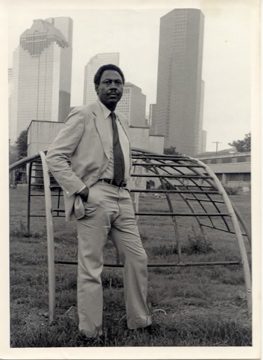

When Lenwood E. Johnson, the son of Texas sharecroppers, moved into Houston’s Allen Parkway Village project housing, the Freedmen’s Town section of the city had yet to be designated historic, and the village had yet to be saved. By the end of the 1990s the village was preserved, and Johnson proved to be something of an unlikely hero here in Houston’s fourth ward, historically one of the poorest sections of the city, but always ripe for redevelopment because of its proximity to the downtown.

Opened as San Felipe Courts in 1944, the 1,000-unit Allen Parkway Village (APV), whose namesake is the parkway named for Houston founders John and Augustus Allen, was the crown jewel of the Housing Authority of the City of Houston (HACH) and the largest one in the South. As APV aged, Houston property developers began eyeing the 37-and-a-half acres of prime inner-city real estate that it occupied — an area where freed slaves settled after the Civil War.

The developer’s lust for the land can be traced back to November 1977. HACH’s director Robert Wood crafted a letter proposing demolition to the Department of Housing and Urban Development claiming that the APV land values had escalated “beyond a cost where housing is the highest and best use.” In 1979 Houston Mayor Jim McConn’s Urban Policy Board blamed the state of public housing on the city’s lack of leadership, which they found “inexcusable in the midst of such wealth and well-being.” McConn’s board wrote that the city had no “central single focus for dealing with housing issues.”

Allen Parkway Village residents were given some hope that their decaying project would be rehabilitated when HUD authorized $10 million dollars to modernize it in 1979. Unfortunately, HACH failed to spend the money to revitalize the project. Congressional hearings held nearly 15 years after the HUD authorization revealed that roughly $8.6 million of the fund was untouched. Of the remaining $1.4 million, HACH had receipts documenting $700,000 used for repairs, but the rest of the cash disappeared. The remaining $8.6 million of the original $10 million from 1979 was used when the renovations began in 1996 (though the residents filed a Federal Injunction in 1991 that stopped the Housing Authority’s request to HUD to use the remaining $8.6 Million for other programs).

But long before that fact was disclosed, Johnson was continually bothered by the decaying condition of the housing project.

He began to organize.

Johnson became the mastermind organizer of the struggle to save APV. He always held the moral high ground because of Houston’s paucity of public housing.

The tenants elected Johnson as the president of the APV’s Residents Council in 1983. By 1984 the Houston City Council passed a resolution approving the HACH plan to raze APV. Local and regional HUD offices approved the plan in 1985.

During the fight Johnson used several tactics and strategies to stop the destruction of APV — strategies that included empowerment, education, coalition building, litigation, and legislation. Johnson told Shelterforce that his most important strategy was teaching the residents that they could gain the power to help themselves. After that, Johnson and his supporters were able to use the courts to stall the demolition. Lawsuits allowed the facts to become public information and kept the issue in the media. Once the residents got into federal court they could conduct discovery to produce facts that would support their cause, Johnson remembered. “Legislation was useful but without support from people it fails,” he said.

After Johnson organized the residents, he turned to non-residents including credentialed members of the community. Johnson’s allies convinced San Antonio U.S. Representative Henry B. Gonzalez, from Texas’ 20th District, to hold a Housing and Community Development subcommittee hearing in Houston about the proposed APV demolition. After the October 1985 hearing Gonzalez ordered the General Accounting Office to launch an investigation into the APV plan and a similar plan to raze public housing complexes in Dallas. Gonzalez also asked then-HUD Secretary Samuel Pierce to withhold a decision until more hearings could be held. Gonzalez’s actions stalled the city’s demolition plans.

Although the APV residents got Gonzalez on their side they could not get any support from their own Congressman, Mickey Leland, despite the fact that the public housing issue fit with Leland’s public persona as a champion of the poor. His record in Congress included co-sponsoring a bill that created the House Select Committee on Hunger. In 1985 he was elected to the chairmanship of the Congressional Black Caucus. He pushed for affirmative action in broadcasting, led initiatives that created the National Commission on Infant Mortality, and visited soup kitchens and homeless encampments.

But Leland, for his own reasons that, Johnson says, were in the interest of the property developers, did not champion the APV cause. Meeting requests made by the Coalition for Homeless of Houston and the Committee in Defense of Allen Parkway Village were also ignored.

Leland left himself politically vulnerable by not taking up the APV cause. His inaction on the controversy did not square with his activist reputation and legislative record and many of the APV residents who faced displacement were African American, as were Leland and Johnson. In addition, APV sat in the most historic black neighborhood in Houston, which left Leland vulnerable to attacks by Johnson and his surrogates. Leland had spoken about the homeless issue, yet here, in his own district, were residents facing the threat of eviction and homelessness.

Johnson came up with a tactic that pressured Leland to act. It would prove to be the most important turning point in the campaign to save APV recalled Joan Dinkler, an important APV ally and founder of the Houston Housing Concern (HHC). Dinkler and HHC recruited over 100 churches to sign on to a resolution to save APV.

Johnson recruited Peter J. Riga, a lawyer and a former Catholic priest to write an editorial. On August 7, 1987 The Houston Post published Riga’s editorial, titled “Allen Parkway Village: Whose Fault?” and subtitled “Officials at all levels seem determined to disperse needy residents.” Riga described two factors that were working overwhelmingly against the residents. He wrote that elected officials were cooperating with developers’ interests and that there were few resources allocated to renovate APV. Further, Riga contended that the renovation funds had been cut off long ago in an effort to push out residents and that the housing authority had been working with other city officials to disperse the poor. Finally, Riga noted that there were about 20,000 families on the waiting list for public housing in Houston and highlighted the moral injustice of developers pushing public housing tenants off the land.

The letter worked. Twelve days after Riga’s editorial, The Houston Post published an editorial by Leland titled “Housing for Poor Has a Long Way to Go” and subtitled “Allen Parkway Village reflects administration’s failure to develop policy. He pointed to a 71-percent decline in the federal budget for low-income housing since 1981 and wrote that it was inappropriate to demolish APV when there were thousands on the waiting list for public housing. Leland mentioned Lenwood Johnson’s name twice.

Suddenly, Leland was in the APV tenants’ corner. Johnson pushed him to introduce legislation to benefit APV residents. Rep. Gonzalez wrote an amendment that Leland introduced. Leland and U.S. Rep. Martin Frost of Dallas got the amendment added on to an appropriations act in 1987. Frost had similar public housing concerns in his district.

After some legislative triumphs and setbacks, including Leland’s untimely death in a plane crash in Ethiopia in 1988, APV residents in 1996 finally signed an agreement, with then-HUD Secretary Henry Cisneros that provided $36 million from HUD’s Office of Distressed and Troubled Housing Recovery for the renovation of APV. The final result was that 300 of the 1,000 units named to the National Register of Historic Places were saved and renovated. Another 200 units were built, for a total of 500 units on the site. One hundred more units were constructed in Freedmen’s Town. While the residents were short 400 units, the larger win was that not one inch of the land was transferred to private developers.

Because of the organized effort initiated by Johnson, we saw how the Houston City Council, first voting to demolish APV, later had to backtrack when they saw that the public would not support their actions. The government entities never sought a public consensus or the tenants input before their demolition campaign. Public housing tenants and activists can learn that organizing is the key to getting their voices heard and getting a place at the negotiating table. It shouldn’t sound like, nor should we allow it to be a cliché when we read about residents taking on City Hall and winning.

As for Lenwood Johnson, he’s still involved in organizing and inspiring younger people to be involved in social justice struggles.

Comments