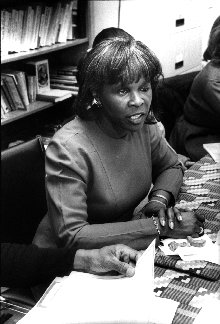

Willie Mae Gaskin

Part II: Collaborating for Change

(Click here for Part 1: New Partnerships)

Willie Mae Gaskin can’t walk through the halls of the Warren/Conner Development Coalition (WCDC) on the Eastside of Detroit without being stopped by nearly everyone she passes. There are meetings to schedule, issues to discuss, and congratulations to be offered, following her grandson’s wedding just a few days ago.

A volunteer for only a few years, Gaskin seems to know everyone and be involved with everything.”We’ve got an office with a desk and a phone for you whenever you want it, Miss Gaskin,” teases one staffer. Gaskin smiles. “I just might need it one of these days.”But it’s hard to picture her behind a desk. She’s only stopped by the office briefly this morning, long enough to pick up fliers about an upcoming meeting, which she’ll put under the doors of every house on her block, and to sit and talk a bit about her involvement in the community’s latest resident-led revitalization effort. It’s a big project, she admits.

There are lots of issues to deal with in this community of 75,000. The housing stock is decaying, the economic base is weak, and funding for human services is being cut while the needs of residents are increasing. Projects to tackle these issues have helped somewhat, but without a holistic approach it’s hard to see how the neighborhood can find its way out of the mess it’s in. That takes vision. It takes resources. But most importantly, it takes an understanding among neighborhood residents that everything is linked, and that their participation is needed in the effort to rebuild their community.

And people don’t usually see the connections between all of those issues, Gaskin says. “It’s not hard for me to see the connections,” she adds, “because of what I’ve been doing my whole life – raising a family. “Then she’s off, fliers under her arm.

CCIs: A New Model

Gaskin and WCDC are part of the Rebuilding Communities Initiative (RCI), a seven-year venture by the Annie E. Casey Foundation (AECF) to assist low-income communities in five cities through a resident-led process of neighborhood transformation. RCI, in turn, is one of a growing number of similar foundation-funded comprehensive community initiatives (CCIs) throughout the country.

Evolved from various community development models, CCIs work to strengthen the capacity of participating organizations and neighborhood residents to address a wide range of issues and bring about change. These initiatives focus on building leadership among local residents and organizations and require collaboration among a wide spectrum of neighborhood residents and institutions.

Working comprehensively has been a stumbling block for many neighborhoods involved in CCIs, as the number of issues with which they must grapple often seems insurmountable. Learning to collaborate with a diverse range of community members has also been challenging for many participants, as has establishing governance structures to lead these initiatives. In struggling with these issues, foundations and neighborhoods have learned valuable lessons that can help inform and strengthen both CCIs and other revitalization efforts.

Comprehensive Planning

CCIs require community groups and residents to consider the links between issues that shape the community, and to plan accordingly. This is no easy task. Despite growing assertions that, to be sustainable, community development must encompass a broad range of issues, successful comprehensive planning has long eluded professional planners and government agencies. Resident-driven initiatives such as CCIs, though, are perhaps a better vehicle for this type of work. Residents are often better able to see the connections between issues, because, as Wanda Mial of the RCI site in Philadelphia’s Germantown neighborhood put it, “they live them every day.”

Willie Mae Gaskin, who sits on the governing board of the RCI project in Detroit, likens RCI to raising a family. “The community is all of ours,” she says, and every part of the community is part of everybody’s day-to-day life. “The schools, the stores, the parks – if you don’t treat them right, you hurt yourself.” It’s not so much about meetings and process and planning, she says. It’s a way of thinking in terms of day-to-day neighborhood life.

And it’s not about complicated concepts or bureaucratic language, either, she says. It’s about common sense. “I see people who live right next to boarded houses who mow their lawns right up to the edge of that yard. Why don’t they just mow the next yard too?” she wonders. “It’s like a big puzzle, and everyone has a little piece to do.” Initiatives like RCI, she says, seem to be a good way to assemble the pieces.

It’s not really that simple, of course. A focus on comprehensiveness leaves an initiative wide open for conflict and disagreement, points out Tonya Allen, director of the RCI initiative in Detroit. Participants are not always going to agree on issues to pursue, strategies, or goals, she says.

Cornelia Swinson of Germantown Settlement, the organization chosen to lead Philadelphia’s RCI site, recalls that from the very beginning, local residents told her, “I’m not interested in ‘those’ issues, I’ll just work with the project on my issue.” Particularly in a neighborhood as diverse as Germantown, she says, the common ground might not be all that obvious. Advocates of historic preservation in the neighborhood weren’t interested in dealing with issues like education, for example. But there is room for, and a need for, just about anybody within an initiative as broad and complex as this one, Swinson says. Above all, she continues, “integrating all of these issues is not scientific.” In fact, she says, this approach is often not really about the issues, but about a philosophy of building strength and capacity, which is what community development and self empowerment are all about.

The impetus for RCI came from work the foundation had done in trying to change state-level systems that dealt with families and children, explains Garland Yates, AECF’s program associate for RCI. “We realized that communities needed to be ready for the proposed reforms we were pushing, especially since community-based institutions were the entry point for reforms,” he says. This initiative was a logical next step in that it “changes how the big systems relate to communities’ needs, and deals with how to empower communities to define what they need.”

Yates believes that a comprehensive, integrated approach to community development is not a new concept, but was actually the norm until foundations and government began, in the late 1960s, to primarily fund only specific projects – housing, human services, or economic development. This led to the atomization of various community development efforts, according to Yates, and to the current predominant trend of community-based organizations letting the funding streams determine their agendas.

“Through this initiative I’m even more convinced of how dysfunctional it is to separate human services and physical development,” Yates says. “We need to combine all of the approaches we’ve been doing in community development to tackle these problems that these neighborhoods face.”

Most of the organizations leading RCI in the five participating neighborhoods had primarily focused on bricks-and-mortar development (i.e. housing, economic development) prior to joining the initiative. Involvement in RCI meant integrating human services, outreach, and community organizing into their missions.

The Ford Foundation’s Neighborhood and Family Initiative (NFI) began in much the same way. “We had been funding the community development field for 30 years,” explains NFI Program Associate Ruth Román, “and we wanted to bring together lessons we had learned. Some of those lessons were about fragmentation of anti-poverty programs. NFI was a way to examine how we could address them from a more comprehensive grassroots approach.”

Michael Bangser, executive director of the Hartford Foundation for Public Giving, an NFI participant, cautions that while the concept of comprehensive community development is a wonderful ambition, “we have to be careful not to drown community-based organizations with ambitious goals amid limited resources.” Funders have to be very careful to align the resources with the rhetoric of the project, he says.

Angela Wilson, the Detroit Mayor’s Office representative on the RCI site’s steering committee, similarly recalls that the comprehensive nature of the planning phase was daunting, and “overly optimistic.”

“We could have been more effective with more focus,” she feels, though she adds that the foundation, satisfied that the neighborhood has taken a broad range of issues into consideration, is now encouraging an approach more focused on a handful of topics.

System Thinking

Community groups involved in CCIs must also confront the challenge of sustaining such an ambitious effort. As much as CCI participants strive to capture the breadth of the issues in their neighborhoods, they also must grapple with the depth of the problems, and the causes rather than just the symptoms, in order to ensure that the effects of the initiative are long-lived. AECF refers to this element of a plan as “systems reform” – a shift in the way communities interact with the systems, agencies, and individuals that affect the neighborhood, to make them more responsive to the individuals who count on their support.

That’s no small task, says Swinson, because the initiatives are, by nature, operating on a very small scale – one neighborhood – while these systems are often citywide, statewide, or even national. “We can’t deal with the Department of Human Services without dealing with how they serve the whole city,” she says, “and then we would have to deal with the unions, which represent the social service workers.”

“There’s an inherent contradiction in the design of this initiative,” says Maggie DeSantis of Detroit RCI. “A very small area of focus, with very big goals.” For the Detroit initiative, systems reform became less an issue of changing service delivery, but more an organizing strategy. This strategy aims to strengthen residents’ capacity to the point where they feel they have the power to affect how services are delivered to the community.

Another RCI lead organization, the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative (DSNI) in Boston, saw systems reform as creating a plan for the neighborhood based more on guidelines for what the community wanted, rather than particular steps. “Being comprehensive means that the vision comes first,” says May Louie, RCI director for the site, “and then projects have to fit into those standards.”

|

“We wouldn’t say ‘We don’t want a McDonalds in the neighborhood,'” she explains, but the group might oppose a McDonalds that didn’t adhere to a resident-drafted plan calling for businesses that primarily support the local economy or don’t require parking lots fronting the street, for example.

The ability to see the big picture in a neighborhood often comes from unexpected sources, Louie said. When adult residents of the neighborhood were surveyed as to what they wanted the initiative to focus on for youth, they specified programs to help with college applications and SAT studying. When the youth were asked, though, the first thing they said was that they wanted economic power for their parents so they could work just one job and be home more often to spend time with them.

“Wow,” Louie recalls thinking. “These kids can system think!”

This type of thinking – seeing the neighborhood as an entire system rather than just a bundle of issues – is often a learning experience. Residents sometimes aren’t even aware of the issues that affect them, Louie points out. Many Dudley Street residents didn’t feel that the environment was an important issue for RCI to address, but they did want to include health issues. When a discussion made apparent the links between their health concerns and environmental issues, however, the group quickly included the environment as part of their plan.

The Boston RCI site also defines systems change in its own way. “It’s about finding the points of leverage where we can control basic needs, like food or energy,” says Louie, “even if it just means saving money and keeping that capital in the community, it makes a difference.”

The stumbling block to seeing the connections between issues often lies in thinking about them too hard, some of the sites have discovered, and in focusing on policy rather than on the day-to-day issues of people who use community services. Recognizing this, some sites have devised creative ways to get around these blocks.

DSNI executive director, Greg Watson, for example, wrote a one-act play based on what residents had said during a “visioning” process about what they wanted the neighborhood to eventually look like. The play – performed in the three languages spoken in the neighborhood – was able to convey the connections among the ideas of various residents.

The RCI site in Denver developed a role-playing exercise in which a staff member played the part of a resident who needed just about every service imaginable. While this example was extreme, it allowed participants to see that many of the issues affecting this hypothetical person were similar and could be dealt with in an integrated way.

Throughout the CCI process, Yates says, the neighborhood groups have to keep in mind that these initiatives are ultimately supposed to be about changing power structures and alleviating poverty. Many of the initiatives have gotten away from that, he says. “Most of them try to focus on what programs will solve the problems, without taking institutional barriers like race and class into account.” Changing systems and power structures requires something substantially more than a programmatic focus, he says, or the initiative will be short lived.

Collaborating is Key

Just as CCIs emphasize inclusion of a broad range of issues, the process also demands inclusion of a wide range of community participants.

Darryl Jordan, neighborhood development director for WCDC, the Detroit RCI site’s lead organization, says that establishing the initiative as a separate entity went a long way in allowing for collaboration in the neighborhood. “WCDC has baggage,” he says, “and it’s not always clear to the community what good we have done. That perception – even if it’s not a real problem – is bad enough. RCI allowed us to operate not as WCDC, but as RCI, and collaborate with organizations who otherwise might not have been willing to work together.”

Before the RCI initiative took hold in Denver, “the politics of the West Side were infamous,” recalls Pat Virgil, Executive Director of GANAS, a neighborhood human service organization and participant in the initiative. “There was lots more competition rather than collaboration. Lots of volatile relations and petty politics. This was disastrous and destructive.” Thanks to RCI, though, “people and organizations are maturing to the point where they realize that we’re all in the same boat, can agree to disagree, and can collaborate.”

It’s not the money that has drawn the organizations together, says Virgil, because what funds do exist make up just a small part of his organization’s budget. It’s the “spirit of collaboration” that makes the time and effort worthwhile, he says. “This is the most significant movement in the history of this community.”

“The groups realize that the need for collaborating is kind of like joining a union,” says Rick Manzenares, former chair of Denver’s initiative. “We’re now tight enough that if anyone came after us, we would support each other.” Groups have also learned that collaboration means more leverage when it comes to funding, and that the connections made through this initiative will last longer than the project itself.

When a new Texaco gas station/convenience store applied for a liquor license, Denver’s RCI lead organization worked out an arrangement with the store’s management by which Texaco would not sell alcohol and the group would help publicize the store’s opening. What could have been approached in a confrontational way was instead handled in a constructive and productive manner, says LeRoy Lemos, right, staff member for Denver RCI. The result was a stronger relationship and benefits for both the community and the new store. “An ounce of prevention,” explains Lemos, “went a long way.”

When a new Texaco gas station/convenience store applied for a liquor license, Denver’s RCI lead organization worked out an arrangement with the store’s management by which Texaco would not sell alcohol and the group would help publicize the store’s opening. What could have been approached in a confrontational way was instead handled in a constructive and productive manner, says LeRoy Lemos (right), staff member for Denver RCI. The result was a stronger relationship and benefits for both the community and the new store. “An ounce of prevention,” explains Lemos, “went a long way.”

“It’s a timing issue,” says Mustapha Abdul-Salaam, executive director of the Upper Albany Neighborhood Collaborative, an NFI participant in Hartford, Connecticut. “Fifteen years ago people wouldn’t collaborate because there were plenty of funds out there. Now people collaborate because they understand that the game has changed, and that if you’re going to survive, funding goes more to these types of collaboratives.” Funding isn’t the only reason to collaborate, he adds. “The problems are too significant [for individual groups] to be out there independently.”All it takes is one individual or organization to initiate a collaborative effort, as the Denver RCI site learned.

A new Texaco gas station/convenience store being built in the neighborhood had applied for a liquor license, which NEWSED feared would contribute further to the problems of alcoholism and easy access to alcohol in the neighborhood. A group of residents came together to discuss strategies, and decided to sit down with Texaco management to discuss their concerns.

After a number of meetings, the two sides worked out an agreement. The local Texaco management agreed not to sell alcohol in their new store, and also promised to work with the neighborhood to hire from within the community. For their part, the neighborhood group agreed to help publicize the store’s opening.

What could have been approached in a confrontational way was instead handled in a constructive and productive manner, says LeRoy Lemos, staff member for Denver RCI. Rather than setting up an adversarial situation, which would have created a tension-filled relationship, the result was a stronger relationship and benefits for both the community and the new store. “An ounce of prevention,” explains Lemos, “went a long way.”

Governance and Lead Organizations

For a community taking on the challenge of collaborating through a CCI, one of the first tasks is establishing a structure to govern the initiative. No single model will work in every neighborhood, so the sponsoring foundations often leave communities to figure out how to handle the delicate issues of sharing power, encouraging participation, determining representation, and executing projects. The relationship between the lead organization and the governance of the initiative has to straddle the fine line between leadership and control.

Germantown Settlement decided to establish a new organization to govern RCI in the neighborhood. This organization, the Lower Germantown Rebuilding Community Project, takes its leadership from the Germantown Community Collaborative Board (GCCB), a body elected by neighborhood residents. Though Germantown Settlement acts as the fiscal agent, provides overhead and staff support, and serves in a facilitating and coordinating role – at least through the early years of the initiative – it intends for the new governing organization to become entirely independent and to set the initiative’s agenda.

Emanuel Freeman, Germantown Settlement’s president and CEO, sees the new board as a resident-driven power structure through which eventually all major neighborhood decisions will pass. “GCCB will set expectations for everyone in the community,” he says, “even Germantown Settlement.

“The decision to create a new entity entailed a great deal of work – more than integrating the initiative into Germantown Settlement would have, according to Freeman. The process opened doors for all kinds of potential new conflicts, he says, such as competition between organizations for funding and other types of support, and potential differences in philosophies and strategies.

Freeman says that Germantown Settlement, like all community organizations, has years of history and reputation behind it, which can be a weakness as well as a strength. Freeman, who has been with Germantown Settlement for more than 25 years, also recognizes the active effort he must make to not direct the initiative. While his leadership has been a significant part of the neighborhood’s successes, such a leader has the potential to supplant real participation. Freeman says he hands off as much leadership to the staff members and board as possible and makes an effort to speak last during discussions at board meetings. “I don’t want to drive groups away,” he says. “Sometimes it’s better for me not to be there.”

For the initiative to work, continues Freeman, Germantown Settlement has to be willing to submit itself to a system of accountability driven by residents. “We’re risking building something new,” he says. “It could end up being our own competition. But it’s easier to build ownership in an organization created by the community.”

Residents hold a majority on the GCCB board, created through a yearlong process of town meetings and elections. The elections attracted a wide range of candidates, both established community leaders and residents new to working with the community. Some seats were contested, and residents took their candidacies seriously, distributing fliers, meeting people, and convincing people to vote, according to Cornelia Swinson, Germantown Settlement’s vice president for planning and development, and the neighborhood’s first RCI director. Though the highest turnout in any of the neighborhood’s five geographic sectors was just 121 votes, Swinson says that such a turnout is “very good, in the context of the usual level of apathy.” The neighborhood elected 37 residents and institutional representatives to the board.

Despite Germantown Settlement’s efforts to be inclusive in establishing GCCB, some residents and neighborhood organizations have refused to participate in the RCI process because they feel Germantown Settlement has been gathering too much power in the neighborhood.Swinson attributes some of the opposition to the structure of Germantown RCI to the plan’s shifting of power to residents and away from some of the neighborhood’s “old-style” leaders involved in Philadelphia’s entrenched ward politics system. According to Swinson, some of the newly elected board members were expecting traditional political game playing in the new organization, but residents who were new to the process quickly took over, establishing ground rules and bylaws that ensured that it would be difficult for one person or group to dominate the process. Board members who were there strictly to advance their own agendas quickly saw that theirs would be a losing cause within the organization, Swinson says, and eventually stopped coming to meetings. Swinson adds that even some community group leaders, who had become “de facto leaders” because they took up an issue and championed it, were unwilling to participate because the new system held them accountable to residents and demanded that they discuss issues openly.

Other residents have a different take on the situation. “Germantown Settlement had its own idea about what it wanted to have happen,” says Sheila Laney, president and one of the founders of the Block Captains Association in Germantown, “and that script was already written before the elections were held.” Laney adds, “A corporate structure can never empower anybody but themselves, and that’s what they have.

“Germantown Settlement holds four seats on the board, while no other organization has more than one. Though Freeman, who holds one of those seats, is quick to point out that four seats is not enough to control decisions, Laney says those four seats alone don’t represent the organization’s control over the initiative. According to Laney, many of the other board members are within Germantown Settlement’s “spheres of influence.” They have been involved with the organization in some way or another over the years and generally defer to that group, she says.

Michael Parente, chair of Germantown’s West Side Neighborhood Council, echoes Laney’s feeling that Germantown Settlement dominates the RCI process, though he objects to some aspects of its structure for different reasons. He expresses concern that Germantown Settlement’s focus on poor communities results in a failure to include individuals and organizations that do have equity or capital in the community. Such people or groups don’t have adequate representation on the boards of Germantown Settlement or GCCB, he says.

“One reason for many of these problems, Parente says, is that Germantown Settlement staff works on RCI for a living, while most community residents work in other occupations during the day. “Those of us who are involved as neighbors don’t have the time to put in, and while we’re all off at work in between meetings, the organization is rolling right along with their own ideas. The process was taking place in the absence of the community, and was tightly controlled by Germantown Settlement.” While there were times he felt he was influencing the process, Parente recalls more often feeling that “we were being handed what was going to happen and were just along for the ride. In meetings it would seem like things were settled, and then by the next meeting those actions would have gone in another direction. I don’t think it was malicious, but in between meetings the staff just had other ideas. They might very well have been better ideas, but still, what’s the point of participating, then?”

Kathy Brown, [see profile] a resident representative on the GCCB board, stresses that there were no preconceived notions about how the RCI process would work. “There was no outline, we kind of felt our way through it and learned as we went.” Brown says Germantown Settlement is a strong community organization that had all of its components in place and could handle a grant that size. “What other group in the neighborhood could be that responsible?” she asks. “It has gotten complicated with other groups, but any time you’re dealing with money that’s how it is.”

The Denver RCI site, led by NEWSED, also ran into difficulties with some residents who objected to the initiative’s governance structure. The 31-member advisory council and 12 committees that govern the initiative are open to local organizations’ staff as well as community residents. According to NEWSED’s Executive Director Veronica Barela, a group of residents disrupted the RCI process by insisting that the steering committee consist only of people who lived in the neighborhood – not neighborhood groups, and particularly not NEWSED.

Denver City Council member Deborah Ortega recalls that period of Denver’s RCI project differently. “The perception in the community was that NEWSED wasn’t being inclusive,” she says, “so a group of residents began raising questions. People were just trying to raise some of those concerns, and make NEWSED and the [Casey] foundation accountable to the community.”

The Denver and Philadelphia RCI sites illustrate well the point that perception is as important as practice in these initiatives. The beginning of a new initiative doesn’t wipe the slate clear of past neighborhood politics – in fact it can exacerbate them. Since the success of these initiatives depends on active participation by a wide range of individuals and groups from disparate backgrounds, the organizations leading the early stages of these projects need to be attentive to establishing agendas and processes that satisfy the needs of all those involved.

One of the toughest balancing acts for CCIs at the local level is between building a community and building a community organization, says Swinson of GCCB. The dilemma of RCI lead organizations, she says, is that while “an initiative that has this kind of importance can create division within organizations,” GCCB board members are expected to contribute whatever resources they and their organizations can offer. Germantown Settlement brings strong organizational and leadership skills, and so should be expected to contribute those resources. Swinson adds that RCI’s goals include building capacity within the lead organization as well as the neighborhood. “It can’t be that the investment of the opportunity results in outside change but none within the organization.”

To not allow RCI to benefit from Germantown Settlement’s skills would only hurt the process, Freeman says, but tapping into those resources should come at the behest of the board. And he takes that a step further, saying that Germantown Settlement needs to constantly check itself against the work of GCCB’s initiative. “We need to look at internal operations and ensure that there aren’t contradictions between what we practice and what we preach.”

Another Approach to Governance

DSNI in Boston chose a different route in creating its governance structure and integrated RCI into the existing organization. The group used RCI resources to strengthen its board by making it more responsible to community residents and ensuring that its makeup reflected the community’s.

RCI allowed DSNI to focus on engaging groups who hadn’t been very involved in community projects in the past, says Al Lovata, a member of the DSNI board. “We made it a priority to engage more youth, as well as more members of the Latino and Cape Verdean communities,” he says. RCI also allowed DSNI to refocus its goals and adjust to its enhanced role in the community. Prior to RCI, Lovata said, DSNI was “drifting.”

Garland Yates, AECF’s program associate for RCI, says the foundation was skeptical when DSNI proposed this governance plan. “We hadn’t encouraged this because we were calling for a governance entity that balanced out a multitude of interests, and most groups would likely say they can’t meet that standard,” he says. “Existing organizations have their own culture, history, and mission, and this initiative is meant to guide an entire neighborhood, including the lead organization. How can the initiative have oversight of the lead organization if it is a subset of that group?” But DSNI prevailed, the initiative has progressed, and Yates feels the correct decision was made.

In hindsight, Maggie DeSantis of the Detroit RCI site wishes her group had taken the same route and incorporated governance of the initiative into her organization. She, like Freeman in Germantown, says that establishing a separate board, with entirely new leadership and structure, took a great deal of time and energy. There are advantages to the separate structure though, she admits, in that the RCI board is able to focus solely on the projects that are part of the initiative, without getting bogged down in the minutiae of running the entire organization.

The local project’s new steering committee, however, was slow to take on the role of leadership, recalls Angela Wilson, who represents the Detroit mayor’s office on the RCI board. “Early on I tried to stay back and not run or steer the initiative, for fear of manipulating the process from the mayor’s office,” she says, “but then I realized I wasn’t playing the role I should have been, bringing information and access to the table.” In fact, adds Wilson, the entire steering committee at first was not taking action at all, but was just entrusting the staff to run the initiative. When AECF staff visited and saw that this was the case, she says, they insisted that the committee play a more active role in operating the initiative. This modification, which was implemented immediately, has changed the initiative for the better, Wilson says, since each member of the committee is taking ownership and responsibility for the process.

That was an important lesson for the steering committee, Wilson says. “Groups running these projects need to take their role very, very seriously from day one, know the goals and plans, and own them,” she says. “Ours was drafted by the staff [of WCDC] and we didn’t own it.”

Tonya Allen, who staffs the Detroit initiative, recalls the change in much the same way. “We were coming at the initiative as the lead organization, not as RCI. This caused conflict, and it disempowered the steering committee and the whole project,” she says. After a visit from a technical assistance consultant, committee members began asking questions and realized the initiative wasn’t happening as they wanted it to. This realization, she says, changed the way the committee thought about the project and allowed them to take ownership of the initiative.

Tom Burns, director of the Organizational Management Group (OMG) Center for Collaborative Learning, which has been evaluating RCI, suggests that this approach – creating a new entity to govern local initiatives – is the better path for lead organizations. “Building a new group is easier than figuring out what it would mean to re-think their own board” to comply with RCI requirements, he says.

Burns does, however, recognize the challenges of the path Germantown and others have taken. “Going for a democratic structure is very innovative,” he says, and Germantown Settlement may not have realized how ambitious and difficult that strategy was when it began.

New organizations also grew from the Ford Foundation’s Neighborhood and Family Initiative, which channeled funding to local groups through community foundations. Most of these groups of residents and neighborhood stakeholders subsequently decided to incorporate as independent organizations to lead the local initiatives.

Using local foundations as intermediaries “makes sense” but raises potential problems as well, says Abdul-Salaam, of the NFI site in Hartford. The neighborhoods that are part of these initiatives are traditionally disenfranchised, he points out, and foundations are often part of the structure that has ignored them. “The [local] foundation is leery because these initiatives are about changing the status quo,” he says.

Michael Bangser, executive director the Hartford Foundation for Public Giving, the intermediary in the Hartford NFI site, admits that in selecting the initial board for the local initiative, his foundation chose people it knew, people connected with neighborhood institutions. “It takes a few years to penetrate the community and get people involved who might not have previously come to the attention of the foundation,” he says, adding that having those people’s participation is important. “The assumption was made that by putting together a collaborative we would quickly and automatically get a clear sense of what residents want. We learned that we shouldn’t assume that the board knows the needs of the residents.”

Struggling with Participation

As the organizations leading CCIs begin to move beyond establishing a structure, the issue of sustaining resident participation becomes even more complicated. As with any community-based initiative, CCIs depend heavily on the participation of many individuals with a wide range of connections to the neighborhood. Rooted in the belief that the more people are involved, the more likely the initiative is to succeed in the long run, these initiatives – in principle, at least – aim to include residents from all parts of the community and tap into their skills, resources, and knowledge. This can be particularly challenging in an initiative that lasts many years and rarely produces tangible results right away.

“People have to accept that this is going to take time,” says Geoff Canada, executive director of the Rheedlen Center for Children and Families, a site participating in the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation’s Neighborhood Partners Initiative. “If you say you expect to see changes in a year or two, people will get disappointed. Winning isn’t the goal in the first year, it’s really knowing the problem. You need that perspective, you need to do your homework first and then you can make the difference.”

“We try to involve people in the issues…in their day-to-day life, to appeal to their self interest. Parents with kids get involved with schools, for example,” says Melanie Styles, program director for the Enterprise Foundation, which participates in a CCI in the Sandtown/Winchester neighborhood of Baltimore. Focus groups draw the largest number of participants into the process, she says, because they require only a small time commitment and give residents a chance to be heard on whatever issues they feel are important.

However, Styles says that as Community Building in Partnership, the new organization leading the Sandtown/Winchester initiative, grew, it “drifted into doing things rather than working to transform the neighborhood.” It’s easy to “lose focus about whether or not that will bring about the change that you really want to have happen at the end of the grant. We now realize that we need to refocus on community building.”

Bill Traynor, who coordinates technical assistance for RCI sites, similarly warns that “there’s too much of an assumption that you can micro-manage and push the process along.” He likens trying to see progress after just a few months to walking into an operating room in the middle of surgery. “You see guts lying on the table, and you wonder ‘is this progress or is it catastrophic?'” Residents have to be prepared for the difficulties and problems they are likely to encounter before seeing any results of the initiative, he says.

Evaluations of CCIs and of other community-building efforts refer to this difficult balance as the “product-process tension.” On the one hand, there are issues, some of crisis proportions, that need to be dealt with immediately – crime, deteriorating housing stock, etc. – and it’s tempting to use resources to fund “quick-fix” solutions to these problems. Seeing quick and easy results is satisfying in the short term, but once the money runs out, neighborhoods often still face the same problems.The alternative involves a process that engages residents in fashioning and implementing a long-term strategy to develop sustainable solutions to chronic neighborhood problems. But because, particularly in CCIs, this approach doesn’t produce significant results right away, obvious problems can actually worsen as initiatives progress, leaving many residents disenchanted with the project.

Sheila Laney of Germantown was involved in GCCB at the outset of the project but pulled out after becoming frustrated with what she says is an initiative that has had no impact, is controlled by Germantown Settlement, and is focused more on process than on product. “I was initially very excited about the concept of people taking an active role in their own uplifting,” says Laney, “but now I don’t see that really happening.”

“Capacity building is supposed to mean putting people in a position to change or make change,” Laney continues. “The capacity is going to come from people being more involved, not from more board meetings.” The initiative began with a series of focus groups, Laney recalls, which she participated in and felt were very productive and useful, because they focused on “what will it take to make our community the best.””Dismantling that was a mistake,” she says, “because then the focus turned to building the collaborative board rather than working on the issues. It became like a corporate board.

“What you get out of an initiative depends upon what you put into it, some say. “People have to do more than just come to the meetings,” says Kathy Brown, a Germantown resident on the GCCB board. “They have to commit to helping implement. The ones who come to meetings and don’t do anything will eventually stop coming. People get lost because if they’re not very into it, it’s hard to see that anything has been accomplished.

“You have to make sure that something positive, some sort of action, comes from every meeting,” Brown says, otherwise people who aren’t traditionally involved in neighborhood affairs won’t want to come and won’t be represented in the process.

“You need to constantly remind people what has been accomplished,” agrees May Louie of the Boston RCI site. The project may well be about transforming the neighborhood on a grand scale, she says, but what will excite people is what was accomplished today.

However creative a community may be when it comes to finding ways to encourage participation, none have been able to avoid the inevitable onslaught of meetings that comes with such a venture.

Michael Parente from Germantown says he was quite active in RCI during the early stages of the project, but decided to withdraw from the initiative because he was expending an enormous amount of energy and not getting very far. Parente says he quickly grew frustrated with the way the meetings and the process were dominating the initiative. “I feel quite relieved to not be involved,” he says. “I feel like I can accomplish more by going out with a can of paint to paint over graffiti on my block than I can by attending meetings.”

“That’s a shame,” he admits. “You need the meetings.”Anita Miller, program director of the Comprehensive Community Revitalization Program (CCRP), a CCI in the Bronx, says CCRP tried to avoid the trap of too much process. “We made sure to start implementing projects immediately, in order to build credibility and to start fixing the most obvious problems,” she says. She’s quick to add that showing results need not be at the expense of capacity building, or of creating an infrastructure through which community groups can continue the work after foundation funding for the initiative is depleted.

Community groups also have to be prepared for the fact that, once the balance is struck between process and product, not everyone is going to be satisfied. As CCIs develop, the realization of just how hard it is to reach consensus leads some participating organizations to depart from the “more is better” philosophy of resident participation.For example, after the planning phase of Denver’s RCI stalled for nine months due to some residents’ opposition to the board composition, the initiative’s steering committee finally said “this is how we’re doing it, either join us or let us do our work,” recalls Veronica Barela, NEWSED’s executive director. While the initiative didn’t want to shut anyone out, she says, this group was not willing to be productive. “The foundation has to realize that it is very difficult to embrace everyone in the community. It’s really not that much money, and people don’t realize that there are ways that it has to be spent, so troublemakers come out and try to control it. We had to develop a process, not just give out money.”

Dismissing groups and individuals who raise questions as “troublemakers” isn’t productive though, says Denver Council Member Deborah Ortega. Bringing together so many different people with so many different agendas is difficult, she admits, and conflicts should be expected, but “you need to separate out personality issues from valid concerns.”Though her district includes the neighborhood where NEWSED is implementing RCI, Ortega says she hasn’t been invited to participate since she stood by the residents raising these questions. A lead organization for an initiative like this, she says, “has to be completely open and not want to have total control of a program that is supposed to involve the entire community.”

Organizations often use the demographics of a community to demonstrate need and get dollars from funders, Ortega says. “This is one community that has had that done to it a lot, but money doesn’t filter down to the people in the neighborhood. The organization needs to do the job of reaching out to the community and seeing that the money goes to programs that will truly benefit people in the community.” People from all parts of the community need to be included in meaningful ways, she adds, not just to project the image of an inclusive process. “Lots has to do with how people feel, whether or not they feel truly valued. They need to feel like they’re being heard.”

“We need to get more resident input,” says Rick Manzenares, former chair of Denver’s initiative, “but we don’t need the whole community. We need to do things as well as make sure everyone has had a chance to talk about them. We need to figure out how to tap into people’s assets, get their time in ways that they want to give it, which may not necessarily be by attending meetings.”

Gaskin, Detroit’s omnipresent volunteer and a resident member of the RCI steering committee, comments on the difficulty of sharing ideas at meetings when a number of people are trying to voice their concerns at once. “I was brought up to let a person finish talking before you say something,” she says. “At these meetings you have to just jump in.” That kind of dynamic is difficult for her sometimes, though, and discussions will pass before her point is heard. Gaskin suggests that some residents could use some help in the basics of meetings, such as how to present suggestions.

Of the difficulties lead organizations face in cultivating participation, Yates of AECF says that while sites knew that RCI required resident engagement and a system of accountability to residents, “part of the problem was that there wasn’t a clear threshold of standards.” This was deliberate, he says, in order to give the sites maximum flexibility in their processes. That leaves no standard upon which to judge a group’s success or failure in the area of resident participation, and AECF staff reconciles that gap by basing evaluations on the sites’ own experience and standards. “If they use focus groups that’s good,” Yates says, “but the ongoing structure has to have representation. What I look for most is ‘are the people who use and depend on the services and programs being discussed as a part of their major support system involved in decision making?’ We need to get people involved who are not historically involved, but not just in a consultative way.”

Greg Watson of DSNI agrees. “Representativeness is more important than lots of people at a meeting,” he says.

Once organizations have determined their own level and form of resident participation, these efforts should attend to both the tangible results they produce and the process they create. If CCIs succeed in creating community ownership, the neighborhood will reap the benefits of this work long after initial projects are completed.

Staffing the Initiative

As much as a CCI depends on broad-based participation, it also depends on having strong staff to coordinate the initiative. The day-to-day management of scores of ideas, people, and projects requires constant attention. While volunteer boards may govern the initiative, paid staff are crucial to its ongoing progress.”So much was invested in the governance entity that no effort was put on operation capacity,” says Abdul-Salaam, the fifth executive director of the Upper Albany Neighborhood Collaborative in six years. “What you’re up against is communities that have been underdeveloped and underinvested, and there’s a curve they need to catch up to. That level of expertise may not be in the community itself,” he says, and staff need to be recruited to bring that value to the community.

“An initiative like this is very technically and professionally focused,” says Swinson of Germantown. “You need a staffer who can deal with that, who knows how to work with foundations and can quickly adapt to this kind of foundation relationship.”

“It’s an unpredictable job,” she continues. “You need intellectual skills, experience in community-based work, an understanding of and creative approach to politics in neighborhoods and in community organizations. You need to always know what everyone is doing.” As if to illustrate her point, Swinson, in the course of a discussion, recalls meetings from over two years ago, who attended, and what was discussed.

“It’s an evolving position,” says Mial, who staffed the Germantown initiative for close to two years. “It’s a balancing act, and you need to be able to contend with a constantly changing landscape.” While staff members are responsible for overseeing an initiative’s capacity building efforts, she adds, they also have to implement steps of the initiative without taking control away from the residents.

“These [initiatives] are conflict-ridden,” says Mial. “CCIs are not for the faint of heart. Staff had better be ready for that.”

CCIs: Challenges and Opportunities

As CCIs move into maturity, they are grappling with some of the same issues their predecessors in community development faced, along with some new ones. While most community-based organizations are searching for new ways to encourage and sustain participation, the length and complexity of CCIs makes this more difficult. And neighborhood groups have long experimented with different governance structures, but few have had to encompass as many different organizations and segments of the community as CCIs demand. Developing comprehensive strategies is not necessarily a new concept, but remains an elusive goal for neighborhoods in which tackling a single issue can be enough to overwhelm a community organization.

In the end, there remains no single method or solution that best suits all neighborhoods undertaking such efforts. CCIs aim to give neighborhoods the tools to actively pursue their own solution to this puzzle.

As Cornelia Swinson of the Philadelphia RCI site says, there’s no science to these initiatives, nor is the focus about issues like economic development, crime, or even housing. It’s about how a neighborhood integrates and manages those issues, and it’s about building and maintaining relationships to transform the way a community works. It’s about finding sustainable solutions to problems of chronic poverty, neglect and disenfranchisment by developing the capacity of the neighborhood’s most valuable resources – the skills and strength of those who call it home.

Accompanying articles to this report:

Preparing for Change

Increasing Meeting Turnout

Words, not Whacks

The Rebuilding Communities Initiative

Profile of a Community Builder: Kathy Brown

Power and Race in CCIs

The November/December issue of Shelterforce included part one of this series, which examined the changing relationships brought about by CCIs, most notably those between neighborhood groups, funders, and technical assistance providers. This article series was supported with a grant from the Annie E. Casey Foundation. For more information about the AECF Rebuilding Communities Initiative, contact the foundation at: 70 St. Paul St., Baltimore, MD 21202; 410-547-6600; https://www.aecf.org

Editor’s Note, 2021: Shelterforce revisited this story to see if or how things have changed since it was written. Find out what we learned here.

Before the RCI initiative took hold in Denver, “the politics of the West Side were infamous,” recalls Pat Virgil (right), executive director of GANAS, a neighborhood human service organization and participant in the initiative. But thanks to RCI, Virgil says, people and organizations can agree to disagree, and can collaborate. “This is the most significant movement in the history of this community,” he says. |

“Integrating all of these issues is not scientific,” says Cornelia Swinson. In fact, she says, this approach is often not really about the issues, but about a philosophy of building strength and capacity which is what community development and self empowerment are all about. |

Comments