At the height of the pre-2008 housing bubble, America’s largest banks were engaged in such a frenzy of trading mortgage-backed securities that they lost track of the true owners of millions of homes. As the economy collapsed, banks sought to cover this up and to speed foreclosures on millions of Americans who had fallen behind on mortgage payments by falsifying documents on a massive scale.

This had catastrophic consequences. At least 2.7 million households that had entered mortgages from 2004 to 2008 lost their homes to foreclosure by February 2011, according the Center for Responsible Lending, with African-

American and Latino borrowers twice as likely as whites to lose their homes or fall into serious delinquency.

But while most states have struggled to turn the tide — and the National Mortgage Settlement seems to have left no one fully satisfied — an organizing drive in Hawaii has quickly generated concrete results.

Common Stories

In 2010, Hawaii was suffering from the ninth-highest foreclosure rate in the country. Throughout the 41 faith congregations and allied community groups who were members of Hawaii’s Faith Action for Community Equity, a faith-based organizing group affiliated with the Gamaliel network, families were struggling to hold onto their homes.

One of them was Honolulu resident Melba Amaral. Amaral and her husband ran into difficulty making mortgage payments after her husband was injured in a car accident and lost work hours and benefits. Amaral ran a childcare center in their home, meaning a loss of the house would shutter her business as well.

“I had an obligation to let my clients know two months in advance if the center would have to close,” Amaral said. “We have a daughter in high school. We were terrified.”

For more than a year leading up to that point in late 2010, Amaral and her husband had sought a loan modification from Bank of America. “It was a nightmare. We would FedEx all our documents to one Bank of America office, then we’d get a request from a different office asking for identical information,” she said.

After the Amarals had corresponded with 11 different Bank of America offices on the mainland, “they eventually said we failed to qualify. We had to come up with $20,000. The representative told my husband, ‘Why don’t you go borrow it from your friends and family and call us back?’”

FACE director Drew Astolfi had heard stories of struggles like the Amarals’ from across the state. He and FACE organizer Kim Harman decided to conduct a statewide study on foreclosures as the first step of an organizing campaign. Their research showed that the Amarals’ case was hardly unique.

“We found that 97.5 percent of the foreclosures were being driven by the big banks on the mainland” such as Bank of America and Wells Fargo, said Harman. “Local banks were very careful because they knew the people they’d be foreclosing on. Most of the big banks didn’t even have loan offices on the islands.”

In addition to identifying the big banks as the real culprit, “the study surfaced leaders who were dealing with these issues,” Astolfi said. FACE had the core of a campaign; the next step was going public.

FACE planned a series of public events to build pressure on the big banks and galvanize support in the state legislature. The timing was right, as the legislature wanted to act, but had been “flooded” with contradictory anti-foreclosure bills during the 2010 legislative session, according to state Rep. Robert Herkes.

The Power of Speaking Out

But FACE had one major obstacle to a public campaign: the lack of a public voice.

“Getting people to come forward is not easy,” says the Rev. Bob Nakata, former president of FACE Oahu. “People want to meet their obligations — especially financial — and they’re embarrassed when they can’t do that. One of the most powerful weapons on the other side is shame and stigmatization.”

Nakata said that clergy were in a unique position to reassure people that their financial struggles were not a moral failure: “That’s why it’s important that a faith-based organization took this on. Pastors have a little more credibility than most in saying, ‘It’s not your fault. It’s the system that failed.’”

Amaral was wrestling with her own feelings of shame, isolation, and anger when Harman, the FACE organizer, called. Harman was looking for a community member who could share a powerful personal story at the campaign launch on December 10, 2010. She had heard about Amaral’s struggle from another FACE leader.

At first, Amaral was hesitant to open up. “I thought, ‘Should I tell her?’ I feared the scrutiny and the name-calling. I was afraid my childcare clients would go into panic mode,” Amaral said. “But something was telling me, ‘Talk to her.’ We were on the phone for about five hours after that.”

“In the end, I decided I was ready to fight,” Amaral said. She added that her clients were so supportive that they encouraged her to bring their children with her when she joined other FACE members in testifying at the State Capitol.

Amaral’s testimony brought forth a flood of support and inspired even more FACE members to come forward. Leaders were working every day, testifying at actions, going to legislative hearings, and raising awareness. As a result, the state legislature formed a Foreclosure Task Force, which drafted a 15-page bill that ultimately ballooned to 100 pages as FACE members testified.

The bill included the requirement that lenders sit down face-to-face with homeowners for mediation before foreclosing. It also placed a temporary moratorium on all new non-judicial foreclosures, and raised standards for lenders to show that they truly had the right to foreclose.

One source of the crisis, Rep. Herkes noted, was that the big banks “had retained mortgage servicers who got a commission on foreclosures,” he said.

“Foreclosure doesn’t only affect one family: it affects the whole community,” Amaral said. “The bankers and the lobbyists fighting the bill had to see that.”

As momentum grew in the legislature, FACE kept the public pressure up with a series of public demonstrations — a total of six on three islands — demanding that the big banks meet face-to-face with homeowners facing foreclosure. The public events “were the muscle of the campaign,” said FACE’s Harman. “They created tension, got media coverage, and forced the banks to the table.”

In March 2011, Bank of America representatives sat down with FACE and offered settlements to several dozen of the group’s members, including Amaral. “I got the settlement packet and showed it to an attorney friend. She said it was one of the best deals she had ever seen,” Amaral said.

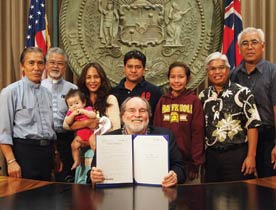

That May, Gov. Neil Abercrombie signed the anti-foreclosure bill that FACE members had helped shape. In terms of protections for homeowners, it was “the strongest thing imaginable,” MSNBC commentator and mortgage expert Martin Andelman told Honolulu’s Civil Beat.

The new law, called Act 48, gave owner-occupants of residential property in non-judicial foreclosure the ability to meet face-to-face with their lenders to modify their loans or work out a payment plan within three months. Banks were barred from carrying out non-judicial foreclosures without the face-to-face sit-down, and any previous foreclosure proceedings were frozen during the three-month process.

Foreclosures in Hawaii dropped by more than half from May 2011 to January 2012. “Personal bankruptcy rates plummeted, and the Council of State Governments recommended that every other state adopt a similar law,” says Rep. Herkes.

For Amaral and other FACE leaders, it was a triumph. “In the supermarket, a high school friend I hadn’t seen in almost 20 years came up to me and said, ‘Thank you! My sister saved her home because of you,’” Amaral said.

“It really put FACE on the map,” Nakata said. “When we started out, people said, ‘You’re going to take on Bank of America? Are you crazy?’ The win gave us a lot of credibility.”

When Hawaii joined the $25 billion mortgage fraud settlement deal in February 2012, Hawaii Director of Commerce and Consumer Affairs Keali’i Lopez called the deal “long overdue,” but noted that the state had not waited for the settlement to address Hawaii’s mortgage problems. Many of the key provisions in the settlement, Lopez said, were addressed last year with the Mortgage Foreclosure Dispute Resolution Program and with Act 48.

Harman said the most important result of the campaign was that it restored to thousands of Hawaiians something even more important than the ability to stay in their homes: their dignity. “These banks had set up a dehumanizing process,” Harman said. “The actions we held let homeowners talk directly to another person. The law lets them do that too. It was the dignity of the person that was being violated in the banks’ setup. We helped put an end to that.”

Comments