Glossary

Total development cost, or TDC: The summed costs of financing housing: the cost of purchasing the land, hard costs (construction materials and labor), and soft costs (including design fees, legal fees, permitting fees, and developer fees).

Capital stack: The combination of multiple funding sources that developers assemble to cover the cost of a project.

Senior loan: The first mortgage on a development. The senior lender gets paid before any other debt-holders and before the owners of the property. They have the first legal claim to the asset if the borrower defaults on their debt. Because this investment carries the lowest risk, it tends to have the lowest interest rate.

Subordinate loan: A loan that takes a subordinate position to the senior loan. The subordinate lender gets paid after the senior lender, but before any owners of the property. Because this investment carries a moderate risk, it tends to have a moderate interest rate.

Equity: Cash generated by the sale of an ownership stake in the project to an investment partner (also known as the limited partner). Equity financing is repaid by a share of the remaining cash flow after the loan payments are made and by the proceeds when the building is sold. Because this investment carries the highest risk, it tends to have the highest rate of return.

Internal rate of return (IRR): A complicated investment metric that factors in not just how much an investor is paid but when they are paid.

Net operating income (NOI): The remaining income of a housing development (from rent and fees) after subtracting operating expenses (like property tax and maintenance) and capital expenses (money set aside for larger repairs, like a new roof).

Supply-side subsidies: Up-front, one-time investments that add cash into the capital stack that doesn’t have to be repaid (such as grants or tax credits).

Demand-side subsidies: Funds that supplement a project’s net operating income (like vouchers, which increase rental revenue, and property tax discounts, which decrease operating expenses).

While the need for more affordable housing is widely acknowledged, the financial intricacies involved in creating and sustaining such housing can be obscure. This explainer aims to demystify the foundational concepts of affordable housing finance, covering capital stacks, subsidy options, and the cost of capital. By understanding these components, stakeholders can better navigate challenges and effectively support affordable housing development.

Capital stacks

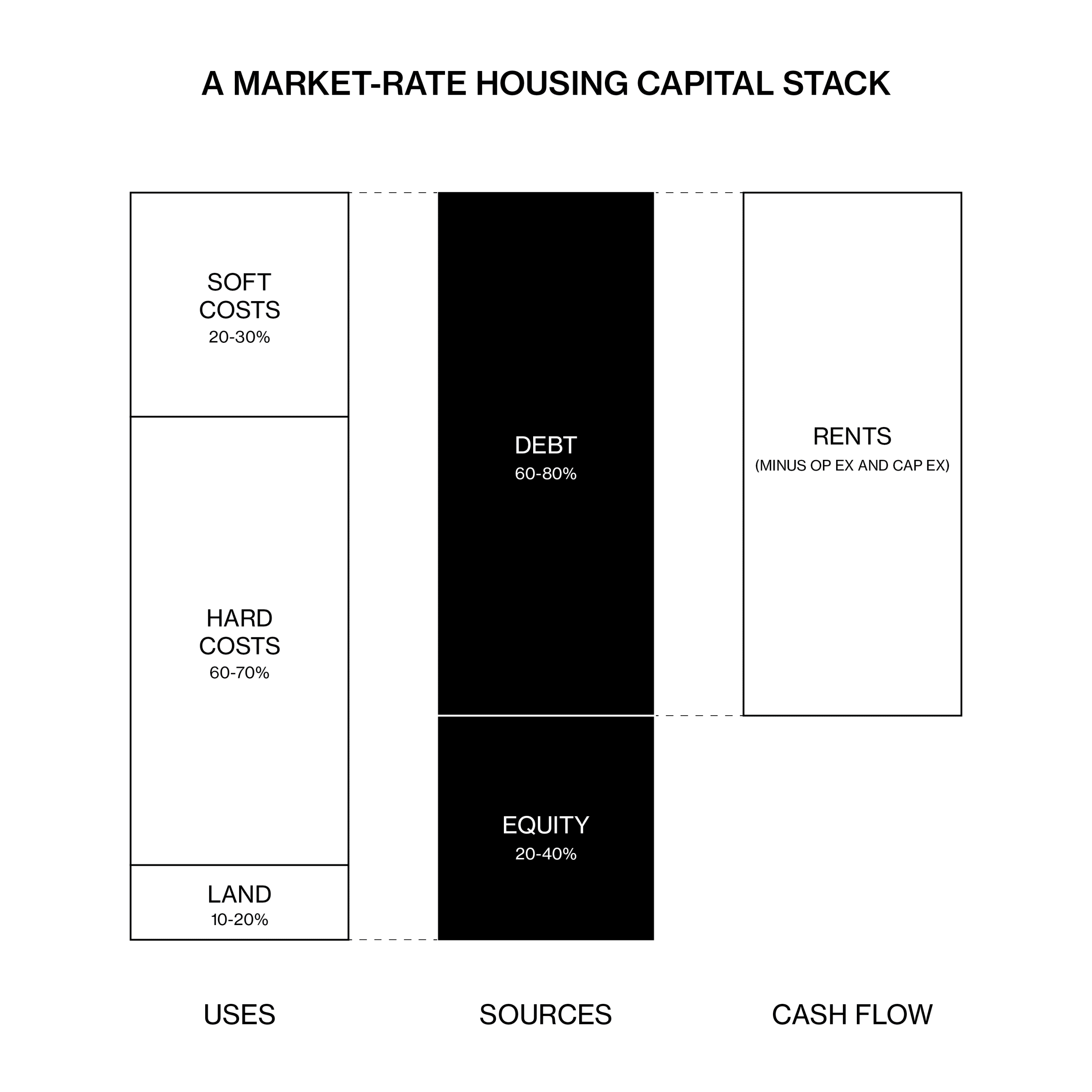

A natural first question is: What does it cost to provide affordable housing? To start, we need to understand both the costs of development and how those costs are financed. The total development cost consists of three components: land, hard costs, and soft costs. Land costs typically account for 10 to 20 percent of the total development cost. Hard construction costs—the cost of materials and labor—typically account for 60 to 70 percent of the total. Soft costs—like design, legal, permitting, and developer fees—typically account for 20 to 30 percent of the total cost.

Developers rarely have enough cash on hand to fund the entire development cost themselves. So they combine various sources of outside capital, which are repaid later through the project’s rent revenue and value as a real estate asset. This assemblage of funding sources is called the capital stack. To make a deal work, the sources of capital (money to pay for the project) must equal the uses of capital (total development cost).

The capital stack is built with debt and equity. Debt financing is typically structured as a loan: Money is borrowed and repaid over time with interest. The monthly payments are almost always fixed and if the borrower does not pay, the lender can foreclose on the housing development. The lender does not have any ownership of the property, and once the debt has been repaid, the relationship with the financier ends.

Equity financing is cash that comes from the sale of an ownership stake in the project to an investment partner (also known as the limited partner). Equity financing is not repaid in fixed payments. Instead, the investor owns a share of the project’s remaining cash flow after debt service, and a share of the proceeds when the building is sold.

In most capital stacks, the primary source of funding is a bank loan, referred to as a senior loan. Just as it does with a home mortgage, the bank sizes the loan based on the monthly income available to make payments. For a multifamily housing development, the net operating income (NOI) is the income from rent and fees minus both operating expenses (like property tax and maintenance) and capital expenses (money for larger repairs like a new roof). In a market rate deal, the senior loan typically covers 60 to 80 percent of the project’s financing, depending on the interest rate.

Whatever is not financed with debt is funded by selling equity. Equity investors take more risk than the bank (if things go wrong, the senior loan gets paid first), so they expect a higher rate of return. This makes equity the more expensive capital in the stack. The developer is often required to invest their own money too, ensuring they have a stake in the project. Once the project is complete and generating rent income, the bank loan is repaid in fixed installments, and the developer and equity investor split the remaining net operating income. The developer and investor also have ownership stakes in the building, so a large part of their total return comes from the eventual sale of the building.

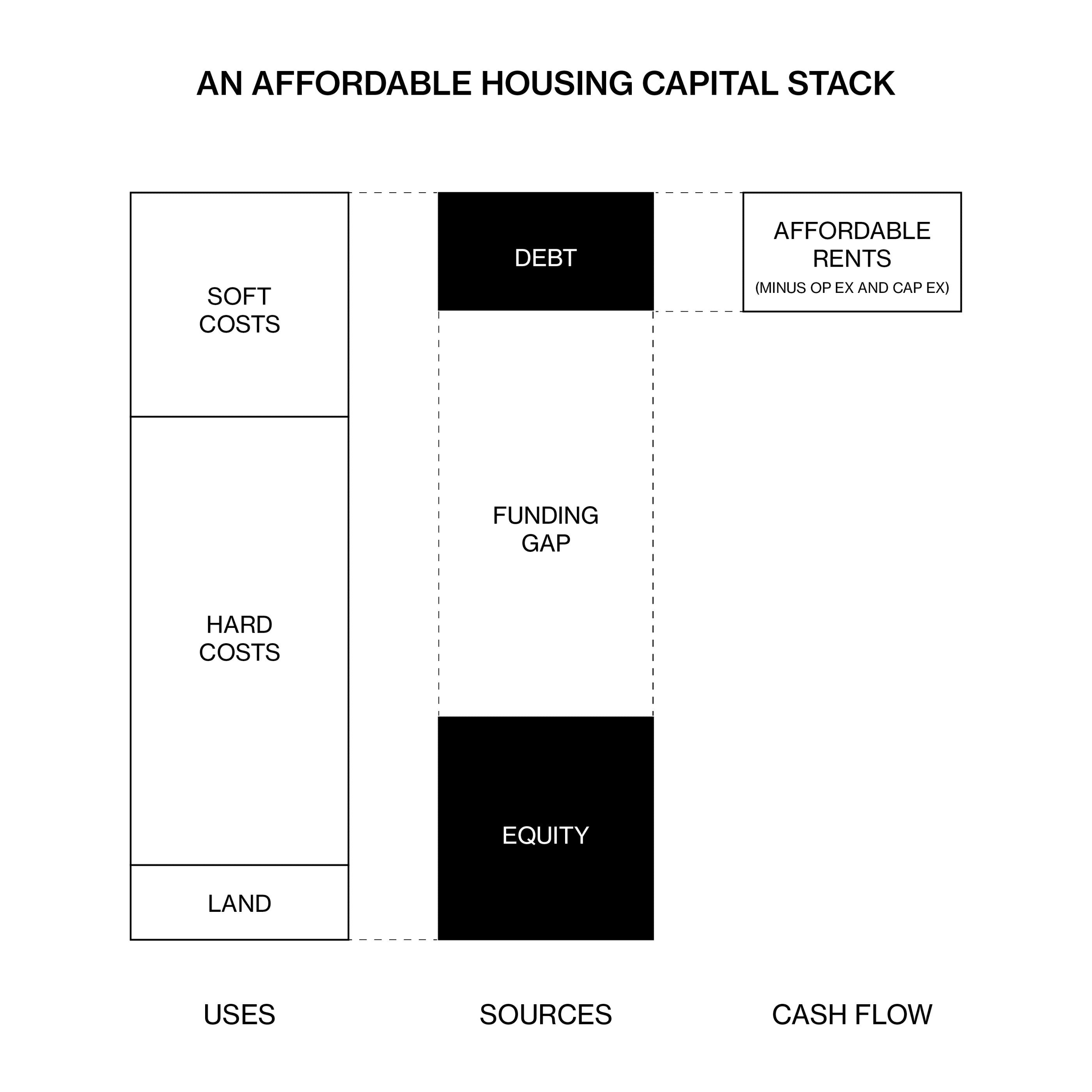

What makes affordable housing difficult to finance is that the senior loan is a significantly smaller portion of the capital stack. Affordable rents are lower, but operating expenses are largely the same, squeezing the net operating income.

With less money available to make mortgage payments, the project cannot support a large loan. This creates a funding gap. The challenge of affordable housing development is figuring out how to close this gap.

What Does It Look Like In Practice?

If we have 100 units in an apartment building that each rent for $1,500 per month, the NOI might be $1.26 million after expenses. If the units rent for $780 (affordable to a household making $15 per hour), the NOI would be $396,000. Cutting the rent in half decreases the NOI by nearly 70 percent.

Closing the Gap

There are three approaches to closing the funding gap.

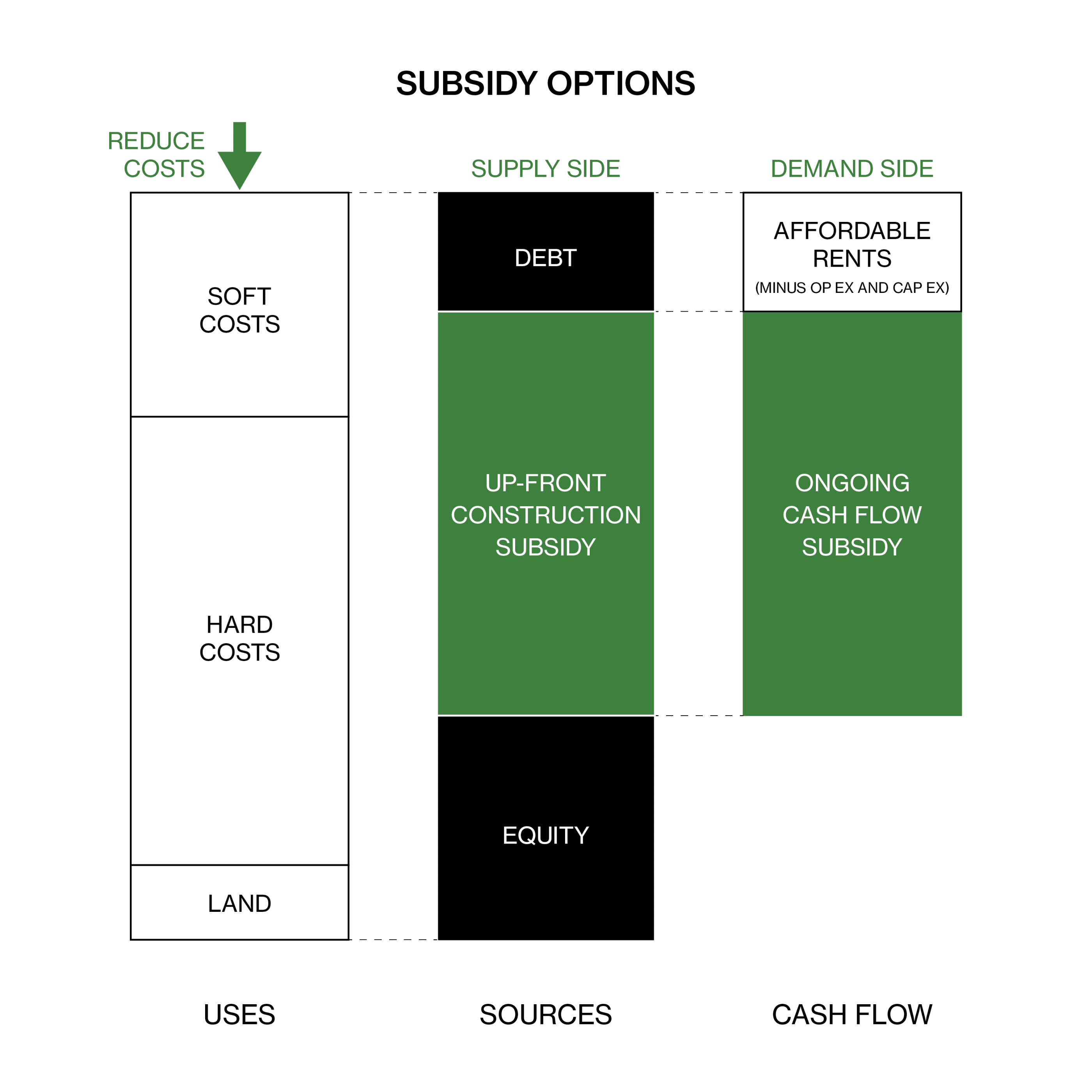

First, the overall project cost can be reduced. The project can use donated land to reduce land costs, get permit fees waived to reduce soft costs, or value engineer the design to reduce hard costs (in other words, change the building design and finishes to reduce the cost of construction.)

However, this can only go so far—at a certain point, cheap construction will cost more down the road. Beyond what can be achieved by cost reduction, most projects need subsidies to close the gap. Subsidies for affordable housing fall into two categories: supply-side and demand-side. Supply-side subsidies, like grants and tax credits, add cash into the capital stack that does not need to be repaid. These subsidies directly fill the funding gap with up-front, one-time investments that do not make demands on the building’s future cash flow. Demand-side subsidies, like vouchers and property tax discounts, supplement the project’s income so it can support a larger senior loan.

Vouchers increase rental revenue, and property tax discounts reduce operating expenses, both of which increase the project’s net operating income. These continuous operating subsidies allow the project to take on a bigger loan up front, helping to close the funding gap. In practice, affordable housing developers in the U.S. need a mix of everything to make the numbers work.

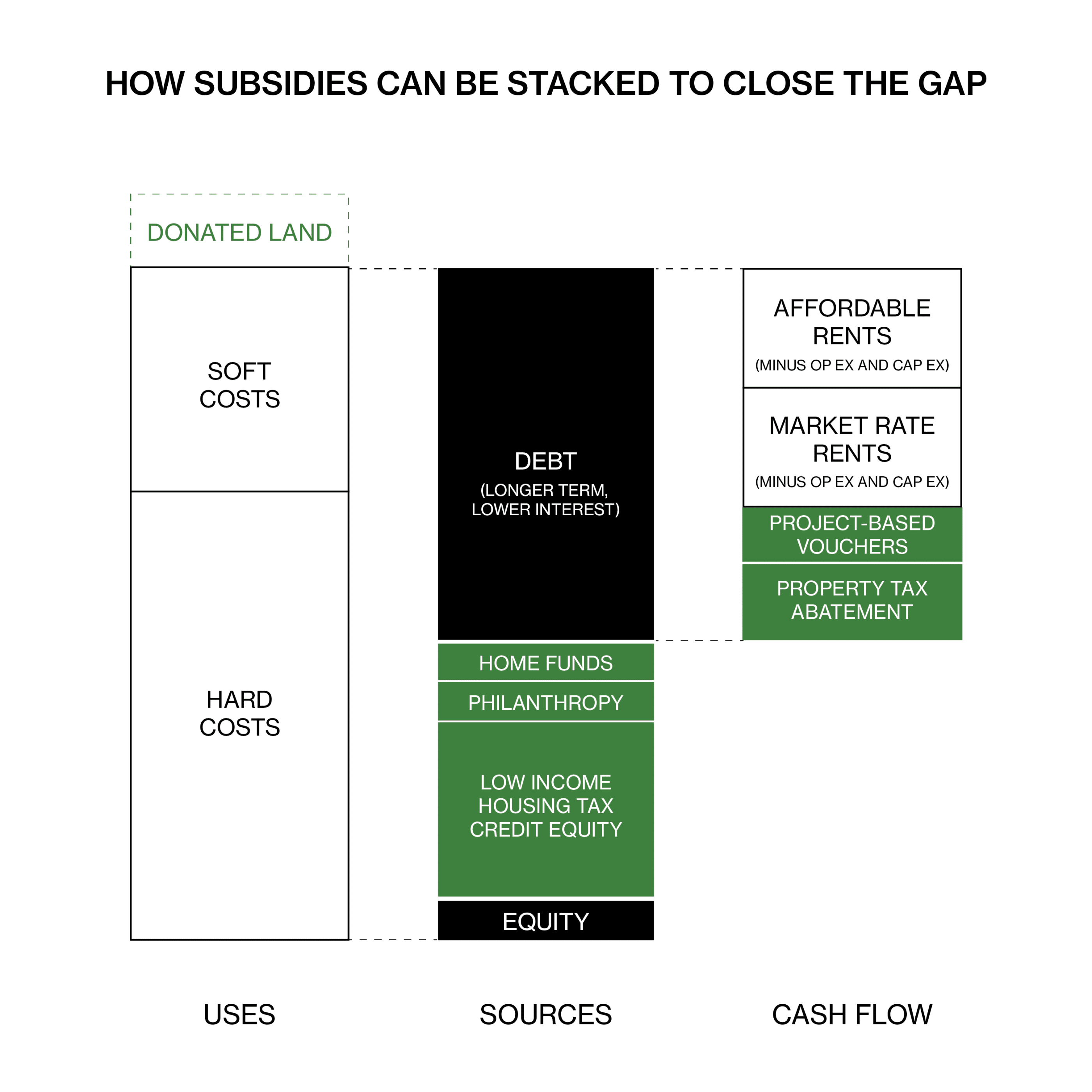

Take the example below. Costs are reduced with donated land. Supply-side subsidies include a grant from the federal HOME program, investor equity from the federal 4 percent low-income housing tax credit (LIHTC) program, and a philanthropic grant. Demand-side subsidies include some market-rate units and project-based vouchers to boost rental revenue, along with a property tax abatement to reduce expenses. Each funding source has its own application, requirements, timeline, and availability. Getting one of these deals to work can take years, and it is far more difficult to pull together than a regular market rate real estate development.

The Cost of Capital

Besides direct subsidies, the funding gap can also be closed by reducing the cost of capital. Almost all projects are funded with a combination of debt and equity, and both must be repaid with interest or returns. The interest rate and return expectations change with the economy, and this can dramatically change the cost of using that capital.

With a senior loan, the maximum loan amount is based on the monthly revenue available to pay it back. When interest rates go up, a larger share of the payment goes to interest, so the same monthly payment cannot support as big a loan. For example, if a 100-unit apartment building rents all its apartments for $1,500, its net operating income might be $105,000 per month after expenses. At a 4 percent interest rate, the building could afford a $22 million loan, but at an 8 percent interest rate, it could only support a $14 million loan. The higher interest rate creates an $8 million gap in the capital stack. Conversely, providing a loan with a reduced interest rate or extended term can close the funding gap without requiring direct subsidy dollars. This is an indirect approach to subsidizing affordable housing: offering capital at a below-market interest rate.

Subordinate Loans and Equity

Subordinate loans are another tool for closing the funding gap. These are smaller, infill loans that are made after the senior loan. They sit in between senior debt and equity: the senior loan is paid first, then the subordinate loan, then equity.

Commensurate with their mid-level risk, subordinate loans from the private sector have higher interest rates than senior loans but lower return expectations than equity. Public and impact investment funds can offer subordinate loans at a below-market rate with more favorable terms, helping to close the gap while still earning some return on their investment. For public and impact investors, the advantage of this type of subsidy is that it’s evergreen: the funding will be repaid with interest, so it can be recycled into new projects.

Below-market equity can also reduce a project’s cost of capital. Equity is the riskiest type of investment in a real estate deal, so equity investors typically expect high returns—often in the range of 15 to 20 percent. These returns are measured using the Internal Rate of Return (IRR), a metric that considers not just how much an investor earns, but also when they earn it.

Because IRR accounts for the time value of money, it often requires far more cash than a loan to meet expectations. For example, a 10-year, $10 million loan with fixed payments at a 7 percent interest rate would cost $3.9 million in total interest. But—taking the most extreme scenario where the investor isn’t repaid at all until year 10—a $10 million equity investment with a 7 percent IRR would require a return of $9.7 million. If that same investment targets a 20 percent IRR, the return would be $52 million.

These high return expectations put pressure on project rents and sale prices, but without an equity investor, most real estate deals simply don’t happen. Equity is essential, but it’s also the most expensive capital in the stack. When public or impact investors are willing to invest equity at below-market returns, they can act as catalytic, last-mile capital to close the funding gap and make the deal happen.

Taking a market-rate multifamily deal and simply lowering the rents leaves us with a massive funding gap. Filling the gap requires us to both find direct subsidies and shrink the size of the gap we begin with. Our limited and valuable direct subsidy dollars go further when they are layered with indirect subsidies, like lowered land costs, guaranteed loans with lower interest rates, below-market investment capital, or property tax reductions. The levers need to be coordinated on a deal-by-deal basis. But by understanding how those levers are connected, policymakers and investors can find creative solutions to effectively close funding gaps and make affordable housing projects achievable.

Comments