This article is part of the Under the Lens series

Banana Kelly Place, at 830 Fox St. in the Bronx, has had fewer violations than its market-rate neighbors due in part to its funding model. Photo by Gregory Jost, Banana Kelly

New York City’s housing market is a multibillion-dollar industry, and one that has expanded rapidly over the past three decades. By one estimate, the values of multifamily properties increased between 400 percent and 600 percent between 2000 and 2018 in every borough except Staten Island. This climate has fed a boom of real estate speculation across the city, driving up rents, pushing out longtime residents, and creating “super-gentrified” islands of wealth in neighborhoods where lower-income New Yorkers had lived until the recent past.

|

|

“Speculation” in a housing context is a slippery term to define, but some of its harbingers are well known: Anonymous LLCs scooping up homes in lower-income neighborhoods, then reselling them quickly at wildly inflated prices; property owners “warehousing” vacant apartments in the midst of a housing shortage, betting on a turn in the market or a spike in land values to create more profit than a rental income stream could.

But the way multifamily buildings are financed is also a strong signal of speculative action, and one that can tell us not only how likely a building’s tenants are to be displaced, but how likely they are to be living in poor housing conditions, according to “Gambling with Homes, or Investing in Communities,” a report from the Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC) and the University Neighborhood Housing Program (UNHP).

The report found that tenants in buildings that had recorded “speculative events”—like a steep increase in prices between sales, or a large amount of debt borrowed against the building—had significantly worse outcomes than tenants in buildings without these markers of speculation. Landlords who bought properties at higher values, or who took on more debt against their buildings, were 1.5 times more likely to execute an eviction warrant against their tenants than owners of comparable buildings in similar neighborhoods.

Speculative financing was also associated with buildings being in a poorer state of repair. Buildings with higher debt loads and buildings purchased at higher sales prices had 2.7 times the number of housing code violations from the city Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD).

According to Julia Duranti-Martínez, program manager at LISC and one of the report’s co-authors, “This really undercuts the claim that landlords are generally reinvesting in their properties, and reinforces what tenant leaders and organizers have been saying for quite some time, which is that this is primarily a strategy for extracting profits from buildings, not for investing in their upkeep.”

The report homes in on two forms of speculation, both of which rely on the rising value of the building as an asset, rather than its income from rent payments, for profit. The first occurs when a landlord purchases a multifamily building with the intent to resell it at a higher price, a strategy that works particularly well in neighborhoods undergoing gentrification, or where public sector decisions, like zoning changes or infrastructure investments, are likely to lead to higher property values in the near future.

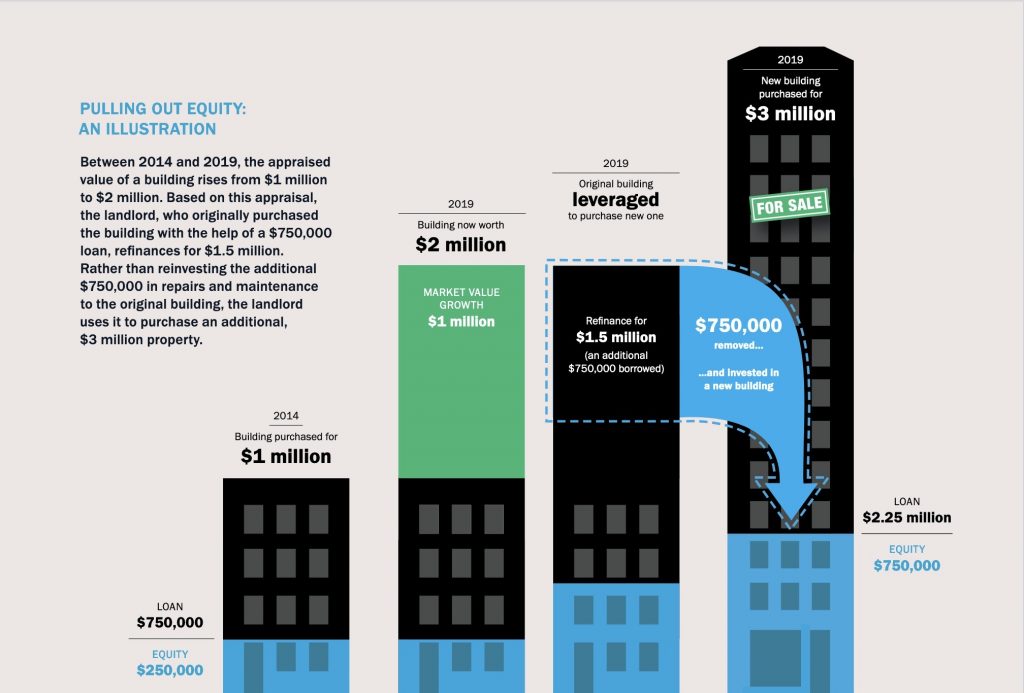

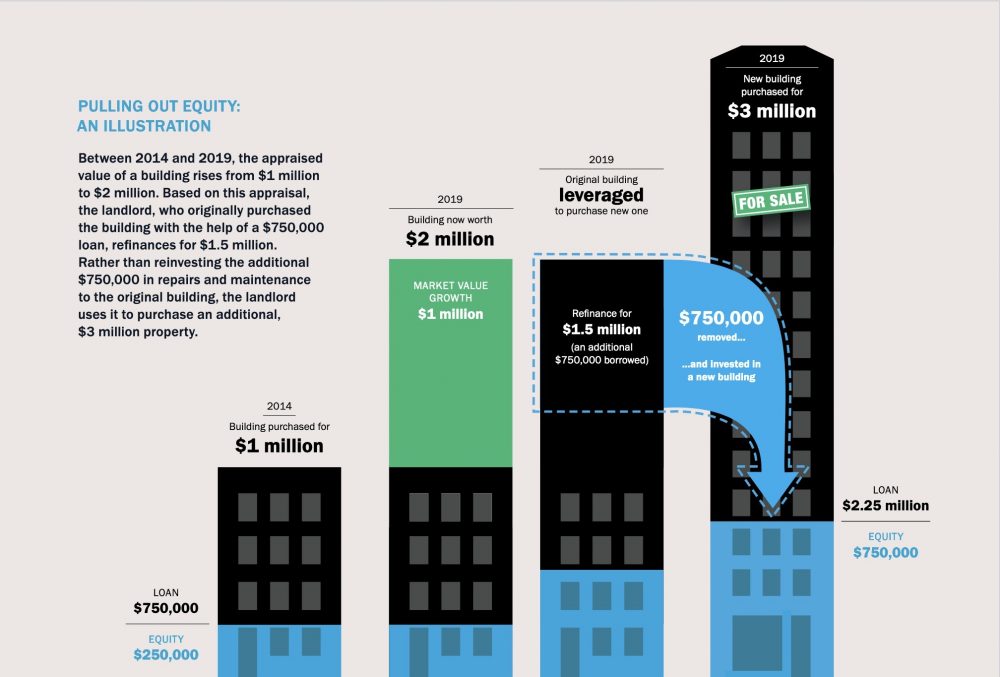

The second speculative strategy is a little more complex, and possibly more insidious: using the building as leverage to access relatively cheap capital in the form of a refinanced mortgage loan, which can then be diverted to other investments. For example, if a building’s assessed value rises significantly over five years, the owner can refinance the building and use the larger loan amount to purchase a second property, and then a third, and so on.

An illustration from “Gambling with Homes, or Investing in Communities,” a report from the Local Initiatives Support Coalition and the University Neighborhood Housing Program.

In the meantime, tenants in the original property are more likely to be dealing with low-quality repairs, deferred maintenance, and a higher number of HPD violations than tenants in buildings that aren’t as loaded with debt. Rather than investing in upkeep, the report suggests, owners who take on higher debt levels are more likely to use the building’s rental income to service their repayments, while letting maintenance issues slide.

Since this entire strategy hinges on the rising value of the building, letting it deteriorate may seem a little counterintuitive. But not when you understand that “the value of multifamily apartment buildings, for the most part, has very little to do with the actual, physical conditions of the building, and a lot more to do with the market conditions of the neighborhood,” Duranti-Martínez says.

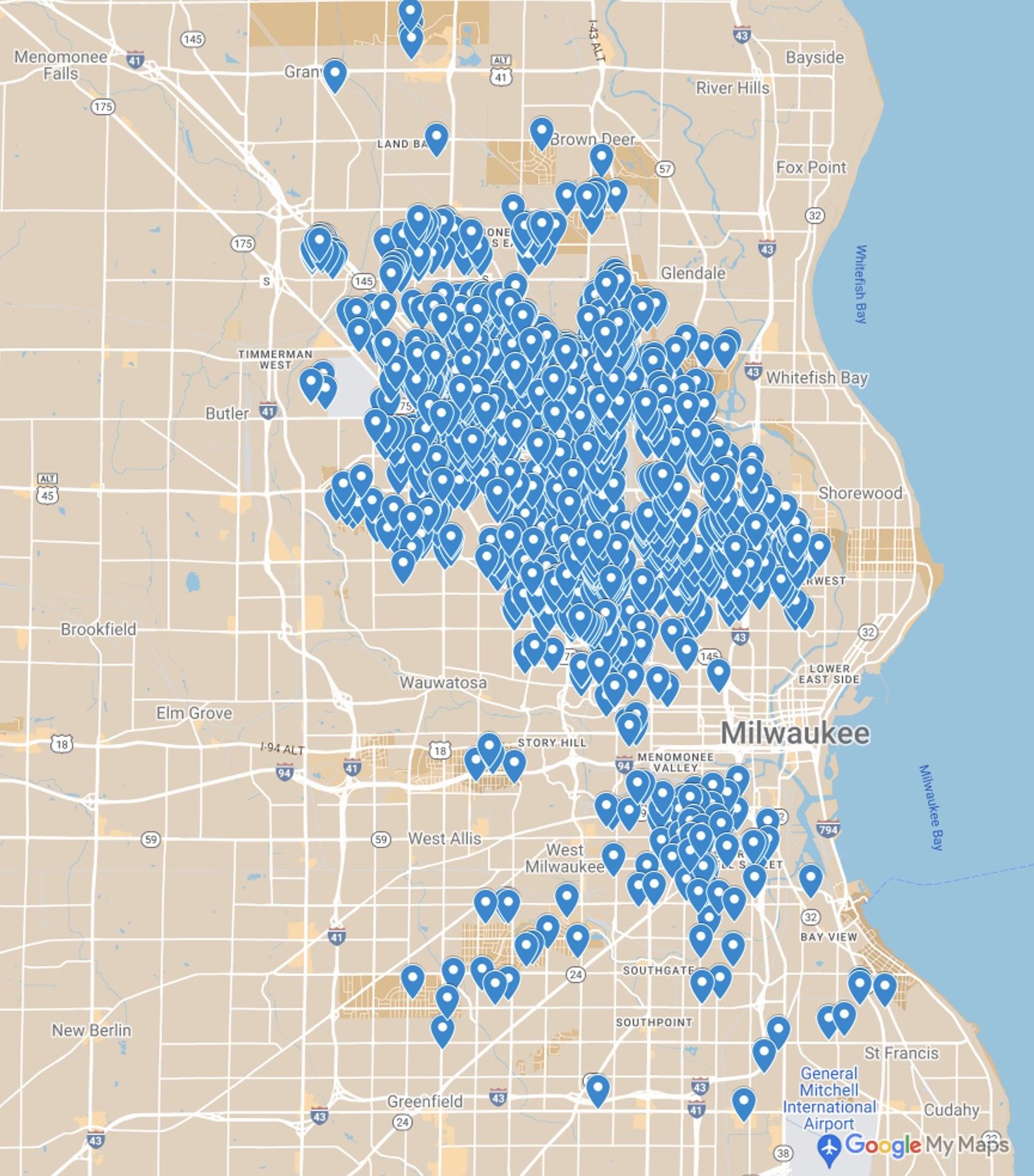

And what kind of neighborhood conditions tend to draw this type of speculation? In New York City, Black and Latinx communities showing signs of gentrification—specifically population increases and increases in residents with college degrees—but that also still have very high poverty rates experience speculation the most. Census tracts with 30 percent poverty had a 14 percent higher rate of landlords taking out the maximum amount of additional debt against their buildings as compared with those with 20 percent poverty. Upper Manhattan, the Bronx, and central and eastern Brooklyn saw both forms of speculation the most, and the highest number of eviction filings.

“It isn’t actually the wealthy white neighborhoods in Manhattan that are leading to these really speculative profits. It’s Black and brown communities with a history of policies like redlining and urban renewal that led to a lot of abandonment, disinvestment, and decreased property values. And in the absence of bold policy interventions, that creates the conditions for this flood of really speculative capital and predatory investment,” says Duranti-Martínez.

Breaking the Cycle of Speculation, Disinvestment, and Displacement

There are a number of policy maneuvers, like good cause eviction, right to counsel, or a Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act, that could help chip away at the speculative business model in New York City and other hot housing markets across the country, while creating greater housing stability and healthier living conditions for renters.

Passing good cause eviction protections could make buildings less appealing to speculators whose intention is to refuse the occupants a new lease so the units can be re-rented at a higher rate. A good cause eviction bill, which provides tenants with certain protections against eviction, is in committee at the state legislature, but it failed to pass this session. Right to counsel laws (which are in place in New York City and are also under consideration at the state level, but failed to pass this session) and harassment protections could help even out the power imbalance between tenants and speculative owners who want them out. A Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act or Community Opportunity to Purchase Act could transfer buildings from speculative owners to tenants or mission-driven community groups.

But one of the strongest protective factors against speculation is affordable housing investment. The report analyzed affordable housing data from NYU’s Furman Center, focused on community, nonprofit, and tenant ownership models. The researchers then compared this data with data from the Building Indicator Project, and compared these buildings with those that did not receive affordable housing subsidies.

Buildings with these ownership models saw about one-half to two-thirds fewer maintenance violations than unsubsidized apartments, including luxury buildings and new construction. In the Bronx, those buildings have one-third to one-fifth the number of violations per unit compared to unsubsidized buildings.

What explains this significant difference in upkeep? And why wouldn’t the trend break in the other direction, with the buildings intentionally serving lower-income renters showing poorer maintenance quality?

Duranti-Martínez attributes the difference to tighter requirements surrounding most affordable housing subsidies compared with capital accessed through mortgage refinancing. The requirements prevent those affordable housing investments from being funneled elsewhere. “That financing is part of a mission to steward affordable housing. It’s not a profit-generating strategy,” she says. The fact that affordable housing assets don’t tend to be resold at such dramatic price increases, because there’s a cap on what can be charged for rent, is also a protective factor.

In the Bronx and Upper Manhattan, the Banana Kelly Community Improvement Association helps shelter over 1,400 affordable apartments from the speculative cycle. The group provides affordable housing development, preservation, community organizing, case management, and supportive housing rental assistance, and has supported innovative community ownership initiatives throughout the city. Many of the properties Banana Kelly rehabilitates have had owners who pulled out high levels of debt against them, without reinvesting in maintenance or improvements. These buildings are usually run-down, and require a substantial investment to rehabilitate.

941 Intervale Ave. is being renovated by Banana Kelly, after it was rescued from the cycle of speculation and the cluster site program. Photo by Gregory Jost, Banana Kelly

“We tend to get buildings that have gone through the speculative cycle, and have been through the wringer in terms of violations,” says Gregory Jost, director of organizing at Banana Kelly and co-creator of the Building Indicator Project that supplied much of the report’s data. He sees the current speculative climate as a continuation of a long history of wealth extraction in the Bronx, where large numbers of property owners torched their buildings to collect fire insurance during the downturn of the 1970s. Just as taxpayers footed the bill for the fire resources and the state insurance pool then, taxpayers pay the price for the cycle of speculation and disinvestment that exists today, Jost says. “When you strip equity out of the buildings, extract resources, and let them deteriorate, and then you want to bring them back into a decent condition, it costs the city and state a lot of money.”

One of Banana Kelly’s properties, 830 Fox St. in the Bronx, was singled out in the report as a case study for having significantly fewer violations than its market-rate neighbors. Since the property was transferred from the city to Banana Kelly in 1995, it has received a mix of Low-Income Housing Tax Credits, city tax exemptions, New York City Housing Development Corporation funds, and HUD HOME program financing to maintain its affordability. The building had just 2.7 average violations per year during the study period, compared to 16.8 for similar buildings. Part of this is because it’s a newer building, Jost says, but part of it is due to its funding model. “The affordable housing subsidies, and mission-driven ownership, tenant ownership, it takes the speculative piece out,” he says.

Jost adds that improved code enforcement at the city level could curtail the speculative business model of pulling equity out of buildings without funding their upkeep. But much of it comes down to more-responsible lending through the government-sponsored enterprises like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac that often fund the cycle, he says. “You would think that when a landlord takes out more equity against a building, they would be required to make repairs. But instead, they’re using that money to increase their portfolios.”

Currently, banks that lend to property owners who harass tenants or neglect maintenance can get credit under the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) as long as the loans are for projects in low-income census tracts. Jost suggested that loans to predatory landlords—which could be flagged by examining open housing code violations, or records of harassment—should not be eligible for CRA credit. The three federal agencies that enforce the CRA are currently revising its regulations.

The true solution to disinvestment and displacement may be entirely reimagining how we think about housing. “There’s a competing interest between housing as a social good for people, and housing as an investment tool to make profit,” Jost says. “And what we’re trying to do is skew that competition toward the social good.”

[Correction: The original version of this article was unclear about what factors the LISC report considered to constitute signs of gentrification.]

|

|

The article writes:

“And what kind of neighborhood conditions tend to draw this type of speculation? In New York City, lower-income, Black, and Latinx communities showing signs of gentrification experience it the most. According to the report, an increase in a census tract’s poverty rate from 20 percent to 30 percent was associated with a 14 percent increase in landlords taking out the maximum amount of additional debt against their buildings.”

If areas “showing signs of gentrification” experience speculation, and “an increase in a census tract’s poverty rate from 20 percent to 30 percent” correlates with speculation, does this mean that increased poverty is a sign of gentrification?

This seems like a proofreading error that needs to be corrected. Or am I missing something?

Hi Michael — I see your point! I’ve checked with the original report, and I believe the intended point is not to say that moving from 20 to 30 percent indicates gentrification, but that those with 30 percent poverty are more ripe for gentrification (along with other measures), and they saw more speculation. I think the wording does need some clarification though. I’m going to check with the report authors to be sure and then issue a clarification. Thanks for pointing that out!

Michael, here is the corrected paragraph: “In New York City, Black and Latinx communities showing signs of gentrification—specifically population increases and increases in residents with college degrees—but that also still have very high poverty rates experience speculation the most. Census tracts with 30 percent poverty had a 14 percent higher rate of landlords taking out the maximum amount of additional debt against their buildings as compared with those with 20 percent poverty. Upper Manhattan, the Bronx, and central and eastern Brooklyn saw both forms of speculation the most, and the highest number of eviction filings.” Thanks again for bringing it to our attention!