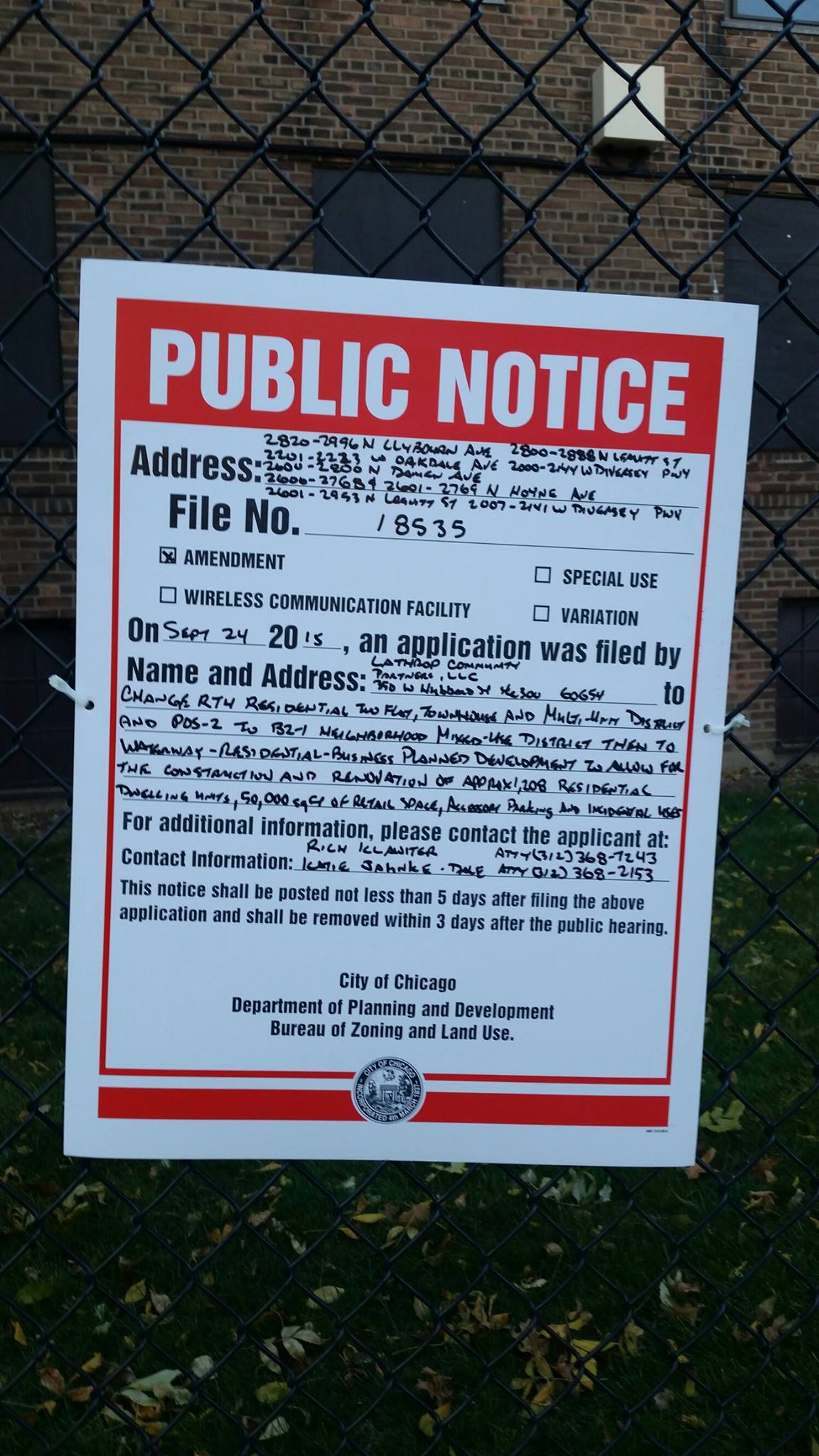

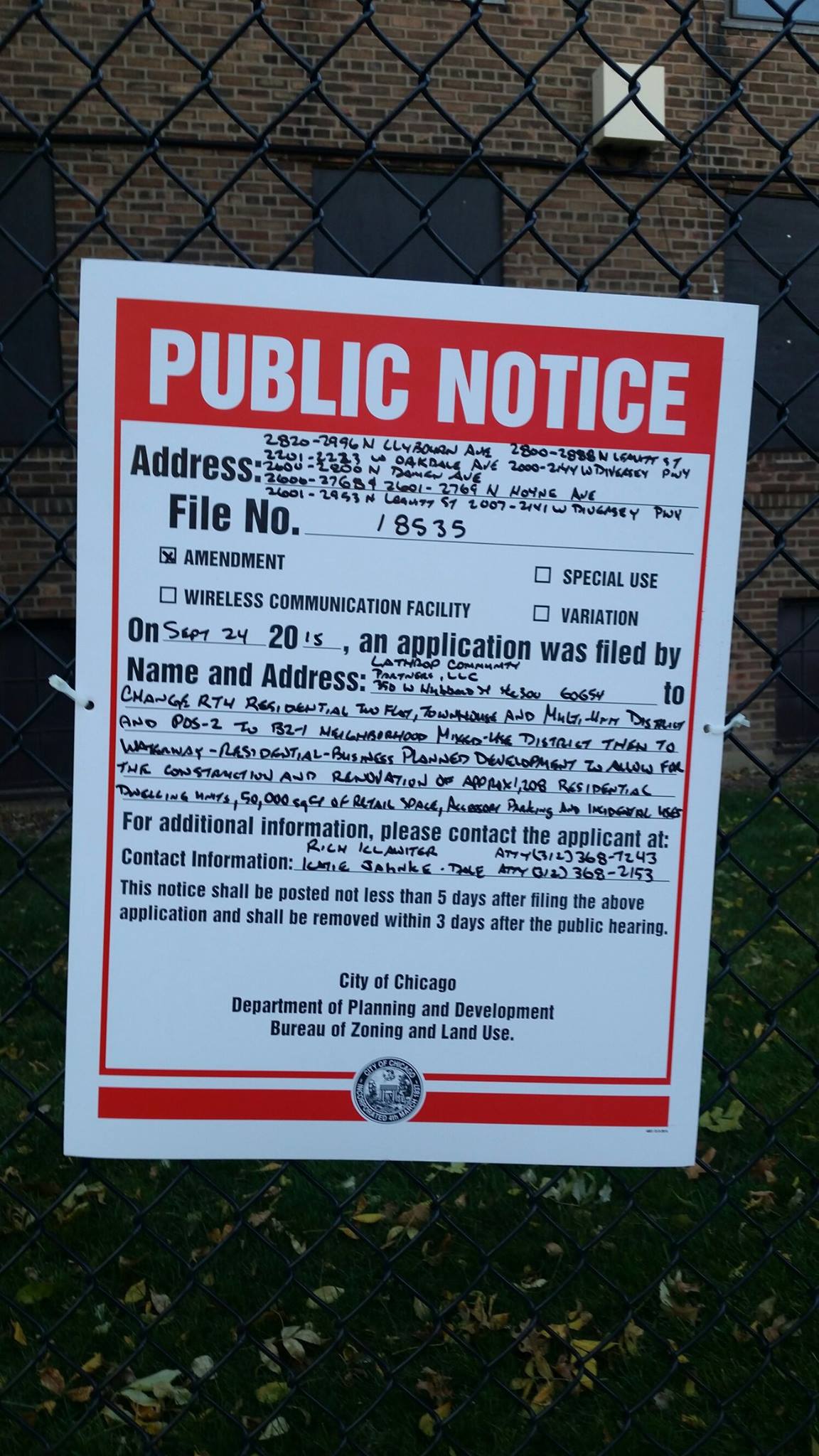

This zoning change notice was the latest in a long series of moves to disperse public housing communities in Chicago.

Signs like the one above went up at Chicago’s Lathrop Homes a few Fridays ago. In 1999, the Chicago Housing Authority, in step with other housing authorities throughout the country, began a plan to demolish and/or rebuild a grand majority of their housing stock throughout the city. The result of this Plan for Transformation was the demolition of 51 of their 52 high-rise public housing buildings. Among the buildings demolished were some of the most infamous of Chicago Public Housing, including but not limited to: the Robert Taylor Homes, Ida B. Wells Homes, and the Cabrini-Green Homes.

The Lathrop Homes are a series of two-, three- and four-story homes that were built in 1938, and are one of the first public housing developments built in Chicago. As a result, the Lathrop Homes were placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2012. Preserve Lathrop Homes has been advocating for their preservation since 1999. Unlike many of the advocacy groups for many of Chicago’s public housing developments, Preserve Lathrop Homes has so far been successful in keeping the demolition/rebuilding of the Lathrop Homes at bay.

Personal Effects of Redevelopment

In 2011–2012 I spent a year talking to residents and activists who lived in Chicago Public Housing about their experiences living in CHA housing developments during the Plan for Transformation. While their narratives were varied (many didn’t know what the Plan for Transformation was), many, if not most, spoke to the impact that the demolitions of building after building had on their intimate, social, and political lives.

The central narrative around the plan was that the old Chicago public housing policy design facilitated concentrated pockets of poverty that “exacerbated the problems of unemployment, substance abuse and crime.” As such, advocates of the new policy argued that the plan would allow for a transition from clumping poor residents together in high-rise buildings, to instead integrating them into mixed income neighborhoods.

Most significantly, despite the vilification of housing project spaces that justified this multi-million dollar project, the plan still called for one of every ten CHA residents to be housed in a housing project on the city limits called Altgeld Gardens.

Media and policy makers emphasized that the high-rise public housing model was the cause of crime, drug-use, and unemployment among people living below the poverty line. They emphasized that poor people living among other poor people only exacerbated poverty, but the problem with this narrative is that it failed to see the residents of these communities as human beings. It fell into the sloppy habit of seeing poor black women (black women make up the majority of the residents serviced by the Chicago Housing Authority, eighty-four percent), as objects that simply give birth to crime, disorder, and national welfare debt, to be managed and moved around.

Political Communities

In reality, these communities were made up of individual residents who’d made these public housing developments their homes; the people who lived next door were neighbors and friends. These communities were also political blocks. Every public housing development had an elected local advisory council that not only worked to ensure things functioned normally within the development, but also advocated for residents city-wide at Chicago Housing Authority Board meetings and in front of the wider public. These local advisory councils often conducted voter registration throughout their neighborhoods and made sure residents showed up on voting day, during presidential elections and during off-years. Long-time members of various local advisory councils were also sometimes voted to two of the resident positions on the Chicago Housing Authority Executive Board.

With the demolition of the 51 high-rise buildings in Chicago, these residential, social, and political communities were destroyed right along with the buildings themselves. Now that these residents are spread throughout (and outside of) the city, what little political power they had has been destroyed. Their ability to advocate for themselves and access the many bureaucracies in order to receive social welfare provisions has been stymied as a result of their placement in neighborhoods far from the city’s core.

So what’s the bottom line? As housing authorities throughout the country continue to blame public housing for the existence of crime (as opposed to rampant unemployment, poverty and institutional racism), it’s time that they begin to consider the personal impact destroying it will have on the people who live there.

Photo credit: photo 1, courtesy of Alexandra Moffitt-Bateau; photo 2, Julia C. Lathrop Homes, by David Wilson via flickr, CC BY 2.0)

Comments