Photo by American Advisors Group, via flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0

Last week, the Senate introduced its proposal for tax reform, while the House Ways & Means Committee debated and passed its own version. Talk of tax reform has reached a fever pitch in Washington, D.C., and corporate C-suites, but most Americans may not realize just how high the stakes are and what impact the final legislation could have on their own financial security for years to come.

When most people think of tax reform, they just want to know if they will pay more or less. But taxes are about much more than just how much the government takes out of your paycheck. The tax code is also used to subsidize the various ways Americans build wealth, in important areas like higher education, retirement, and homeownership. These wealth-building provisions of the tax code cost the federal government nearly $700 billion annually.

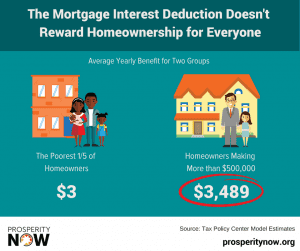

The biggest single source of wealth for most Americans is their homes, and the Mortgage Interest Deduction is one of the largest sources of spending on housing and homeownership. In 2014, the Mortgage Interest Deduction cost the treasury more than $70 billion. In contrast, the entire Housing & Urban Development budget for 2017 was just under $44 billion.

For that much money, you would think that the Mortgage Interest Deduction would be a huge driver for homeownership and support for the middle class, but neither is true. The deduction has not been found to increase homeownership rates; it simply encourages existing homeowners to take on more debt. Research has also found that the Mortgage Interest Deduction artificially raises the price of homes in some areas, making homeownership less affordable than it would be otherwise.

If that wasn’t bad enough, the vast majority of this $70 billion in spending each year goes

So the case for reform is a slam dunk then, right? Well, not if you’re the Senate. In its current proposal, the status quo would prevail for the Mortgage Interest Deduction. The House proposal, however, would cap the Mortgage Interest Deduction at $500,000 for any new mortgages. Only six percent of new mortgages originated in 2012-2014 were for loans exceeding $500,000. Even so, this cap could save $300 billion over 10 years, according to the Tax Foundation.

Indeed, $300 billion is a lot of money—money that could be used to improve housing affordability for millions of low- and moderate-income families. But here is where the House tax reform plan goes wrong: instead of redirecting this money to promote homeownership and help solve a nationwide housing affordability crisis, the House tax reform bill would give that $300 billion back to corporations and the ultra-wealthy in the form of tax cuts.

This “reform” to the Mortgage Interest Deduction is part of a larger pattern in the House tax reform bill. The proposal looks to eliminate or scale back tax breaks or expenditures, many of which disproportionally benefit the wealthy or special interests, which is not necessarily a bad thing. Upside-down tax benefits of this type include those for retirement accounts, higher education savings accounts and tax breaks, the State and Local Income Tax deduction, and the granddaddy of them all, the Mortgage Interest Deduction.

But instead of using this $300 billion to make the wealthy even wealthier, Congress should turn this tax spending right-side up and use it to make housing more affordable for the most vulnerable and to make homeownership a reality for more families.

Congress could start by turning the Mortgage Interest Deduction into a more equitable credit, so more families could access and benefit from it. Congress could also divide up that money and create new credits to help low- and moderate-income families pay their rent and save for a downpayment on a home. Congress could even bring back the temporary first-time homebuyers tax credit from the American Recovery & Reinvestment Act. Such a move would surely help families with closing costs on their first homes as it did the first time, but of course, any progress championed by then-President Obama is a nonstarter in the current Congress.

Tax reform is a once-in-a-generation opportunity and one of our best tools for turning the tide against rising economic inequality. The House and Senate proposals would supercharge inequality at a time when we need true reform to the tax code. And what better place to start than at home, where we have a clear opportunity to make housing more affordable for those who need it most—a far better option than more tax cuts for the ultra-wealthy and corporations.

Instead of an arbitrary figure (ultimately settled on as $750,000 for married persons filing jointly) and not being indexed for inflation or to address changes in home prices, the mortgage debt cap for the mortgage interest deduction should have been keyed off the “”high-cost”” conforming loan limits used by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. For 2018, this would mean interest in mortgage amounts of up to $679,650 could be deducted, and the figure would change each year. This would cover the vast majority of Americans.

Could more funds have been earmarked for affordable housing and housing support programs? Of course. Changing the deduction to a credit has also been kicked around for a number of years now, but it seems unlikely that this change will ever occur.

It’s not clear if “”the wealthy”” will benefit from the change to the tax code or not; time and changing behaviors may ultimately determine this. However, it could be said that the changes to the MID and the cap on state and local taxes (SALT) will penalize at least certain wealthier borrowers, as these changes will mean increasing tax bills for borrowers in places where homes are most expensive and local property tax bills the highest — New York and California, just to name two.