In California, municipalities are required by law to plan for their fair share of affordable housing. Has this put housing advocates out of a job? Not quite. There’s a big difference between a general state mandate and solving the housing crisis. But the requirement has provided a way for Bay Area housing activists to get their issues on the table – and a means of applying some pressure to recalcitrant municipalities.

The mandate works like this: All cities and counties in California must have a general plan that includes a housing plan – known as the “housing element.” The general plan serves as the local constitution for land use and development. Once adopted, it has the force of law – a local government cannot legally act inconsistently with its general plan.

Housing elements must be updated every five years. First, the regional council of governments allocates to each city and county a number of new housing units that it must plan for, broken down into four income categories from “very low” to “above moderate.” In the Bay Area, for example, a quarter of a million new homes are needed by 2006. While the law does not require cities and counties to build these new homes themselves, their housing elements must:

- Establish housing programs and policies – from rent control to funding affordable housing developers – that encourage affordable housing for people of all incomes and those with special needs.

- Demonstrate that they have enough land zoned for multifamily housing to build all of the homes needed for lower-income families.

- Reduce obstacles to housing development, such as density limits, excessive requirements for parking spaces, even community opposition.

- Describe how they will use available funding for affordable housing.

Plans must be certified by the state, which can require changes if they don’t comply with state mandates.

Updated plans for Bay Area cities were due at the end of 2001. Seeing the revision process as an opportunity to get good housing measures on the table, the Nine County Housing Advocacy Network and the Greenbelt Alliance launched the Fair Share Housing Campaign. The campaign’s goals are threefold:

- Educate cities and citizens about workable solutions to the affordable housing shortage (and, especially, show cities that haven’t built enough affordable housing how other cities have been more successful).

- Get these proven strategies into cities’ housing elements, where they become enforceable commitments.

- Get more people and more organizations involved in housing advocacy locally and regionally for the long term.

The housing element updates provided area housing advocates with numerous opportunities to talk about housing and suggest solutions. There were local hearings in Dublin, for example, at which members of the Tri-Valley Interfaith Poverty Forum testified, relating stories of lifelong area residents unable to afford a place to rent, much less buy. In response, the Dublin City Council has greatly strengthened its inclusionary housing ordinance.

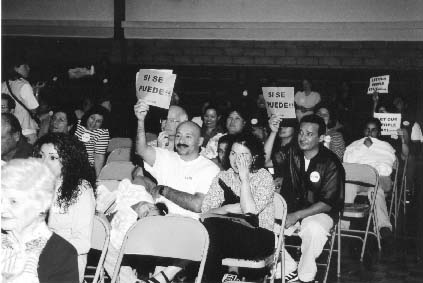

|

| Members of Congregations Organizing for Renewal in California rally for better housing commitments from their local governments. Now they must keep the pressure on to make sure promises are kept. Photo by Oscar Iraheta. |

Getting local governments to act wasn’t always that easy, of course. The campaign adopted many traditional organizing tactics, from research to direct action. In Concord, many people live in run-down apartments, and the affordable housing built in the last decade met only 3 percent of the need. Meanwhile, the city was spending scarce housing dollars on items such as sidewalk repairs. So the Contra Costa Interfaith Supporting Community Organization (CCISCO) organized a demonstration that drew 200 residents. CCISCO has already won passage of a code enforcement program and continues to pressure the city to include more new affordable housing construction in its final housing element.

Technical knowledge of the laws has also proved indispensable when organizing around a government mandate. State reviewers insisted that Concord make many of the changes to its housing element that CCISCO wanted before they would certify it. But CCISCO’s comment letter probably would have been ignored by reviewers if it hadn’t cited the relevant section of California housing element law at every step.

When it comes to motivating local governments, the campaign has learned that a bark is almost as good as a bite. The housing element law lacks strong sanctions for municipalities that don’t comply. But in early 2002, the Nine County Network will issue Fair Share Housing Report Cards for Bay Area cities. The grades will serve as city-to-city comparisons, so that advocates – and the cities themselves – will better understand which communities are doing their part to meet housing needs and which are passing the buck. Even before the report cards were released, the threat of increased scrutiny and unfavorable comparisons with their neighbors induced many cities to make a better effort to produce a timely and effective housing element. In addition, the Network supported a state bill introduced last year that would withhold some state aid from cities that do not develop an adequate housing element. Although the measure has not yet passed, the threat of greater enforcement made cities take the end-of-year deadline more seriously.

A bite doesn’t hurt either, though. In the absence of sanctions, public interest lawyers working with the campaign are planning legal action against cities and counties that refuse to develop an adequate housing element – or implement a good one. A Network affiliate in Santa Rosa – the Bay Area’s fifth largest city – is preparing a lawsuit against that city for not only missing the deadline for updating its housing element, but also ignoring the commitments it made in its previous housing element, such as creating 200 new shelter beds for homeless people.

Whether a municipality is welcoming or stubborn, cultivating allies is key. When a government mandate puts your issue on legislators’ agendas, allies who have other priorities – but maintain an interest in your issue – can be brought on board. Smart-growth environmentalists and faith organizations have been the campaign’s best allies. Greenbelt Alliance, a membership-based environmental organization, became a lead partner. The Alliance understood that housing elements are an opportunity to direct new housing away from open spaces and onto higher-density in-fill sites. With members throughout the Bay Area, Greenbelt brought credibility on the fast-growing edges of the region, which the housing advocates alone lacked.

Last, but not least, stay the course. When working with governments, activists can’t assume that even a very good plan will be implemented. Once the updating process is over, the struggle shifts to implementing the new commitments cities have made. Congregations Organizing for Renewal (COR) brought 400 people together to call on the city of Hayward to adopt an inclusionary ordinance. They were partially successful. “Inclusionary housing made it into Hayward’s housing element, but without a firm deadline to implement it,” says COR organizer Eva Creytz-Schulte. So the group will continue pressing until inclusionary housing is up and running. It is efforts like these, city by city, that will solve the Bay Area’s housing crisis.

Comments