Top Takeaways

- The Supreme Court is considering a request from landlords that could declare COVID-19 eviction moratoriums unconstitutional, potentially opening the door to challenges against other tenant protections.

- The current legal challenge is an expansion on a recent Supreme Court decision overturning California’s union-organizing protections for farmworkers.

- If the Supreme Court takes the case and rules in favor of the landlords, it could redefine property rights under the Constitution and have significant negative implications for tenant rights beyond eviction moratoriums.

The Supreme Court is considering a request from California landlords to hear a case that could declare the expired COVID-19 eviction moratoriums unconstitutional under the Fifth Amendment. If the landlords win, it could open the door for them to challenge other tenant protections. For most of the United States’s history, the Supreme Court has left landlord-tenant relations up to state and local governments. The Constitution has nothing to say about rent and little to say about eviction. And yet, there is now a real chance that tenant protections across the nation will be at risk. After the Supreme Court shifted to a 6–3 conservative majority, a long-running property rights movement has gained a foothold in its campaign to turn the Fifth Amendment into a tool for championing property rights over all other rights.

The Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution gives us the “right to remain silent” when arrested and the right to “plead the Fifth” when interrogated. In the shadow of these rights, well known from TV crime dramas, there is the “takings clause.” That clause says that if the government takes your private property, it must pay you for it. When the government wants to build a highway through your backyard, the Fifth Amendment requires the government to pay for the land it uses. But what it means for the government to “take” property includes more than physically seizing land. It also means affecting your use of it. The Supreme Court has said that the government takes property when it flies military planes low over farmland, “grazing the treetops and terrorizing the poultry.” It takes property when it requires a building owner to let cable companies install a television cable and other equipment not much larger than a shoebox on an apartment’s rooftop. And it takes property when it requires owners of beachfront real estate to allow the public to walk across their land to access the sand and waves. The Fifth Amendment also doesn’t apply only to land or buildings. The government also takes property when, for example, the Raisin Administrative Committee—a New Deal-era committee in Fresno—keeps part of a farmer’s crop off the market to boost the price of raisins.

Throughout the 20th century, the Supreme Court decided in a number of cases that there are two basic types of “takings.” The military planes, television cables, beachgoers, and lost raisins were all “physical” takings. Those types of cases are clear cut and can be easy for the property owner to win. The second type is a “regulatory” taking. This kind happens when the government’s regulation “goes too far” in restricting the use of property. Regulatory takings cases are vague, complicated, and hard to win. The seminal case that established the law for a regulatory taking involved a railroad company’s proposal in the late 1960s to build a skyscraper on the roof of Manhattan’s ornate Grand Central Station. (New York City said no; the railroad company sued and lost.)

The line between a “physical taking” and “regulatory taking” can be blurry. Only lawyers can divine why putting a television cable on an apartment roof is a physical taking but stopping a skyscraper from being built on a train terminal’s roof is a regulatory one. Naturally, property owners that sue would prefer that their case be treated like the easier-to-prove “physical” taking. This has led to a legal campaign by various libertarian and conservative groups to get more government regulations declared “physical” takings rather than “regulatory” ones. A recent target of this campaign was labor organizing protections in California.

The National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) is the nationwide law that protects employees’ right to unionize at work. That is, unless you’re a domestic worker or farmworker. Those workers have been excluded from the NLRA’s protection from the beginning. In 1975, California passed a state law—the Agricultural Labor Relations Act (ALRA)—supported by César Chávez and Dolores Huerta of the United Farm Workers. The ALRA partly closed the gap in the NLRA and brought the right to unionize to California’s agriculture industry. Shortly after it was enacted, a regulation was passed that gave union organizers the right to meet with workers on the farms, fields, ranches, and packing plants where they work. Organizers could enter the property for up to three hours a day—one hour before work, one hour during lunch, and one hour after work—to talk about unionizing.

Cedar Point Nursery is a large strawberry farm in the rural northern California town of Dorris. The town’s population is not much bigger than the nursery’s seasonal and full-time workforce of 500. It was home to “the USA’s 2nd Tallest Flagpole” at 200 feet (“garners immense interest from travelers and residents alike” according to one online reviewer) until it was bumped to apparent third place by a Missouri flagpole last year. In 2015, toward the end of the strawberry harvesting season, organizers from the United Farm Workers came onto Cedar Point’s property early in the morning with bullhorns. Cedar Point viewed these organizers as trespassers invading their private property. A few months later, Cedar Point teamed up with a much bigger fruit company, the Fowler Packing Company, to sue in federal court. They wanted the court to declare the organizer-access regulation unconstitutional. The fruit companies’ lawyers were from the Pacific Legal Foundation, a conservative libertarian legal group that “defends Americans’ liberties when threatened by government overreach and abuse.”

The Cedar Point v. Hassid case made its way to the Supreme Court in 2020. The fruit companies’ argument was simple: The California regulation gives union organizers the right to walk onto their private property to speak with farmworkers and that’s tantamount to the government “taking” their property without paying for it. In June 2021, the Supreme Court agreed with the fruit companies. The six-member majority of Republican-appointed justices emphasized that the “right to exclude” others from your property is “one of the most treasured rights of property ownership.” Because the California regulation took that right away by stopping the fruit companies from kicking union organizers off their land, the regulation was an unconstitutional “taking” under the Fifth Amendment. It didn’t help that the regulation said that union organizers can “take access” to the property, a point that Chief Justice John Roberts repeated seven times.

With the Supreme Court’s Cedar Point decision in hand, the Pacific Legal Foundation and other property rights advocates turned to another group of owners seeking to bolster their treasured “right to exclude”—landlords. But there is one case that stands in their way: a 1992 Supreme Court decision written by Sandra Day O’Connor called Yee v. Escondido.

Thirty miles north of San Diego is the avocado town of Escondido. In 1988, its citizens passed Proposition K which brought rent control to Escondido’s 30 mobile home parks. Within a year, over a dozen lawsuits were filed by park owners challenging Proposition K. One of those lawsuits was brought by John and Irene Yee, owners of two mobile home parks. They argued that the rent control ordinance combined with a California state law that limits the reasons a park owner can end or not renew a mobile home lease (what modern-day tenant advocates would call “just cause” or “good-cause” eviction protections) resulted in a physical “taking” under the Fifth Amendment. The Yees, joined by other landlords, said that the government had taken “the right to occupy the land indefinitely at a submarket rent” and given that right to mobile home park tenants. In other words, Escondido and California had put unconstitutional limits on the Yees’ right to evict.

The Supreme Court unanimously ruled against the Yees. The Court said that “a physical taking” of property is when the government “requires the landowner to submit to the physical occupation of his land,” but “no such thing” had happened to the Yees. Instead, the park owners had “voluntarily rented their land” and the “tenants were invited . . . not forced upon them by the government.” Because the state and local laws only regulated this landlord-tenant relationship, there was no physical taking of property by the government.

In the three decades since Yee was decided, the ruling has been used to reject claims by landlords that pro-tenant regulations are unconstitutional physical takings, forcing landlords to argue the much tougher “regulatory” taking claim, which they then typically abandon or simply lose in court.

Almost immediately after Cedar Point was handed down in 2021, landlords found new hope. They started bombarding courts with arguments that said Cedar Point had implicitly narrowed the impact of Yee. Under Cedar Point all kinds of tenant protections were now unconstitutional physical takings under the Fifth Amendment. Landlords have used Cedar Point to attack New York City’s rent control and good-cause eviction protections. They’ve gone after Minneapolis’s tenant-friendly rental application screening rules and its ban on public assistance discrimination. They also targeted Oakland’s tenant relocation assistance ordinance and Seattle’s restriction on winter evictions. All of these attacks have been repelled largely because of Yee. That is, until the pandemic-era eviction moratoriums were challenged.

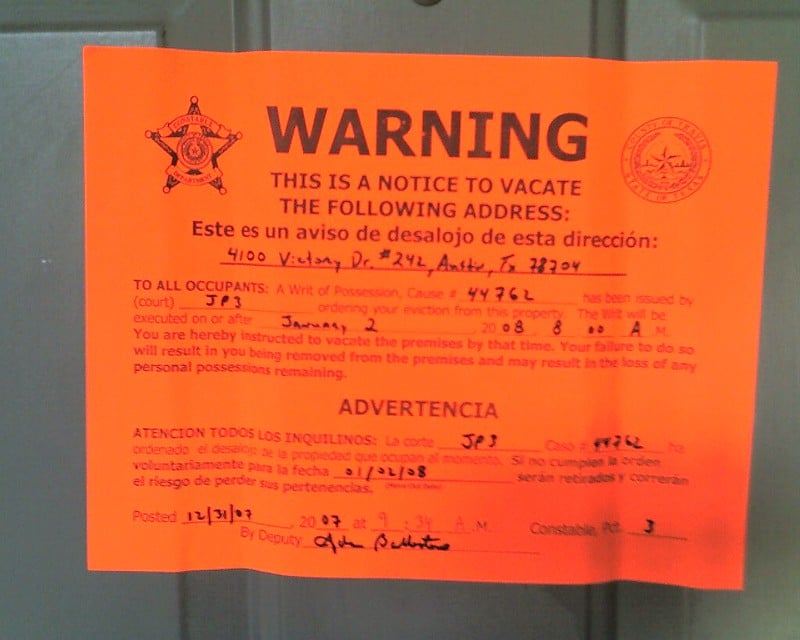

During the early years of the COVID-19 pandemic, at least 43 states passed emergency laws restricting evictions. Dozens of cities and counties passed local moratoriums on eviction as well. Los Angeles was one of them. Two months after the Cedar Point decision was announced, GHP Management Corporation—a California landlord of “luxury apartment communities” renting to “predominantly high-income tenants”—filed a lawsuit challenging L.A.’s eviction moratorium in federal court. They were not the first to do so. The Pacific Legal Foundation, representing two Washington state landlords, had already sued in federal court challenging Washington’s statewide and Seattle’s local moratoriums. Landlords in Minnesota sued Gov. Tim Walz over his executive orders restricting evictions. Even more landlords sued the federal government for the CDC’s nationwide eviction moratorium. The landlords in all of these cases claimed that the eviction moratoriums had “taken” their property under the Fifth Amendment and were unconstitutional without payment from the various local, state, and federal governments. Each relied heavily on Cedar Point to make their arguments before the trial court or on appeal. Like the fruit companies losing their “right to exclude” the union organizers, these landlords insisted they had similarly lost their right to evict tenants.

By the fall of 2023, the West Coast landlords had lost in court and GHP Management had appealed. The Minnesota landlords, on the other hand, had won. The Eighth Circuit, which decides appeals from Arkansas to North Dakota, ruled in favor of the landlords.

In May 2024, the Ninth Circuit (which hears appeals from western states), disagreed, and ruled against GHP Management.

Later that summer, the Federal Circuit in Washington, D.C., sided with the landlords and the Eighth Circuit, finding that the CDC’s moratorium could have been a physical taking. Using Cedar Point, the landlords had convinced these two federal appellate courts that Yee is on shaky ground.

This kind of disagreement among appellate courts easily catches the Supreme Court’s attention. It sees its role partly as resolving these divisions between different circuits. With that in mind, GHP Management headed to the Supreme Court to ask it to overturn the Ninth Circuit’s ruling and declare that the pandemic-era eviction moratoriums were unconstitutional “takings” that entitled landlords to millions in taxpayer-funded payouts.

In GHP Management’s petition to the Supreme Court, it devoted nearly all of its limited space to attacking Yee. If the Supreme Court accepts the case, the question in the conservative justices’ minds will likely be this: does Cedar Point and its “treasured rights of property ownership” outweigh tenant protections, or does Yee—a decades old case from southern California about mobile homes—survive?

The Supreme Court has already foreshadowed what its answer is likely to be if it takes GHP Management’s appeal. After the CDC extended its eviction moratorium for a fifth time in the summer of 2021, the Supreme Court took up an emergency request to pause the CDC’s order while the case challenging the CDC’s authority to issue the moratorium was appealed. The six conservative justices agreed to pause the CDC’s order during the appeal, in part because “it is difficult to imagine [the landlords] losing” the case. But perhaps more importantly, according to the justices, the CDC moratorium was harming landlords: “preventing them from evicting tenants who breach their leases intrudes on one of the most fundamental elements of property ownership—the right to exclude.”

If Yee’s holding is narrowed or overturned, much more than eviction moratoriums may be at risk. Since Cedar Point, failed legal challenges to New York City’s rent control and good-cause tenant protections have been brought to the Supreme Court. Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch have expressed interest in hearing those cases, but they have not yet gotten the necessary four votes for the Supreme Court to hear the case. If Yee falls, there will be little standing in the way of landlords getting the votes they need to roll back tenant protections. GHP Management’s lawsuit against Los Angeles may be the case that opens the door to a future with far fewer rights for tenants. Rent control, good-cause eviction, screening rules, anti-discrimination ordinances, and other tenant protections would no longer have Yee to stand behind.

Three California organizations have intervened in the GHP Management case to represent the interests of tenants—Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment (ACCE) Action, Strategic Actions for a Just Economy, and the Coalition for Economic Survival—and they will likely be looking for nationwide support if the Supreme Court takes the case.

The Court will decide whether to grant GHP Management’s petition in the coming weeks.

Comments