When the second elevator in Jenny Lind Hall stopped working in early 2024, Elvester Kennedy thought he could wait it out. The first elevator had broken down years before and disabled residents relied on the remaining elevator to access the outside. Kennedy’s sister urged him to get out of his fifth floor apartment because he uses a motorized wheelchair.

“I kept thinking, if a fire broke out or something happened, I’d be in trouble,” Kennedy says.

When Kennedy accepted management’s offer to relocate to an extended-stay hotel in a different part of town, emergency crews carried him down the stairs. It was his first time outside in five weeks.

Jenny Lind Hall in Springfield, Missouri, provides affordable housing to elderly and disabled residents through support from the Department of Housing and Urban Development. But broken elevators are not the first problem tenants have lived with. Even before the building lost elevator access, Kennedy says, he and his neighbors dealt with problems like mold, bedbugs and leaking windows.

These conditions are familiar to tenants of Millennia Housing Management, the company that owns Jenny Lind Hall and about 280 other apartment buildings across 26 states. Tenants in the nationwide Millennia Resistance Campaign have for years reported deadly conditions in the company’s buildings that have led to multiple deaths. Last year, HUD banned Millennia from entering new federal contracts and the company announced plans to sell off swaths of its portfolio. Since then, activists have called for HUD to perform due diligence on prospective buyers.

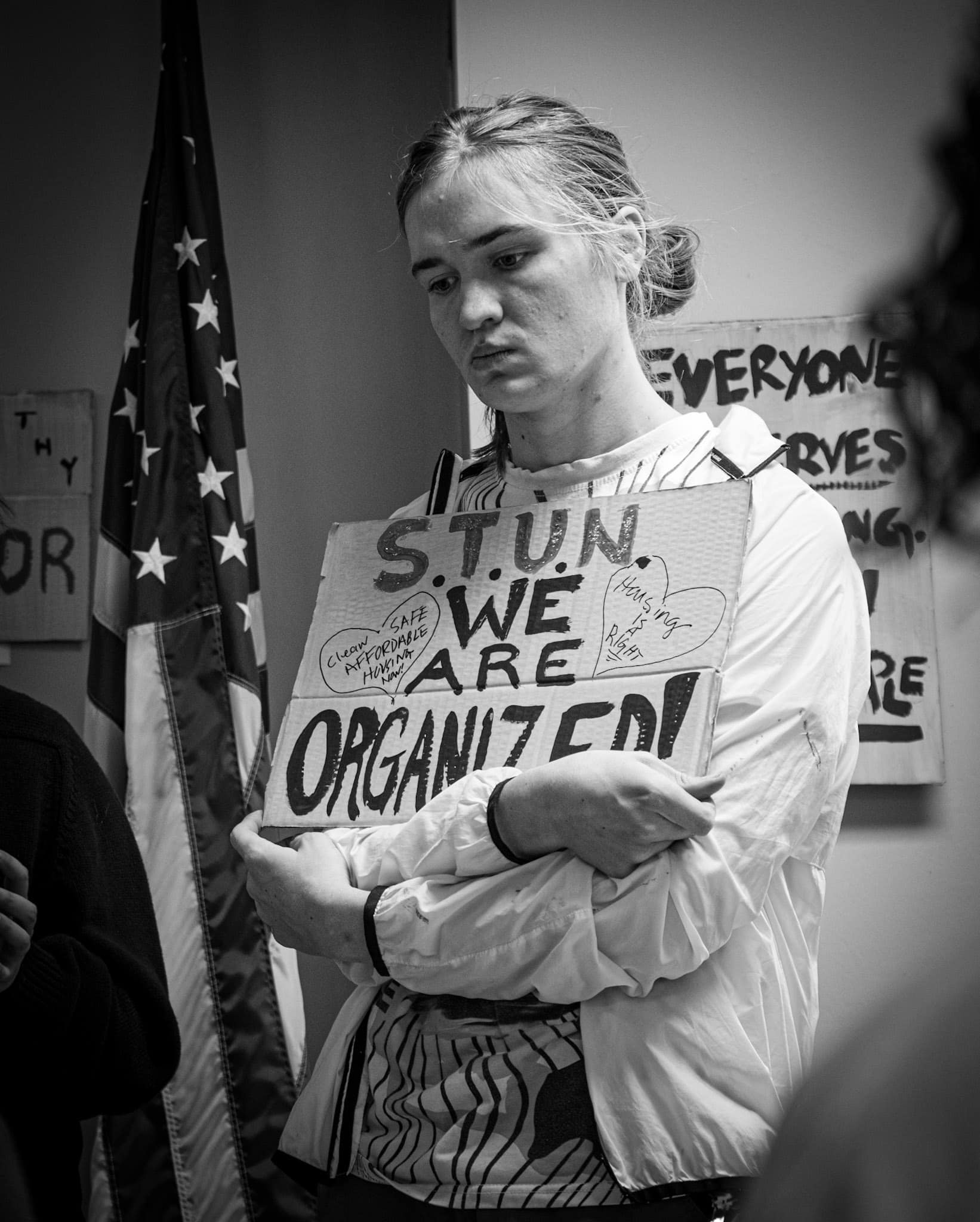

Jenny Lind tenants who are working with Springfield Tenants Unite, a citywide tenants union that organizes a network of tenant unions at individual properties, say they have seen no sign of Jenny Lind Hall selling any time soon. They’re calling for the city to replace the elevators and to put Jenny Lind Hall in receivership to take control from Millennia.

Days after STUN held a Jan. 25 housing justice rally at Jenny Lind Hall, the City of Springfield gave Millennia a 60-day notice of its intent to place the building in receivership. STUN organizers hoped this would start the process of taking control of the building away from Millennia.

But those 60 days have come and gone without the City of Springfield filing a petition for receivership. When Shelterforce/Next City communicated over email with the city’s director of building development services, Martin Gugel, he did not confirm any plans to move forward with the process, saying the city is monitoring the situation and that “positive and reasonable movement is being made by [Millennia] on the elevators.”

Gugel told a local columnist that new elevator parts had been ordered and “should arrive in July.” In emails obtained by Shelterforce/Next City, Frank Sinito Jr., Millennia’s vice president of operations, told city officials that the elevator parts would ship in late July and “the modernization should take roughly 6-7 weeks from start to finish.”

STUN has long been critical of the city’s lack of action to fix conditions in the building. Kennedy described his talks with city officials as “lip service.”

In a statement to Shelterforce/Next City, a Millennia spokesperson said a contractor has started “a full elevator modernization, with inspections, measurements, and surveys conducted in February and March.” The Millennia spokesperson added that management has offered hotel stays to tenants affected by the outage and that “the most recent bed bug report was resolved quickly.”

The union has taken issue with the city for not including tenants in talks with Millennia. Beyond Jenny Lind, STUN is using the building as a case study to push for rental licensing and proactive building inspections across the city.

STUN origins

When Springfield Tenants Unite formed in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, STUN co-founder Vee Sanchez was a single parent who had lost her job as a cook in a local restaurant. “Of course, getting laid off did not mean rent was not due,” she says.

Sanchez had worked hard to find housing security and saw it washed away by factors outside her control, so she talked with other Springfield renters going through the same thing.

“We did not want to sit and be made homeless quietly,” Sanchez says. “It was people who were impacted — working class people, moms, people with families — coming together, talking about what was going on and … what we can do to stand with each other.”

The group started showing up to city council meetings and giving input on how federal pandemic relief funds should be used. STUN’s first “ragtag” campaign succeeded in getting a portion of the city’s relief funds dedicated to rental assistance.

In that early campaign, Sanchez and her fellow organizers got a taste of collective power. “We also got really clear that we were struggling before COVID and we were going to continue struggling after COVID… until there were deeper, more systemic reforms that could actually support working people,” she says.

Having connected with the Kansas City Tenants Union through her previous work with Missouri Jobs With Justice, Sanchez had seen that people were organizing around housing—and seeing results — in Missouri.

“I saw the crazy amazing work that they were doing” with rent strikes and other organizing tactics, Sanchez says of KC Tenants. “There was a clear example of what that could look like at the local level. And I saw that we didn’t have that here. I wanted to do something about that.”

As part of the Coalition to Protect MO Tenants, a statewide tenant organization, Sanchez trained with KC Tenants on how to run a strategic campaign.

As members built relationships, took on leadership roles and learned the tools of organizing as part of the statewide coalition, Sanchez said the conditions were right to build a local tenants union. STUN’s community agreement states that “those closest to the problems are closest to the solutions,” and tenant involvement is central to its theory of change.

Organizing in Jenny Lind

Jenny Lind tenants and STUN organizers say one of the two elevators has been broken for years. The second went in and out of service for months before it stopped working entirely in early 2024. That’s when residents went to local news media and connected with STUN through Kennedy’s caretaker.

In the year since, tenants have remained vocal about the elevator and other health and safety problems at the property, telling reporters they feel like “hostages.” Residents say they have rationed groceries and missed doctors’ appointments and family gatherings because they couldn’t get downstairs.

“Fix the elevators as soon as possible, because people are gonna die if they don’t,” Kennedy says.

While some tenants have brought public attention to the situation, STUN organizer Jai Byrd and Kennedy say many are afraid to speak up and organize. It’s also hard to organize with your neighbors when a building isn’t accessible enough for you to leave your floor, Byrd says.

Despite the building’s designation for tenants over 62 and people with disabilities, it lacks necessary accessibility features like wheelchair-accessible doorways or wheelchair clearance in bathrooms. Resident A. Jackelyn Moreau says the sidewalks and ramp entrance of the building are crumbling.

Kennedy says residents who have aides to help them with day-to-day tasks have an easier time living in the building than those who don’t. His aide, for example, took his bedroom door off the hinges so his chair could get through.

STUN has organized a weekend program of volunteers to get groceries and laundry up and down the stairs for tenants while they wait for the elevators to be replaced or the city to file for receivership. Gugel and Millennia both said the company has also delivered groceries to tenants.

Last year, the city of Springfield declared Jenny Lind a nuisance property and found Millennia non-compliant with city code. Now, Gugel says, the city’s department of Building Development Services has been speaking with Millennia every other week and the company has “been keeping [the city] updated as they move forward with replacing the elevators and addressing any other issues that have come up.”

Before Gugel’s statement to Shelterforce/Next City, Sanchez said she believed Millennia would comply with the city enough to avoid receivership, but she was skeptical of promised results.

“The tenants got tired of hearing this story. For years, they have been strung along,” Sanchez says. “Millennia is well versed on how to do the very, very, very, very bare minimum to evade accountability.”

Tenants provided Shelterforce/Next City with documents dating back to May 2024 showing that Millennia has been providing conflicting information and timelines in its updates on elevator repairs.

STUN argues that Millennia’s communication with the city doesn’t cut it and tenants need to be kept directly up to date about the repair process.

STUN organizers said they have worked with the national Millennia Resistance Campaign in the past, but they’ve had a local focus since the prospect of Millennia selling Jenny Lind looked slim. Sanchez thinks the only way of getting these buildings out of Millennia’s control may be to “make it more costly for them” to keep them.

Since the January rally, STUN has called for the city to replace the elevators and bill Millennia, hold Millennia accountable for code violations, and place the building in receivership, managed by “a reputable organization.”

Eventually, Sanchez says, STUN and Jenny Lind tenants want the building to go to a local buyer “that we can see face to face, that the tenants can talk to across the table like human beings and not just dollar signs.”

National problems on a local scale

As the Millennia Resistance Campaign urges HUD to improve oversight and code enforcement in subsidized housing nationally, STUN is lobbying for a rental licensing and inspection program in Springfield.

The union intends to use attention on Jenny Lind Hall to apply pressure for its call for a “Healthy Homes Guarantee” policy. Currently, the city only inspects rental units when tenants make complaints.

A pilot program for rental licensing and inspections has been in the works with Building Development Services and city council’s Community Involvement Committee, but STUN recently called out the city for canceling the committee’s meetings and leaving the policy in “limbo.”

STUN argues that a system for regular rental inspections and code enforcement would make the city more proactive in enforcing safety standards for housing. Organizers say that the current system is confusing and that tenants fear retaliation for making complaints.

STUN organizer Daniel Behlmann told the Springfield News-Leader that the housing in worst condition is often “the last alternative to homelessness,” and its neglect speaks to how the city’s poorest residents are left behind. In the case of tenants in subsidized housing, Sanchez and Byrd argue that they should be the city’s most protected tenants.

Even with inspection programs, poor conditions can still slip through the cracks. In Columbus, Ohio, Millennia qualified as one of the city’s “most code violating landlords” according to local media. In 2023, an Atlanta judge fined Millennia for code violations in a condemned apartment complex.

Jenny Lind Hall’s website still lists elevators as an amenity and new tenants continue to move in.

“People need a place to live,” Kennedy says. “This place is the Taj Mahal compared to some of the places they’ve lived in.”

This story was published through a collaboration between Shelterforce and Next City. Next City is a nonprofit news outlet that publishes solutions to the problems that oppress people in cities, inspiring social, economic, and environmental change through journalism and events around the world.

Comments