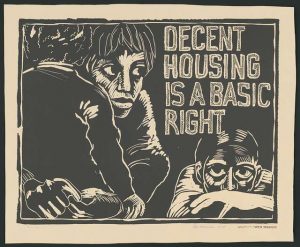

Poster by Rachael Romero, via Library of Congress

It’s hard to overstate the transformation in the politics of public safety over the course of 2020. After the murder of George Floyd and corresponding uprising in Minneapolis, a nationwide movement of unprecedented scale arose to grieve and to resist anti-Black racism. The Overton window on policing shifted rapidly: community-based accountability and notions of #CareNotCops entered the mainstream as credible alternatives to incarceration, and centrist leaders once content with criminal justice reform began to speak of defunding and even abolishing the police. The groundswell in the streets turned the tide in halls of power. Long-standing demands to identify and uproot the carceral state’s connections to chattel slavery are finally being heard and heeded.

This kind of sea change is overdue in housing policy, where incremental, rather than transformative, approaches have traditionally been the norm despite visionary contributions from housing activists. The exigencies of 2020 require a bold, new course. Both the severity of pandemic-spurred rental arrears and the might and potential of the Movement for Black Lives urge a different way forward. As we argue in a new paper, the movements for prison and police abolition offer vital lessons for housing justice.

Defining Abolition

Despite its increased salience in contemporary racial justice platforms, abolition—as a mode of mobilization and social change directed at the criminal legal system and elsewhere—remains widely oversimplified and misunderstood. Abolitionist movements find their origin in W.E.B. Du Bois’s notion of “abolition democracy.” Du Bois posited that the relics of slavery persisted after Emancipation because white lawmakers and vigilantes thwarted newly freed Black citizens’ efforts to build democratic institutions that would allow them full participation in America’s social and economic life. Contemporary abolitionists thus organize to “fully abolish the oppressive conditions produced by slavery.” In the criminal legal contexts, abolitionists have powerfully articulated how phenomena from mass incarceration to police violence both originate from and perpetuate the subjugation and brutality of chattel slavery. Abolitionists thus seek both to abolish prisons and policing as relics of slavery, and to build up new institutions that will both make these criminal legal systems unnecessary and replace them with alternatives that facilitate human flourishing.

Housing policy is as implicated as criminal law in the American schema of racialized social control, and is as apt a target for abolitionism. The racism that pervades racial terror and the Great Migration, exclusionary zoning and redlining, New Deal exclusion, and predatory inclusion is as apparent as the racism that pervades the Black Codes, convict leasing, Jim Crow, and mass incarceration. Concomitantly, housing justice is central to the community care that abolitionists envision.

Taking an abolitionist lens to housing policy would require a commitment to identifying and dismantling the relics of slavery that persist at the levels of cities, neighborhoods, and buildings. Many of these relics can be seen in how the criminal legal system affects both access to housing (through background checks and exclusionary legal mechanisms, such as “crime-free ordinances”) and the lived experience of residents affected by discriminatory or excessive policing and surveillance. But the vestiges of slavery pervade housing even more broadly and deeply. As Du Bois observed, after the formal abolition of slavery, most freed men and women were denied access both to land ownership and to equal employment opportunities. In both Southern and Northern cities in the decades following Reconstruction, white residents defended their hoarded opportunity with mob violence. Both during and beyond Jim Crow, white supremacy—through government and private enterprise—constrained the social and financial mobility of Black Americans. Scholars such as Richard Rothstein and Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor have documented how federal housing agencies first excluded Black households from homeownership opportunities, then shifted course to facilitate their exploitation through predatory lending mechanisms. The result has been pernicious and persistent racial disparities in wealth, homeownership, and access to opportunity in all its forms.

[Related: The Not-So Hidden Truths About the Segregation of America’s Housing]

Yet the housing field has yet to fully reckon with the anti-Black racism that pervades our work, too often accepting the boundaries white supremacy has drawn around what is possible. We may think of racism in housing through a historical lens—as if it were solely the preserve of Robert Moses and other long-deceased and widely denounced figures—or with unease, as if acknowledging and addressing racism would threaten the objectivity we are trained to strive for, or any benefits of the work we do. This must change.

Linking Abolition and Housing Justice

Engaging with abolitionism would first entail envisioning what housing justice would look like in abolition democracy. The voices of residents and of grassroots movements should be central to this vision, but we might imagine that housing justice encompasses, at minimum, ample safe and affordable housing; abundant wealth-building opportunities for Black households and communities; and a severing of the link between geography and opportunity. Abolition then asks what foundational conditions are necessary to make such a world possible and suggests that we should direct resources toward those ends. Research documenting the conditions of “high-opportunity” neighborhoods—today inhabited primarily by affluent white households—is instructive here. Access to food, jobs, and health care; well-resourced schools and libraries; and parks and green spaces can be foundational conditions for housing justice. Going deeper, we might imagine that such a world also requires investment in services that would address the root causes of or otherwise provide meaningful treatment for substance abuse, domestic violence, and mental health concerns.

Abolition is, in the words of scholar and activist Angela Davis, “not only, or not even primarily . . . a negative process of tearing down.” Nevertheless, abolition also compels us to imagine the obsolescence of institutions that fail to serve their designated purpose, prove resistant to reform, and perpetuate oppression. Just as prison and police abolitionists operate in pursuit of a world in which prisons and police are not only nonexistent but obsolete, we might ask: What would it take to make eviction, emergency shelter, or similar institutions unnecessary?

Consider, for example, housing court through an abolitionist lens. In theory a forum in which landlords and tenants can each vindicate their rights, housing courts instead operate in many cases as debt-collection mills against low-income tenants of color. Contemporary policy approaches have tended to focus on fortifying housing courts through additional resources: more lawyers, say, or more interpreters. Some of these reforms might indeed make conditions materially better for the tenants who pass through housing court. But abolitionism requires, at a minimum, that we not stop there, and instead also consider the foundational conditions necessary for a world without housing courts. Since a world without housing courts would necessarily be a world without housing instability, funding a diversity of housing types and guaranteeing everyone a home might be part of fulfilling an abolitionist vision. So might stronger tenant protection laws, more equitable community development approaches that discourage speculation and displacement, and expanded employment opportunities and higher wages for low-income workers.

Abolition also offers lessons for affordable housing development. Greater access to quality, affordable housing is undoubtedly part of a more just future. However, affordable housing developers have often been too ready to quietly accept the significant faults in the systems they work within. Since the 1970s, the federal government has been “getting out of the housing business,” transitioning from publicly constructed and managed housing to a more market-oriented, public-private model. The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) epitomizes this transition. In subsidizing development, it creates new affordable units and attracts private capital to disinvested areas. Yet the credit does not fully bridge the housing affordability gap. Qualifying properties may serve households at 50 to 80 percent of area median income, despite the dearth of affordable housing for extremely low-income renters and the preponderance of BIPOC within the population of extremely low-income renters. The credit’s affordability restrictions are set at 15 years, threatening families with housing instability and their communities with neighborhood change should owners decide to raise rents after the restrictions expire. Bringing an abolitionist lens to bear on the tax credit, and on affordable housing development more broadly, entails recognizing that units subsidized by the credit are often confined to economically and racially segregated areas, as well as exploring the ways in which both proponents of the tax credit and its critics have equated safety and opportunity with proximity to whiteness. If abolition counsels in favor of building new systems that truly uproot institutional racism, the credit seems insufficient—yet the housing field has spilled much more ink over how to tinker with LIHTC than on social housing models that center racial equity and dedicate public dollars to serving highest-needs households in perpetuity.

Finally, because abolitionists seek to be led by and materially support those most affected by the relics of slavery, an abolitionist approach would also compel our field to rethink its relationships with social movements. Our efforts are often guided by data-driven pragmatism that gets in the way of visionary approaches. As a result, we conceive incremental strategies for even the most egregious disparities. We offer term-limited assistance to households whose rent and wages will not reach parity within a year’s time; provide “light touch,” service-free housing to households burdened by intergenerational trauma; and construct “workforce housing” despite the dearth of affordable units for households at the bottom of the market. When movements call us to pivot from these transactional efforts to more transformational ones, articulating clear policy prescriptions, we dismiss them as naive and unrefined. How might we relinquish the paternalism and credentialism in our field? What would it mean to turn to encampment protesters, public housing organizers, and rent strikers for expertise? Abolition is a framework through which we may discern the false distinctions we make between impacted populations and activists, whom we keep at a distance, and business leaders and industry stakeholders, whom we draw in for consultation and public-private task forces.

As our examples suggest, shifting to an abolitionist approach will not be easy. Unpacking the racism within housing and community development while undoing the opportunity hoarding and milquetoast solutions our work has wrought is not a small feat. At a minimum, abolition requires us to redirect scarce resources. At its most complex, abolition raises difficult questions. For example, there is the tension between housing as an asset class and housing as families’ secure base; the tension between investing in the public provision of housing and investing in reparative wealth-building opportunities; and the tension between interventions that meet present needs and interventions that are “nonreformist,” i.e., working toward the equitable future that abolitionists favor.

Despite its complexities, abolition holds tremendous promise for the housing field. Technocratic solutions are an inadequate fix for housing policy’s bitter history of racism and expropriation. Such solutions also obscure visionary, bottom-up approaches to housing justice. Following abolitionists’ lead, we can think critically about the racism in our work, set ambitious end goals, build genuine relationships with frontline communities, and foster conditions and institutions to make those visions a reality. This trailblazing moment should not pass us by.

Thank you so much for forwarding this idea of abolition within the housing field. I fully agree. As you continue to explore, I would ask to also look at the issue from Native American and African American Indigenous culture/identity linkages to land ownership. I feel it is so important to acknowledge property ownership, not just increased in rental affordable housing, in all pathways towards racial reconciliation, equity, and beloved community. Thank you!

Loved this article! One note is that there is a 30-year required affordability period for all LIHTC projects. This has been in place since 1990 and many state tax credit allocating agencies require even longer affordability periods, such as California which requires 55 years. There is a short 15 year compliance period during which the tax credits can be recaptured but the legally enforceable affordability covenant extends for the full 30 years.

Please continue to publish pieces on this topic! I wonder if there are communities working on the entirety of a platform like this, grounded in abolition principles? And if you have recommended further reading?