Joe Shuldiner has a very big job on his hands. As HUD Assistant Secretary for Public and Indian Housing, Shuldiner shares responsibility with over three thousand local housing authorities for the well-being of more than 800,000 families and the disposition of over 1.3 million housing units.

While many of these units provide decent and safe housing for poor and low-income families, all too many have become havens for the society’s worst horrors – drug wars, random violence and generation after generation of hopelessness and despair.

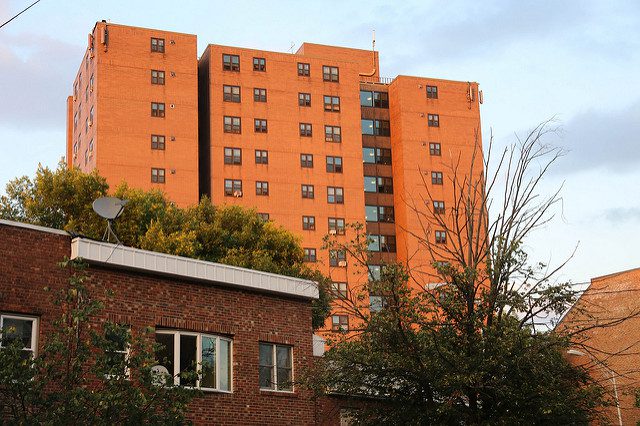

But public housing wasn’t always like this. John Atlas and Peter Dreier point out in “Public Housing: What Went Wrong?” that public housing was originally intended to help the working poor and young families starting out. It really was supposed to be a “hand up, not a handout.” But after World War II things changed. The home construction industry, fearing competition, began to sway policy to limit the scope of public housing, restrict its use and force it to take the form – concentrated, high-rise apartment buildings in marginalized areas of big cities – that we’re all familiar with today.

It’s these behemoths, like the State Street corridor in Chicago, a “community” of forty-eight high rises housing 25,000 people in four square miles, that are the legacy of powerful industries, corrupt and racist policies and far from benign neglect that Joseph Shuldiner must deal with; not to mention an army of local housing authority managers whose responsiveness to Washington is often tenuous at best; a budget that would have to increase many times over just to catch up to current needs; and a perception by society that public housing is beyond redemption and that the government is incompetent at solving these problems.

Partnerships Gained In Struggle

Shuldiner talks about hard issues he faces, in a Shelterforce interview. One issue is tenant organizing. Shuldiner accepts the need for tenant groups – involved citizens – to be empowered to run their own lives, effect change in their communities and lobby for change in the local and national arenas.

But his acceptance of tenant organizing has his limits; some groups are counterproductive, he feels, when they organize “against” the public housing authority. Madeline Talbott, the National Field Director for the ACORN Tenants Union disagrees. Too many local authorities have agendas that are not in the best interest of the tenants; too many pay no attention to tenants; and too many use tenant organizations to simply rubber stamp their plans. ACORN’s alternative calls for a partnership of equals gained in struggle.

Getting Past the Sadness

And struggle we do, some of us more than others. A few weeks ago we received a book of photographs taken by Helen Stummer over a period of thirteen years of a group of people in Newark, NJ’s Central Ward. Stummer’s photos are sad. They show us how hard life can be. But, beyond the sadness, there is a deep well of strength, resilience and hope. Stummer’s subjects – who quickly became her friends – are fighting for their lives. When they lose, her photos bring us close to the pain; when they win, we can share the joy.

It’s hard to describe the power of pictures without sinking into cliché, so, in lieu of a review, we present a brief portfolio of her images from No Easy Walk (available in print version only).

Tending the Garden State

Patrick Morrissy, Shelterforce Editor and Executive Director of Housing and Neighborhood Development Services, Inc. (H.A.N.D.S) of Orange, NJ was honored by the WorldWorks Foundation as the 1994 recipient of the Tending the Garden State Award. H.A.N.D.S received the award for “innovation in developing multi-dimensional approaches to permanently end hunger and homelessness in New Jersey.” Previous winners have included the New Communities Corporation, Isles Community Garden Program and the Mayor of Trenton.

Way to go, Pat.

Comments