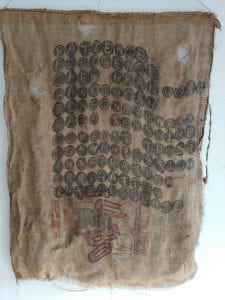

Wormfarm Words, by Wormfarm resident artist Hannah Smith. Photo courtesy of Wormfarm Institute

The real food or local food movement has been critiqued as having two sets of implications: One fosters good jobs, boosts a sustainable economy, supports farms, reconnects people to the land, and creates access to healthy foods for people who didn’t have it before. The other fosters an elite, expensive version of food that appropriates cultural traditions and takes them out of reach of those who grew up on them (see: kale, collards), shames people who don’t have time to cook from scratch or money to buy artisanal cheese, and generally leaves a lot of people out.

So how do we engage with this supposed dichotomy and try to tip their scales toward the former? The first thing may be to recognize that it’s not so much a dichotomy but a spectrum.

Though I live and work on a small farm in rural Wisconsin and grow organic vegetables, I was formed by cities and raised on TV dinners and still occasionally use the drive-thru of my local burger franchise. My food system discoveries came later in life, are sometimes more sensual than virtuous, and continually evolving.

More than 20 growing seasons have made a farmer of me, though no less an artist—also a spectrum. In these dual roles, I live along a rural/urban continuum which ideally supports a flow of not only goods and services, but value and values. What I witness and live suggests that dichotomies are insufficient models, where very little is pure and undiluted.

For several years I worked for and learned at Growing Power Inc., an urban farming nonprofit in Milwaukee. We grew acres of high-value microgreens to support Growing Power’s low-cost community-supported agriculture (CSA) program. Lessons on growing microgreens were offered as part of its weekend training sessions and it is where I learned that the question of an equitable food system was not a simple “either/or” proposition.

Everybody Eats

A healthy and just food system must necessarily accommodate the broadest range of constituencies. This begins by connecting as many people as possible to productive land and good food, and tightening up the food chain to make the links in that chain tangible.

Knowing the provenance of one’s food is a critical step in developing an appreciation and value for the work that goes into bringing it to the table. That food might be grown in one’s yard, simply prepared and shared with family, or it could be transformed into high-value artisanal products and sold.

While a goal of a sustainable food system should be to ensure that all people have access to sufficient, healthy, and culturally appropriate food, it should also work to cultivate an appreciation for those who produce it and adequately compensate them. Sustainability is about thriving, not just surviving. We will not thrive if we are poorly paid martyrs to a good cause; and thus, in a healthy, diverse, and vital food system, some of our efforts might need to be directed to those who can pay $9 for a jar of pickles.

Urban agriculture and community gardens are important pieces in a just food system. Widely dispersed, small-scale, hyper-local food production provides fresh produce to places perhaps not served by greengrocers and farmers markets. They offer the opportunity to experience the challenges and rewards of eating what you grow. Beyond the direct benefit of having fresh produce, there are collateral ones in being outdoors with hands in soil, learning to pay attention to the myriad factors that influence how those plants do or don’t grow, and finally understanding that there are things that remain out of your control. These are valuable lessons that can serve all of us.

The Undeniable Value of Agriculture

Once one has become moderately adept at growing food, there are just a few steps to marketing what you grow, to exchange the literal fruits of one’s labor for goods, services, or money. This is where gardening turns into agriculture. Bury a handful of seeds in moderately fertile soil, add sun, rain, time, and attention and the results are a fungible asset that every one of us requires every day. This is the most basic economy and one that has supported human existence for the last 10,000 years.

Agriculture creates basic value. There are many different ways to benefit from it—from being a producer and selling fruit and vegetables at a farmers market to preparing or processing raw ingredients in a way that adds value and extends shelf life.

A $9 jar of pickles could be an indicator of an imbalanced system, but if you look a little closer, other factors may come into focus. Suppose the purveyor of the pickles was a trained chef who, for over two decades, had committed to purchasing directly from growers and paying fair to premium prices. And perhaps those pickles were processed in a shared commercial kitchen where the chef was one of half dozen entrepreneurs using it to support their human-scale food businesses. And what if those entrepreneurs hosted a program that employed underserved members of their community, teaching valuable kitchen skills and assisting with placements in the local food industry? And finally suppose this artisanal pickle vendor was part of a cohort that worked to improve the food culture of their community by appearing at markets and special events demonstrating that skills, training, experience, and a unique personal vision can transform a humble curcubit into a valuable culinary and even aesthetic experience.

This all describes not a theoretical but an actual scenario with a chef we have worked with for over a decade whose support for a sustainable food system predates our interactions by twice that.

The whole idea of a food system is that it has these many interconnected and seemingly contradictory elements. A comprehensive approach to food system reform must address and attempt to reconcile the contradictions. One way is through farmer/ grower training that teaches soil building and pest control as well as marketing and developing techniques to add value and shelf life to what is grown.

While we must be wary of the exploiters and profiteers, we must also be catholic in our embrace of those who demonstrate how to leverage their skills, vision, and marketing savvy to create foodstuffs that warrant the term “artisanal.” They are blazing a trail through the moribund foodways of mainstream culture making success more possible for those who follow.

It’s true that the systemic inequities that plague almost every other aspect of our culture are also prevalent in the food system. But because food is fundamental, it is unique in its capacity to affect social, cultural, and economic development. Barriers that limit all of societies’ full participation will fall more readily in food system work than almost any other realm. And this is most likely to occur in a healthy food ecosystem—a complex polyculture that acknowledges the ennobling work of the few who feed the many and rewards their efforts.

“Culturally appropriate” foods? It’s possible to take this too far. My grandmother’s foods would be culturally appropriate for me, and many of them retain emotional significance for me and my family. But she had no fresh vegetables from November to June, she ate way too much animal fat (chiefly lard), and no whole grains at all. So we eat somewhat differently, but with respect for where we came from. And, collards and kale have not become expensive at all!

From the standpoint of producer/retailer, the $9 jar of pickles may not be an “imbalanced” or “immoral” act, as pointed out.

From the standpoint of a society that promotes such huge gaps in wealth, it is.

From the standpoint of a consumer who can afford such “artisanal” food–even when that consumer might be scrupulous as to choose a product built on such a solid social platform–by demanding reciprocity in order to participate in that system, they are negating the goodwill of their act. They should just be giving to the farmer freely, and eating the same food everyone else does.

The pickles, if made correctly, are an extremely healthy food, and should be made just as affordably available to everyone. The farm producing the expensive product is creating scarcity, at least the perception thereof, just so that the wealthy consumer can feel special and will be encouraged to participate. When artisanal, hyper-local foods are no longer trendy, the business will die–bc in order for these things to survive long-term, as they need to, we actually need to sell the moral obligation; people’s hearts need to change. Capitalism doesn’t work in the long-run.

Culturally Appropriate food?!!

I’m not quite sure what that means in this context. Certainly there are times when one should be sensitive to to the cultural familiarity and comfort of foods, such as offering the children of undocumented workers in US custody tortillas rather than toast.