The Housing Choice Voucher program, better known as Section 8, helps low-income renters afford private-market housing by restricting their portion of the monthly rent to 30 percent of their income. The federal government pays the remainder. The program is run by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), which transfers its portion of the rent to local public housing authorities (PHAs) each month. The PHAs then pay landlords directly. But Section 8 is facing increased fiscal and administrative uncertainty under the current executive leadership. In late January, for example, Section 8 recipients nationwide wondered if February’s rent would get paid when the White House called for a freeze on all federal funding.

So, what happens when a Section 8 tenant pays their portion of the rent, but the government fails to pay its share? According to statute, the tenant cannot be held responsible for the unpaid amount. (HUD in an email declined to provide specific information, instead referring Shelterforce to the Housing Assistance Payments contract. The applicable information can be found on page 9, subsection 5d, which states that “PHA failure to pay the housing assistance payment to the owner is not a violation of the lease. The owner may not terminate the tenancy for nonpayment of the PHA housing assistance payment.”) HUD rules also prohibit landlords from demanding tenants cover the housing authority’s portion and may not evict tenants solely due to delayed or missing subsidy payments.

But that doesn’t mean tenants aren’t at risk. Here is more information on what protections HUD provides, how tenants should protect themselves, and what risks they still face.

How Tenants Are Protected

- Eviction restrictions: The HUD Occupancy Handbook (4350.3 REV-1) outlines procedures and grounds for terminating tenancy in HUD-assisted housing. It specifies that owners must follow due process and may not terminate tenancy without proper cause. Nonpayment of the tenant’s portion of rent can be grounds for eviction, but the handbook does not list nonpayment by the housing authority as a valid reason for eviction.

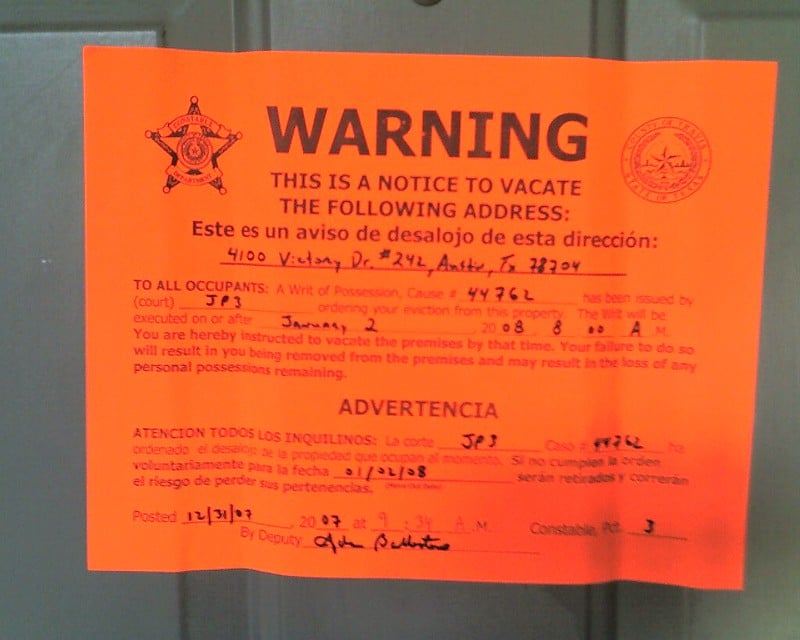

- Legal procedures: Landlords must follow specific legal procedures when attempting to evict a Section 8 tenant—this includes providing tenants with proper legal notice.

- Notification: Landlords must also notify the housing authority of any issues related to rent payments or lease violations. They cannot unilaterally decide to evict a tenant without involving the housing authority.

How Tenants Can Act

- Communication: If tenants are facing eviction due to the housing authority’s nonpayment, they should communicate with both the landlord and the housing authority to clarify the situation. They should keep any records, including proof they paid their portion of the rent and any emails or hard copies of written communications. If the exchange is verbal, they should write down what was said as soon as possible following the interaction.

- Legal assistance: Tenants may seek legal assistance and/or contact tenant advocacy groups—such as the National Alliance of HUD Tenants—to protect their rights and ensure proper procedures are followed. (Shelterforce compiled an informational page for tenants facing eviction, which can be found here.)

Although the Section 8 program is designed to incentivize landlords to participate by promising (and providing) reliable, government-backed rent payments, that guarantee can break down if a housing authority delays or fails to pay its portion. In such cases, landlords—who are still prohibited from collecting the missed subsidy directly from tenants—may face financial strain, particularly if they rely on timely payments to cover mortgages or maintenance costs. This could discourage landlords from accepting Section 8 vouchers in the first place, or prompt those already in the program to opt out once their contracts expire, further limiting the pool of affordable housing options for voucher holders.

Once landlords exit the program, voucher-holding tenants remain covered by local eviction protections. A handful of states have good cause eviction protections, meaning a landlord can’t refuse to renew a lease unless the tenant has violated the terms of the lease. However, most renters still won’t be able to afford market-rate rent in the unit they previously used a voucher to help pay for. (Landlords in places with source of income protections can’t officially opt out of accepting vouchers, but without good cause protections in place, they may still decline to renew a lease on unspecified grounds.)

Comments