Grenfell Tower after the tragic fire. Photo by flickr user PaulSHird, CC BY-SA 2.0

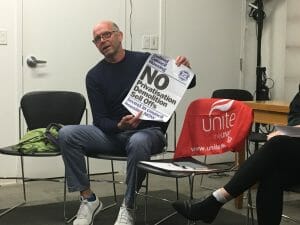

Glyn Robbins, author of “There’s No Place: The American Housing Crisis and What It Means for the UK.” Photo courtesy of Tanner Howard

Near the beginning of his time as a housing organizer and worker, U.K. activist Glyn Robbins came to the United States to intern at the Jersey City Public Housing Authority. The year was 1992, the same year that HUD’s HOPE VI program made the destruction of public housing a nationwide trend, and Jersey City was in the midst of destroying thousands of housing units. While the wholesale destruction of public housing in the U.S. was just picking up steam, the thought of such a path for U.K. housing policy seemed impossible at the time.

“At that point, it seemed like what I’m saying now would be ridiculous,” Robbins said. “But today I’m afraid it doesn’t, and it seems like something that’s likely unless we change direction.”

That experience, and Robbin’s observations of similar trends in his home country, kept him busy organizing on both sides of the Atlantic. Finally, last June, he published There’s No Place: The American Housing Crisis and What it Means for the UK, arguing that housing campaigners in England could learn from America’s failures as their government pursued aggressive reforms to the country’s stock of non-market housing.

Two days after its release, Grenfell Tower, a council estate in Kensington, London’s wealthiest borough, went up in flames. The fire spread from a single apartment through the entire building, which was not equipped with fire sprinklers. The building was clad in combustible material, plastic-filled aluminum panels and synthetic insulation, that was found to be 14 times above the combustibility limit. Although residents had repeatedly raised safety concerns during and after renovations in 2015 and 2016, their prediction that “only a catastrophic event will expose the ineptitude and incompetence of our landlord” became a sickening reality last June.

A year later, and Robbins isn’t exactly sure what to make of what happened. As the government finally begins its formal inquiry into the tragedy, one that saw the death of 72 people, Robbins wants to believe that the event will be a catalyst for reimagining housing policy, to honor those deaths by rebuilding robust, extensive council housing (similar to U.S. public housing, but far more extensive and available to people at all income levels) in the U.K. Still, as architecture firms begin to imagine redeveloping the rest of the London Lancaster West Estate, a specific council housing site where the tower is located, Robbins knows that organizers and residents will have to fight if their vision for social housing will pass.

“Grenfell is an incredibly lucrative site in the eyes of property developers, so we just cannot take for granted that their tears about the victims are not crocodile tears,” he said.

While the pressures of property development threaten to erode the memory of this tragedy, the people aren’t willing to forget. On the 14th of every month, a diverse group of local residents, housing campaigners, faith organizations, trade unions, and the bereaved gather for a silent walk around the neighborhood. Robbins says the event has become “essential” to preserving the memory of those lost, and that the “usual chatter and chanting of public demonstrations is replaced with a mood of reflection, heightened by the fact that we are in the midst of a busy metropolis and that we’re walking through the same streets that the victims knew.”

Shelterforce asked Robbins what led him to view U.K. and U.S. housing policy as intertwined, how public protest stifled the Conservative Party’s 2016 Housing Act, and what’s changed in the wake of Grenfell.

Tanner Howard: In the book, you describe the striking interconnections between U.S. and U.K. housing policy, both rooted in similar strands of paternalism at the start of the 20th century. Although the two nations had quite different experiences as the century wore on, why did you again turn to the U.S. to try and understand where your country is headed?

Glyn Robbins: We’ve now reached this critical convergence, and really, I suppose the reason why it’s important to me as a campaigner and a worker is that [the U.S. experience] is a warning. It sounds a bit melodramatic in some ways, but I do often say to people, “Unless we fight, what’s left of non-market in the U.K., and especially council housing, is very rapidly going to arrive at a U.S. model.” There’s an emergency from the U.K. perspective.

We are, almost by the day, seeing more threats to council housing, and when I think of it from a historic perspective, when I think about being in Jersey City in 1992, only 26 years ago, the thought that the U.K. would be in a position whereby you could make comparisons with U.S. public housing was really unthinkable.

In the book, you describe the Conservative Party’s 2016 Housing Act as one of the biggest threats to non-market housing. What was its impact? How have council housing proponents responded?

When activists and workers became aware of the legislation, it really was a sort of wake up call. From my point of view, it was a confirmation of my convergence theory, because within the Housing Act, I saw the government attempt to drive the final nail into council housing.

The thing that really stood out, and which mobilized a lot of opposition, was the introduction of means-testing, which I know isn’t very counter-intuitive in the U.S., but it’s never had a base in this country. Council housing was created, developed, and for most of its life has been available to anybody who needed it, irrespective of income. The Housing and Planning Act wanted to change that, and this was a real threat. It was a direct, material threat to council tenants who were earning a relatively modest amount.

For instance, on the estate where I work, I knew of a family who had two earners. Neither of them were earning much more than the minimum wage, but their combined income took them over the threshold, and so their rent would have gone up by at least 15 percent. It really was a very stark issue, and it’s what got the campaign going.

David Cameron made it very clear when he said that he wanted council housing to be emergency, temporary housing. So beyond it being this economic threat, it was an attack on the concept of council housing itself. When my grandparents moved from slum housing in the East End, to a council house, they said to their dying day that it was the best thing that ever happened to them, and they lived there for the rest of their lives. My dad was born in 1929 to the sort of Great Depression squalor, and then moved into a council estate, completely transforming his life. I feel that I’ve benefited from that, indirectly, even though I wasn’t the one that moved out of a slum into a house with an indoor toilet and a front and back garden.

Through a broad-based campaign, we’ve rendered the act to a state of suspended animation. None of the significant threats that we were worried about have yet quite materialized. But as long as it’s law, it remains a threat, so if the political climate changes, this becomes a more urgent issue. For the moment at least, that campaign managed to push back on it, so the worst aspects of the act have not been fully implemented. We proved again, if ever we have to be reminded, that when we combine the forces of trade unions, tenants, activists, and others, we aren’t powerless in this, and we have effectively put a hold in what was the government’s flagship housing policy.

How did those fighting for social housing in the U.K. respond to the Grenfell tragedy?

I still find it hard myself, and obviously I am somewhat removed from the immediate trauma of Grenfell, but myself and others do feel still shocked that this could happen, that we’ve reached this point. This is the thing we’ve been fighting to prevent for years, and that such an incident could take place has given us all pause for reflection. At many, many levels, that trauma is still gestating and working its way through, and certainly there is a palpable sense of community trauma, including people that were not directly affected. There’s this real sense of shock and outrage that’s quite difficult to describe.

The public inquiry is going through its first significant stages at the moment, and within the first week, we’re already hearing, day by day, another piece of outrageous evidence, or examples of the degree of negligence and culpability for what happened within the establishment. They created a death trap, literally. Had they wanted to incinerate these people alive, they couldn’t have done a better job of it than what actually happened, in terms of the cladding materials that were selected, the complete disregard for safety, and the promotion of profit over people’s lives on a shocking scale.

I remember, as soon as I’d realized what had happened, writing on Facebook, saying, “It will come out, in due course, that these people have been killed because profit has been put before people,” and it looks very clear that that’s what the inquiry is going to lead toward now. To what extent that puts the blame where it actually needs to go, I have my doubts, and clearly what’s going on in the moment is this massive blame-shifting, including to the firefighters who first responded to the blaze.

If Grenfell was a turning point in the U.K. around housing issues, where do you see the country going from here?

I think we have to inject a note of caution, perhaps, because, as I wrote about in The Guardian, we’re talking about this as a turning point, and it absolutely has to be. But we have to remember that turning points can go either way. I don’t think we can necessarily assume that the Grenfell turning point will lead in the right direction. There is an argument saying, “This is the final proof, council housing doesn’t work, Cabrini Green-type high rises don’t work.” There’s a whole load of stereotyped arguments that can be used here to further undermine council housing. So as much as I’d like to say that nothing’s going to be the same again, everyone is going to learn the lessons, I don’t think we can say that with real confidence, and I think a lot of it depends on the amount that we can maintain campaign pressure and insist that the people ultimately responsible for this don’t get away with it.

The Labour Party clearly, and Jeremy Corbyn in particular, have had a much more genuinely compassionate response. He connected after Grenfell in a way that Theresa May could only dream about. Corbyn is someone who grassroots campaigners have known for decades. He has a long and honorable record on the housing question, so he doesn’t have to manufacture a synthetic sympathy for council housing. His record speaks for itself on this question.

A few weeks ago, the Labor Party produced a green paper around housing, and Corbyn’s written the foreword, and says, quite rightly, that Grenfell is the symbol of our housing policy failure. That’s absolutely the right way to put it. But then you read through the document, you realize that there are again some causes for concern, in terms of what kinds of policies the Labour Party is proposing around housing. I’m concerned that they are still somewhat enthralled to the private developer model, the inclusionary zoning type model, in the way that [Mayor Bill] de Blasio is doing it in New York. I would like to say that Grenfell is the moment when we realized that we need to reinvest in council housing in every sense of the word, but actually what’s said in that Labour Party document indicates that they’re not quite on the same page as us from that point of view.

I guess I’m saying it’s a bit early to say what the long-term impacts of Grenfell are going to be, and in the end it’s quite easy to go to ceremonies, offer sympathy, and all of that, but is it going to change anything in policy terms? In the moment, we can’t be sure of that. There won’t be genuine justice for Grenfell, as one of the campaigns is called. What that really means is not plaques on the wall, it’s not naming stuff. It’s rebuilding our housing policy in a way that truly honors those people, by improving safety, but going beyond that and thinking about housing, not as a commodity but as a public asset.

I was hesitant to make the comparison at first, but the more I think about it, and although the scale and circumstances are different, I don’t think it’s impossible to imagine Grenfell having the kind of outcome that’s not dissimilar to Katrina in New Orleans, and the whole disaster capitalism model, using this disaster as another way of attacking non-market housing. We know how politicians like Representative Jim Baker reacted to New Orleans, saying, “We finally cleaned up public housing in New Orleans. We couldn’t do it. But God did.” Politicians in this country aren’t, generally speaking, quite as crude as that, but some of them will be thinking it, and we need to remember that Grenfell is still in the wealthiest borough in the country, with a property market all around it that’s massively overheated. That threat is still out there.

Thanks for this, Tanner. I’m reading it (through jet-lag!) having just arrived in DC for the annual conference of the National Alliance of HUD Tenants (NAHT), which I attend most years. I come here to find inspiration from US tenants and housing activists. The issues you’ve picked out in the interview are a stark reminder of what’s at stake – especially when I think about the bloke sleeping about six blocks away, dreaming of the whole world as ‘real estate’. Forward with our values, not his!

Thank you Shelterforce and Tanner Howard for your interview with Glyn Robbins. During the coming fall term I will be teaching a course covering landlord-tenant law at Seton Hall Law School. I intend to touch upon the danger of treating affordable housing as a commodity rather than a national resource. The interview with Glyn Robbins and the tragedy of the fire at Grenfell in London is an important object lesson for students. This is especially true in light of Mr. Robbins’ early observations about the tear down of public housing units in Jersey City in the early 1990s and the disturbing trend for affordable housing movements in other nations.