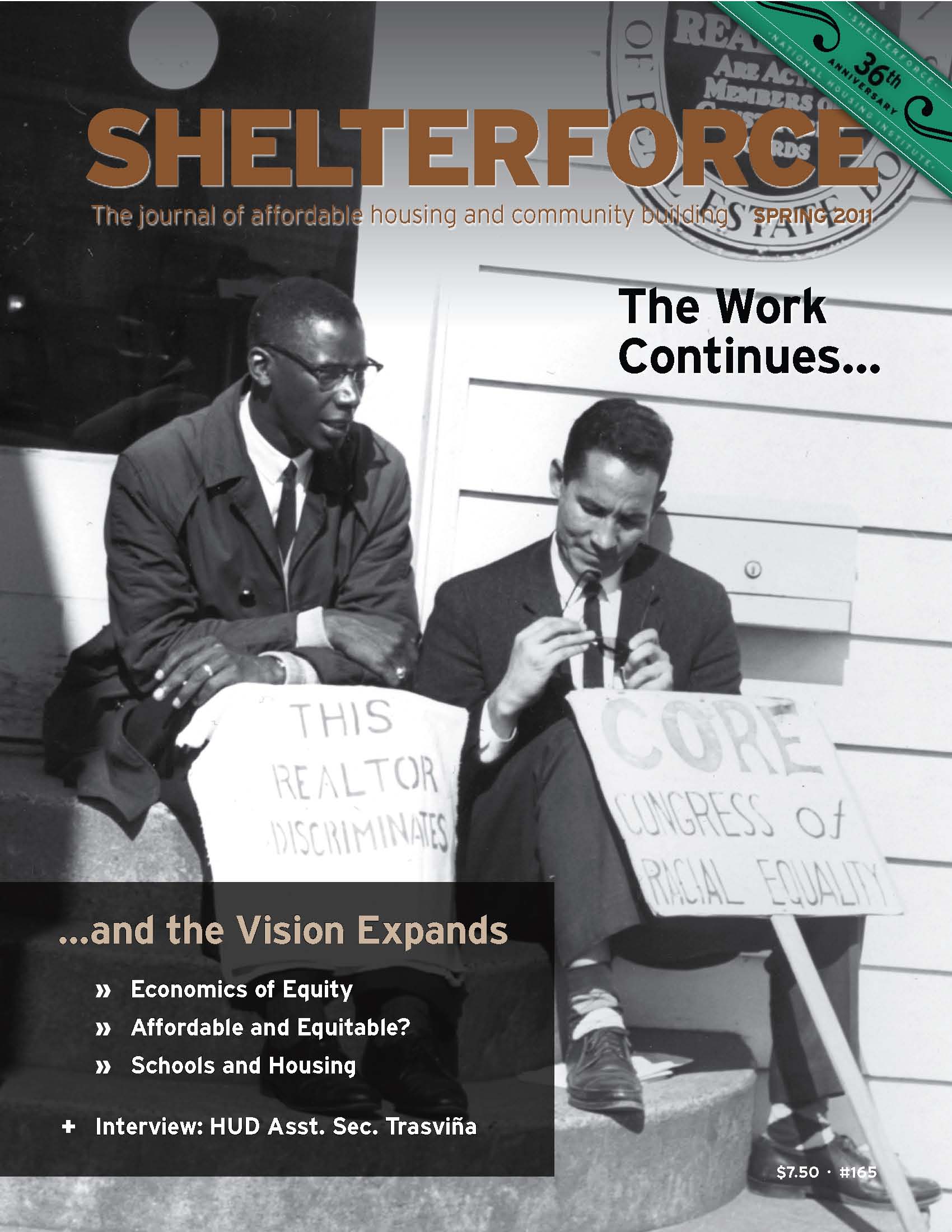

This is, of course, what the community development movement does. In this issue we remember that one of the primary victories of the civil rights movement, which birthed the community development movement, was the recognition that separate is not equal.

Improving communities where low-income people and people of color are concentrated, and effectively still segregated, is in many ways the bread and butter of the current community development field. But we need to remember that it is only one side of the coin. To be true to both our roots and our vision, we also have to continue to fight for equal access to existing opportunity.

HUD Assistant Secretary for Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity John Trasviña, while he focuses on strengthening fair housing rules and enforcement in our interview with him, talks about both sides of that coin when he mentions the challenges of balancing ability to stay in place and to move to opportunity in the Choice Neighborhoods program.

Following in that theme of balance, Phil Tegeler of the Poverty & Race Research Action Council and Scott Bernstein of the Center for Neighborhood Technology discuss how to balance the advantages of location efficiency with the other costs/benefits of high-poverty vs. low-poverty locations. Tegeler argues that we can’t look just at transportation costs or we run the risk of reconcentrating poverty; Bernstein says location efficiency and opportunity line up better than you might think.

Also on our fair housing theme, Heather Schwartz reports on how inclusionary housing improves education outcomes, and in Shelter Shorts, we report on the National Community Reinvestment Coalition’s lawsuit against dozens of FHA lenders and on new coalitions for bank accountability, some of the latest fronts in the fight for fair and inclusive lending.

Unfortunately, the federal austerity budgets currently on the table — both the president’s and the Republicans’ alternatives, though to markedly different degrees — offer the opposite of a focus on those left behind. Despite the president’s assertion that the budget should not be balanced on the backs of the poor, essential programs that see those left behind through hard times — the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program, homelessness prevention, higher education assistance — are being cut, while Bush-era tax cuts for the wealthy and corporations, massive spending on foreign conflicts, and such obviously non-productive deficit-boosters as a mortgage interest deduction for vacation homes have been retained.

Closer to (everyone’s) home, municipal budgets are suffering even more dramatically than the federal one. Especially hard hit are the cities that have themselves been “left behind” — having lost so much population since their peak days as manufacturing hubs that they are now having to come to terms with entirely new visions of themselves and their neighborhoods, as Deborah Popper and Frank Popper describe. This new framework requires community developers in those cities to rethink their roles and even their missions. Alan Mallach explores some of how that’s happening in Youngstown, Cleveland, and Detroit.

There’s little that’s less fair than those with vast amounts of cash treating people’s homes as disposable chips in a financial gamble, flouting codes put in place to ensure basic decency and safety when their profits are threatened, and then walking away. But that’s exactly what’s happening to many large apartment buildings in New York City and other markets. Dina Levy and James Fergusson show us how this less-reported aspect of the foreclosure crisis is playing out — and how tenants are fighting back.

Even in a time of divisive politics and financial woes, it’s important to keep our eyes on the prize — fair treatment and equal access to opportunity for everyone.

Comments