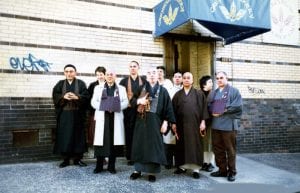

Greyston Bakery, 1987. Photo by flickr user Stephanie Young Merzel, CC-BY-2.0

The Greyston Foundation blends personal transformation, entrepreneurship, and Zen Buddhist philosophy. Can this combination fulfill the Foundation’s aim to transform both the individuals and community of Southwest Yonkers?

When he first went to work at the Greyston Bakery in Southwest Yonkers, Gary Nash worried that he wouldn’t make it. He had worked sporadically for years, battled a substance abuse problem, and finally wound up in a homeless shelter. But he was tired of living that way.

At the shelter, Nash said, he and some guys had seen an advertisement for jobs at the bakery that read: “No Experience Necessary.” Figuring he had nothing to lose, Nash went to apply.

Five years later, Nash is a production supervisor at the bakery, where he also enjoys giving tours. Besides responsibility and discipline, his job requires a knack for interacting with both co-workers and outside visitors. When his work at the bakery is done, Nash works at another job as a single father. He’s also assumed that position since leaving the shelter five years ago.

The change in Nash’s life didn’t happen magically. He said it was a slow move up the ladder. But having kicked a drug habit, all he wanted to do was keep himself occupied with work. Nash’s own commitment to change his life was aided by the Greyston bakery and its parent, the Greyston Foundation, which encourages personal transformation as an integral part of its formula for community transformation.

The Greyston Foundation‘s work coincides with the comprehensive community-building strategies being embraced by funders and CDCs around the country. But what is different about the Greyston Foundation is that its work is grounded in Zen Buddhism. Greyston is guided by the belief – shared by CDCs to varying degrees – that everything is inter-connected, and society cannot afford to ignore its rejected parts, including the post-industrial urban landscape of abandoned steel and concrete that has stigmatized southwest Yonkers.

From Riverdale to Southwest Yonkers

The Greyston Bakery and Foundation were started by the Zen Community of New York (ZCNY), founded in 1979 by Bernard Glassman, an ex-aerospace engineer who left that career to become a full-time Zen Buddhist priest. When it started the bakery in a burnt-out lasagna factory in Southwest Yonkers in 1982, ZCNY’s headquarters was the Greyston Mansion in the wealthy Riverdale section of the Bronx. At first, the bakery was the Zen Community’s livelihood and donated food to area soup kitchens and homeless shelters. In 1987, according to the foundation, Glassman decided to pursue a more activist course in Southwest Yonkers, which had the highest per-capita rate of homelessness in the country while being located in Westchester County, home to some of the nation’s most affluent suburbs. The ZCNY sold the Riverdale mansion and moved its headquarters to an old convent, the Monastery of the Blessed Sacrament, in Southwest Yonkers. Glassman also moved into the community, where he and his wife, Sandra Holmes, also a Zen Buddhist priest, now oversee the foundation.

As ZCNY’s involvement in social action grew, the bakery expanded its production. Hiring mostly local laborers – many of whom were homeless, unskilled, or otherwise troubled – the bakery managed to carve out a niche, supplying gourmet pastry to upscale food establishments in Manhattan and elsewhere. For several years the bakery was unprofitable, until Jef Hoebrichts, a business adviser, was brought on board to improve its efficiency. The bakery has now grown into a multimillion dollar operation with about 42 employees. The bakery also trains a few employees at a time as cake and tart chefs, a trade they can apply elsewhere.

The deal Greyston signed in the late 1980s to make brownies for Ben & Jerry’s Chocolate Fudge Brownie ice cream and frozen yogurt has been a major factor in the bakery’s growth. Recently, the bakery began operating 24 hours a day, with two brownie shifts and one pastry shift.

The Greyston Foundation Network

The bakery is part of the Greyston “Mandala” (meaning circle of life), or network of for-profit and nonprofit organizations. The Greyston Corporation is overseen by Hoebrichts and functions as the holding company for Greyston’s for-profit enterprises. Besides the bakery, Greyston is launching a business called Pansula, which is a Japanese term for the robes that Zen monks make from used cloth. Pansula has begun to employ local single mothers as seamstresses who make clothes, quilts, and bags from donated cloth.

“What we’re trying to do is create a community development model that integrates the for-profit, not-for-profit, and spiritual sectors,” Glassman said.

Greyston uses for-profit enterprise to strengthen communities, building on the labor and untapped potential of individuals. Glassman said the businesses should always keep in mind the transformation of people. “The product line includes the people,” he said.

Conversely, Glassman said, the foundation’s nonprofits should also be well run and efficient. Greyston Foundation raises funds (both government and foundation) for the network’s nonprofit activities, including the Greyston Family Inn (GFI), an apartment complex for the formerly homeless; and a planned facility for the care of people with AIDS.

GFI consists of 28 affordable housing units located in two once abandoned buildings on Warburton Avenue in Yonkers. Greyston received $5.8 million from New York State’s Homeless Housing Assistance program to rehabilitate the buildings. By 1996, Greyston expects to finish renovating 22 more housing units on the same street.

Plans are moving forward for Greyston’s AIDS project, which involves the purchase and renovation of the monastery in which ZCNY currently rents space. The building is to contain 34 housing units and an adult day care health center for Westchester County residents infected with HIV/AIDS. Other offshoots of the Greyston Network include:

- Greyston Builders was the principal subcontractor for the renovation of GFI. Greyston Builders employs minorities to renovate affordable housing while becoming trained in construction work;

- Greyston’s daycare center, located among the inn’s residential units, currently providing care for 53 children. The center is open to GFI tenants and neighborhood residents;

- Community outreach efforts, such as two community gardens and a planned cafe/community center. Glassman and ZCNY are also active in interfaith groups within and outside of the community, such as the Westchester Interfaith Housing Network and the AIDS National Interfaith Network.

The AIDS facility, the bakery, Pansula, along with all Greyston’s other projects, are stitched together with threads of Zen Buddhist belief. One of those threads is the importance of trying to “become” the given situation and look at it through those eyes. “If not,” Glassman said, “you’ll be looking at it as an outsider.” Glassman said he frequently sees well-meaning organizations set up projects that don’t take into account people’s situation at that point in time. For example, he noted, after the big earthquake in Mexico a few years ago, one company organized a project to build a community facility with modern plumbing in a Mexican village. The village had operated around a central well, where the socializing, contacts, and business transactions among residents took place. The new facility disrupted the social structure of the village, Glassman said, by failing to take into account how it had operated.

For Greyston, starting from a realistic point with workers who were chronically unemployed or homeless meant acknowledging that many were initially unskilled, and making sure not to put people on a complicated production line.

Another Zen principle incorporated into the foundation’s work is the importance of including everyone and everything in the transformation effort. Glassman said his group tries not to look at the government, the rich, the Republicans, the Democrats, etc., as the enemy, but rather, to work with all members of society.

The Greyston Foundation’s work holds some similarities to asset-based community development, which focuses on tapping into the resources that exist within communities – even disinvested ones. Glassman said it’s important to work with ingredients available within the neighborhood. For example, some members of the Zen Community started out looking at how daunting the task of providing an AIDS care facility was when they had no money. But, wanting to place the care facility in Southwest Yonkers, which has the highest population of people with AIDS in Westchester County, the group decided that an appropriate starting point would be to use the ingredient right underneath them – the convent where ZCNY and Greyston are located.

Changing the Consciousness of Individuals

Perhaps most significantly, Zen tradition guides Greyston’s emphasis on personal empowerment and transformation. Employees and residents of GFI are encouraged to develop their sense of responsibility for themselves, their families, and their co-workers. Greyston does this in several ways.

Greyston provides a supportive environment for workers. Along with on-the-job training, the bakery holds motivational training sessions a few times a year, during which employees take the whole day to work in groups on their motivation, social skills, and self-esteem. On a daily basis, Greyston tries to cultivate the sense of being part of a larger effort by organizing its employees into teams. On top of their regular salaries, crew members can earn production bonuses based on group effort. Glassman said the bonuses enhance not only productivity, but crew members’ sense of responsibility for the overall effort. Getting people to begin to see that interplay is a major step in changing the consciousness of individuals, he said.

The crews also make collective decisions on work policies and procedures. According to Scott Perkins of the Greyston Foundation, the Zen community has “pretty much turned the keys over to the employees.” Gary Nash noted that when two crew members recently wanted the same day off, the staff decided by voting on the matter. Management’s increased effort to foster a worker-friendly environment has helped dramatically reduce employee turnover, according to Nash. He estimates that turnover was once around 50 or 60 percent in a given year, but is now about 15 percent. However, he attributes part of the decrease to more selective hiring practices.

GFI encourages the transformation of its tenants through access to an array of various support services, some in-house and some in connection with other community agencies. But residents are asked to demonstrate their initiative before moving in, by taking buses to attend outreach sessions. Judy Shepard, GFI’s executive director, said that all of the 20 people who attended a six-week outreach program with Greyston this year completed the program. Of those 20, Greyston was able to house 15 tenants, and the rest found housing elsewhere.

The outreach sessions concentrate on life skills training and bolstering residents’ self-esteem and sense of personal responsibility. “By the time they move in, they know we believe in them, so they tend to believe in themselves,” Shepard said.

Life skills training, provided in-house through a grant from the Better Homes Foundation, is ongoing for tenants after they move in. Tenants also participate in parenting classes, one-on-one counseling, substance abuse treatment, if necessary, and job training and career counseling. Some residents find work with the daycare center, which employs about 15 people, while some are hired for other positions within the Greyston Network. All are encouraged by Greyston to continue their personal development to the point of self-sufficiency.

GFI’s record shows that, of the 91 people now living there, 44 of whom are adults: 17 are employed, two are enrolled in GED programs, and four are enrolled in college programs. Overall, since GFI opened its first building in 1991, 35 tenants have completed Greyston-sponsored job training, 10 have graduated from GED programs, three have graduated from college programs, and eight have moved into apartments in other areas of Yonkers.

Glassman said his group’s efforts are too young to determine whether they have actually begun to transform the neighborhood. He’s encouraged by the signs he sees in the changes in people’s lives, and he sees these small steps as essential building blocks of community renewal.

Right now, Greyston’s energy is focused on giving people like Gary Nash the chance to change their lives. Once people get food back onto their plates and return to a functional life (evidenced by such seemingly mundane activities as paying bills), then they can take the next step. The next step, according to Glassman, is for people to become involved in the political environment of the community. One way Greyston tries to encourage this is through its tenants organization, which focuses on tenants rights, the management and maintenance of GFI, and financial responsibility meant to lead to eventual equity ownership of the building.

Whether Greyston’s various projects hold lessons that can be replicated elsewhere remains to be seen. Glassman said his organization has had many requests to help outside groups develop programs. Although the foundation itself doesn’t yet have the capacity or energy to move its efforts beyond Yonkers, Glassman said, “If it does hold and work in other areas, I think the model will be valuable.”

RELATED ARTICLE: An update on Greyston Bakery, 2021

Comments