The Chicago River. Photo by Fred Faulkner, via Flickr, CC BY 2.0

I remember taking a Chicago River boat tour and marveling at the glass skyscrapers and their proud entrances and mirrored reflections in the rippling water—with the exception of the 1929 Civic Opera Building. The docent pointed out that a century ago, the river was so polluted that the building was constructed to turn its back on it.

This is what came to my mind in 2016 when a group of Northbrook homeowners tried in vain to dissuade its elected officials from approving a massive “campus of exclusivity,” as one naysaying plan commissioner described it. The project was designed to turn its back on residents and front the interstate highway. Today this mixed-use development includes an athletic “resort” and luxury housing, which indeed advertises itself as a “straight shot north from Chicago via the Eden [sic] Expressway,” offering “close proximity worlds away.”

“Will this development contribute to fostering community or an appreciation of nature?” is less important to power brokers than, “Is this marketable to people who want to zip in and out conveniently?” This kind of thinking encourages vertical gated communities with privatized amenities, which limit contact between residents who live within and outside of their developments. This lowers the quality of life for all.

The Northbrook project shows how a progressive concept—in this case, “transit-oriented development”—can be co-opted for a decidedly self-serving end. Environmental and affordable housing advocates have used the term “TOD” to promote walkable and diverse communities by income, age, and race—myself included when I helped to write a handbook on this very topic for suburban planners in 2015, Quality of Life, (e)Quality of Place.

Unfortunately, “transit-oriented development” has become a politically correct term for business as usual: serving people as consumers rather than as social and emotional beings. One would think that government would take its charge as the “public sector” to heart and serve as a caretaker of the commons. Instead, our municipalities wield their zoning power quite thoughtlessly, in the belief that the “highest and best” use of land should necessarily yield the highest and best dollar.

In my own town of Skokie, I could hardly believe that the village would decide to sell taxpayer-owned land for high-end housing—but that’s exactly what happened with a new high-rise downtown development, now called Highpoint, whose first tenants moved in last month.

At a Village of Skokie board meeting Dec. 18, 2017, following public pleas for mixed-income housing at the site, Mayor George Van Dusen responded that the village would not require developers to include any low-cost apartments, adding, “A little over a year ago, the Village undertook a marketing study before we put out our Request for Proposal. The marketing study told us the one area of housing that we do not have is luxury rental . . . that’s the one thing that was missing. And as a consequence, we put out a Request for Proposal. And sure enough, the marketplace told us that was indeed what we were missing.”

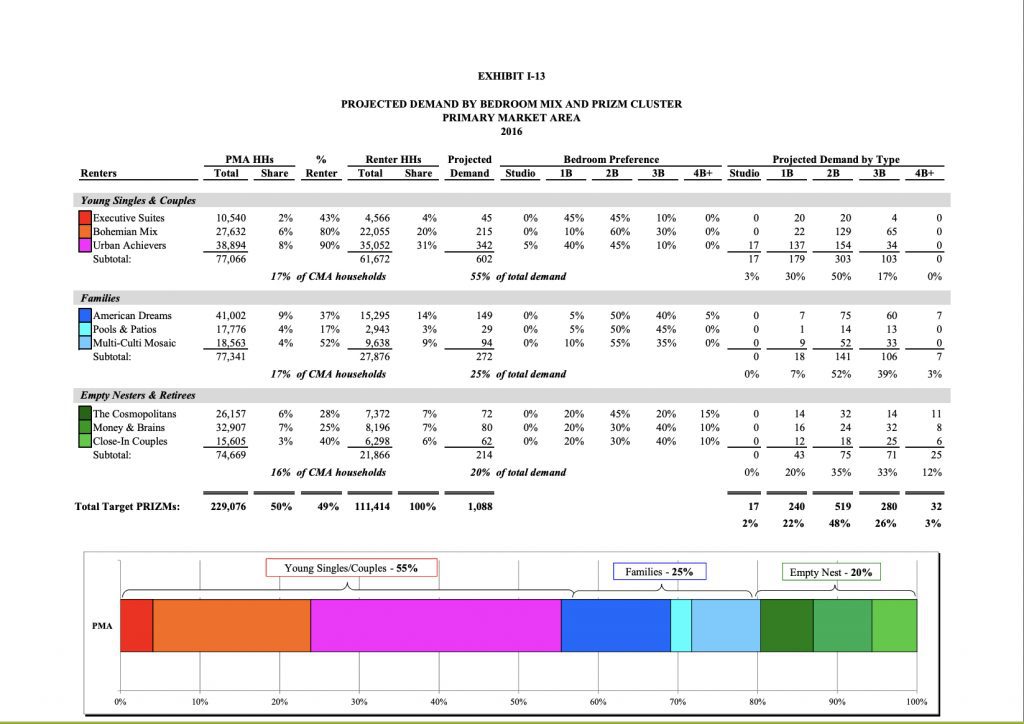

As a result of my Freedom of Information Act request to the Village of Skokie, I obtained that marketing study, which was conducted by The Concord Group (Strategic Marketing Opportunity Analysis and Product Program Recommendation for a Planned Apartment Site in Skokie, Illinois). It’s composed of maps charting employment, commuting patterns, and new housing by price, life expectancies, and households, which are divided into consumption-based subcategories like “Bohemian Mix” and “Money & Brains.”

This is what our community looks like when it is treated as a “competitive market area,” with living people reduced to abstract brands:

This is the real “housing plan” that dictates development in our region. According to the study, the ultimate goal for this frontage on Oakton Street, located in the heart of town, is to attract people earning over $100,000 a year who fall into the categories of “young singles & couples” who are “leaving the Loop”—or leaving the main section of Downtown Chicago—with “-2 to 2 year old children” (yes, children who won’t be born for two years) and “long-term Skokie residents looking for homeownership movedown” (if that is even a word).

Five “comparables” are mentioned in the Concord study, all luxury residences. One of those buildings, Evanston’s E2, unambiguously zeroes in on students and young professionals, imagining they would find it attractive to live where you can “grab your laptop and get comfortable at coffee shops like Starbucks, BrewBike, or Colectivo Coffee.”

[RELATED ARTICLE: What Does ‘Gentrification’ Really Mean?]

The “community amenities” listed on the website for Highpoint make no reference to schools, parks, the library, or Skokie neighbors themselves in all their diversity. Instead, we have things like a roofdeck park with stunning views, designer lounges, and even a dog run and pet wash.

Highpoint seems to define “community” as the common area of a restricted and secured building or complex. Even Fido doesn’t have to mingle with the riffraff. It is a definition that would appeal only to those wishing to live gated lives.

This Skokie scenario is not unique. It is illustrative of how, since the 2008 mortgage meltdown, suburbs that seemingly did all they could for decades to prevent high-density housing are choosing to embrace what the Concord study terms “apartment products.” Of course, the catch is that these “products” still cater almost entirely to the well-off.

This upmarket strategy underscores the reality of rampant inequality in America, with fewer people holding a greater proportion of wealth than we have seen in over a century. It also reinforces racial segregation. The sobering fact is that despite 50 years of fair housing laws, more than 80 percent of major metropolitan areas were more segregated in 2019 than in 1990, according to a study released in June 2021 from the University of California at Berkeley.

Just how real is this claimed need for “luxury rental”? Skokie’s Consolidated Plan to HUD shows a very different profile of demand than the Concord study. We learn in the “Con Plan” that more than 40 percent of Skokie households are paying more than 30 percent of their incomes for housing (the “start of housing instability”), with 4,309 renters handing over more than half their incomes to landlords.

The Highpoint project will propagate not diversity and neighborliness, but rather separation and isolation in Skokie. As Jane Jacobs asserts in her classic text, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, “It is wrong to set one part of the population, segregated by income, apart in its own neighborhoods with its own different scheme of community.”

It is time for us to reclaim the word “community” as a network of integrated relationships in an open neighborhood.

Inclusive community is better for our health, both as a society and as individuals. Our need for one another has been made poignantly clear during the pandemic as loneliness engendered by enforced physical separation now affects more than one-third of Americans. In her recent New York Times article, “Does Co-Housing Provide a Path to Happiness for Modern Parents?,” Judith Shulevitz points out that “co-housing,” in which families live in communities that share common amenities like a kitchen and child care, are more salutary for us than the “detached single-family house—the lonesome cowboy model of domestic architecture.” The luxury vertical gated community with its isolated apartments is just another manifestation of this.

Real alternatives exist to this “lonesome cowboy” living situation. I direct a Chicago nonprofit organization called Housing Opportunities and Maintenance for the Elderly (H.O.M.E.), which owns and operates two intergenerational shared housing residences. Although they can close the door and spend private, quiet time as they choose, the residents, mostly older people, dine and socialize together. And they thrive in this intentionally communal environment. H.O.M.E. encourages a sociable lifestyle through the design of its buildings, which feature common areas, sunlight, gardens, staff in residence, and varied programming.

Hope Meadows, a community of 80 homes on a former Air Force base in central Illinois, is another variation on co-housing. Whereas H.O.M.E. focuses on seniors living with young adults as resident assistants and families with children, Hope Meadows is a mutual support system for children adopted through the foster care system. In this case, the role of seniors is to assist the families.

But over time, “intentional neighboring” blurs the distinction between the helper and the helped in daily acts of “social caring,” as Brenda Krause Eheart, co-founder of Hope Meadows, reflects in her new book Neighbors: The Power of the People Next Door. Eheart, a retired sociology professor from the University of Illinois, finds that when people live in places designed to encourage mutual support, their lives become more purposeful, which has a positive effect on mood and health. Seniors in particular become more oriented toward the future, “looking forward to seeing Johnny graduate.”

From this perspective, the proliferation of gated and locked housing “units,” the sanctioning of a transit-oriented, fast-lane culture in which real life is “over there,” has a kind of sadism to it. Engaging in relationships with others, as Eheart quotes psychologist Marvin Seligman, is “a rock-bottom fundamental to well-being.”

Intentional neighboring, finds Eheart, is “a response to all kinds of human problems as they emerge across the landscape of our culture, especially those problems that marginalize and isolate whole groups of people for their various differences. … In truth, intentional neighboring can exist in any setting that includes homes and willing neighbors.”

Eheart would agree with Shulevitz that we have the power to effect change through local government:

“A wholesale revision of zoning codes could lead to a new built environment, one that would nudge us toward a new mind-set … [encouraging] solidarity and fellow feeling rather than aloofness: Co-housing communities are centered on their greenswards; we need more parks. Co-housing puts people before cars; towns and cities should do the same. Co-housers live together, meaning they are around in case of need; the least inspiration we can take from that is to make our housing stock more varied, less focused on the nuclear family, so that members of extended families and groups of friends can be there for one another, too.”

The Northbrook, Skokie, and Evanston developments enable a bubble lifestyle, encouraging residents to minimize contact with society outside their buildings. By pigeonholing people, these buildings maximize loneliness and exclusion. They are antithetical to democracy and civic participation, as residents have no direct stake in the welfare of their neighbors, the environment, or the town itself beyond a scenic view (of the next town). We need to start afresh, promoting housing that embraces genuine community and creates opportunity for connection and conviviality. We turn our backs on one another at our own risk and to our own detriment.

Editor’s Note: This piece first appeared on Patch.com.

Thank you for this article. As someone with close to fifty years in the affordable housing field, mostly in New York City, your concerns are very much appreciated. I’ve always though a mandatory 80-20 program makes most sense, even if it is more incremental. But communities should be respected… plus, some communities can benefit from the economic boost provided by wealthier residents. Jane Jacobs brought to fore some great ideas, however, affordability wasn’t one of them. Anyone familiar with the West Village knows that there are few low income households living there.

While I don’t discount the ability of high-rise development to become “vertical sprawl,” I find this issue quite low on the priority list of things to spend time rallying against. Energy spent decrying a luxury tower next to a freeway is energy not spent combating the real sprawl that continues to decimate our climate and offers no solution to the second affordability crisis that our low-income households now face (which is, the forcing of automobile ownership on vulnerable households just to participate in society). Calling luxury housing in TOD the “status quo” is just NIMBYism in another form.

Chris, we are actually saying the same thing but from a different lens. You are absolutely right that we prioritize accommodating the car and all the pollution and sprawl that go with it. James Kunstler in “The Geography of Nowhere” is especially eloquent about this. What I’m saying is that developers and towns are stretching and abusing the term “TOD” to include proximity to highways, rather than evaluating walkability and public transit. Moreover, they are allowing and even encouraging luxury lifestyles that actually depend on isolation from the masses. The second half of my article suggests a set of specific solutions, all of which address affordability and the climate crisis. My perspective is using community as a tool in itself.

You really do hit a nerve with this story. The three quarter century long fetish for single family home zoning exclusivity is now rearing its ugly head big time. Yet you will hear this issue talk about despite the all too obvious telltale signs, most notably escalating homelessness. The unsung heroes might be the paycheck to paycheck crowd who are on the verge of bankruptcy if a major unexpected expense comes along. They are financially stuck in place with little hope for escape save for an extreme stroke of luck such as a lottery win. Many had to take work for much less than a former job may have paid. Thus they were referred to as Generation Limbo. I replied to article with LIMBO in all caps because I was able to come up with the perfect acronym: Lower Income Mostly Beyond Overhaul.