Susanne Schindler is a trained architect and historian and a research fellow at Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies. In 2024, Schindler co-authored Cooperative Conditions, a book about Zurich’s long-standing model of non-means tested limited-equity cooperatives. Samuel Stein is a housing policy analyst and a trained planner and geographer. In 2019, Stein published the book Capital City about the power of real estate over American urban planning and housing politics.

The two authors collaborated on a book launch for Cooperative Conditions, hosted by Julie Torres Moskovitz, during which they discussed the differences between cooperative housing in Zurich and the new social housing movement in New York City. Afterwards, Schindler and Stein decided to hold a longer, written discussion about the merits of different rent setting models.

Schindler: Why does the U.S. have such a hard time imagining an alternative to either pegging rent to income, as is the case for those who qualify for “affordable housing,” or equating rent with whatever someone is willing and able to pay, so-called market rate? Why is it so hard to set rents in relation to what I would call the real cost of financing, developing, and operating housing?

I fantasize that if we could agree on what constitutes a fair price for housing, that would apply to all housing. We could stop trying to value-capture ever-rising market prices to pay for below-market rate homes—possible only where those market prices are already very high, and an impossible game of catch-up. Instead, we could take a long-term view of housing prices, aiming to keep monthly charges low, but high enough to make sure buildings are maintained and will serve several generations.

Rent stabilization comes closest to this idea, but it’s so contested that few municipalities allow it, and many states ban it outright, although the idea is certainly making a comeback.

But trying to describe the real cost of housing is not just important for rental homes. The new Florida condominium laws were written to do just that in order to avoid more disasters like the 2021 collapse of the Champlain Towers South condo in Miami (which was due, in part, to deferred maintenance and capital improvements).

So, what do you think? How could we—as a society—design fair rent?

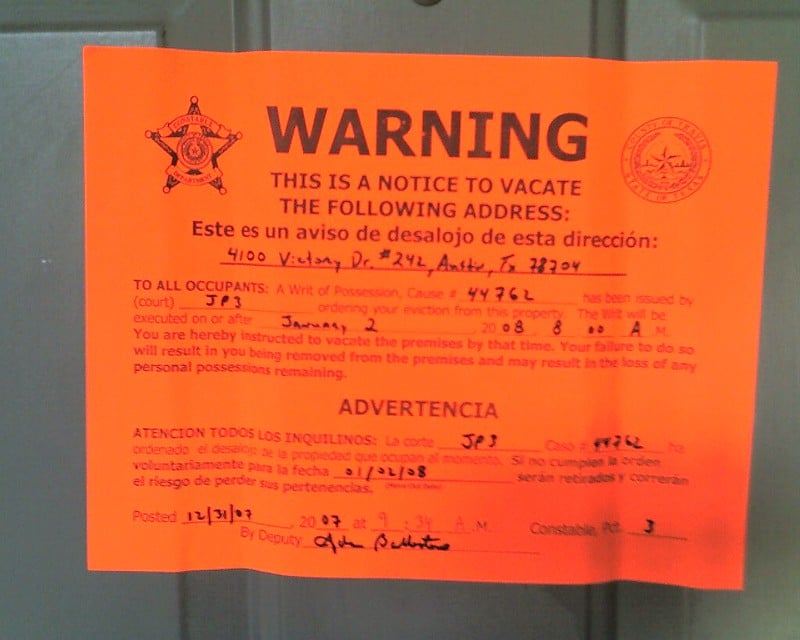

Stein: Let’s take a step back: What is rent? For economists, it’s the “unearned increment” above the actual cost of goods and services, charged by an owner because they have inordinate market power. For tenants it’s the amount of money demanded each month to remain in their homes, and for landlords it’s the maximum amount of money they can charge, set either by local laws like rent stabilization, individual regulatory agreements with the government, or market conditions—and often a combination of all three.

What constitutes a fair rent? For economists, “rent” is unfair and undesirable. It’s not just the money residents pay each month, but specifically the portion of that fee which owners can charge solely because they have class monopoly control over an artificially scarce good. For tenants, “fair rent” generally means what’s affordable within their budgets, or perhaps what the owner really needs to maintain the building. For landlords, “fair” might mean as much as they need to run the building plus as much as someone will pay for the space and location, or it may refer to “fair market rents,” a calculation made by HUD based on the amount nearby landlords are charging for similarly sized units.

Understood this way, rent doesn’t just mean one thing at any given time. Different, conflicting models sit side by side on the same city blocks, and different actors disagree on whether or not any of them are “fair.” So, having stripped back these components, how do you think we should be thinking about setting “the rents” in a new development? How is it done in the places you’ve studied?

Schindler: You get at the political as well as very practical problem at the heart of this issue, namely the gap between what someone can afford to pay for their housing and what it costs to finance, develop, and operate a building. A homeowner pays for the mortgage, taxes, insurance, and upkeep. A renter pays for precisely those things in the form of rent to the owner. In addition, the renter often also pays for the owner to make a profit.

When it comes to filling the gap between household income and housing price, we commonly talk about subsidies. Subsidies (in the form of a Section 8 housing voucher, for example) are typically pegged to HUD’s fair market prices. But what is a fair market price when market prices in a geographically limited sector like housing are rarely self-correcting or natural, as recent price-fixing schemes have shown? Why can’t we think about keeping housing costs and prices down rather than subsidizing a housing market that has no incentives to do so?

But what you asked me to talk about is how some other places have addressed this issue. Here is one example. For over a century, Zurich, Switzerland, has adhered to the notion of “cost rent” (Kostenmiete). The idea is to establish the maximum rent that can be charged for residential real estate in the hope that it is “fair.”

When applied to nonprofit housing, for instance cooperative housing (which is considered rental housing in Switzerland), the idea is to establish rent that neither requires subsidies nor generates a profit. This housing sector is under close governmental oversight. The formula applies to all housing, though, at least in theory. In the case of for-profit housing, however, it is left up to tenants to challenge unfair rent increases, which is, of course, much harder to do.

How does it work? The cost-rent formula takes into consideration capital and operational costs of a particular property. Capital costs include everything that has been invested into the building, from land acquisition to construction cost to debt service. These are multiplied by the country’s benchmark interest rate. Operational costs (operation, maintenance, and capital reserves) are defined by the building insurance value, or what it would cost to replace the building in case of total loss, reassessed every few years by an independent entity. This is multiplied by an operational quota set by the city of Zurich. The formula results in the total rent that may be charged for the property.

All of this means that cost rents can go down when interest rates fall; they can also go up when they rise or when major investments are made to a building. It also means that cost rent for new buildings tends to be high since cost rent is calculated per building, not across portfolios. In the case of cooperative housing, however, rents tend to go down over time because land is not resold and land value stays constant. The same rationale—freezing land values—underpins community land trusts in the U.S.

Whatever its practical limitations, the cost rent formula attempts to define what constitutes fair rent across all rental housing. And it recognizes housing as a capital-intensive asset not only in the moment of its creation, but over its existence.

Stein: The Zurich model helpfully scrambles our expectations about what is fair and what is affordable. As we’ve alluded to earlier, in the U.S., “affordable housing” almost always means housing where the cost to the resident is pegged to a percentage of their income, often with an additional ongoing subsidy to cover the difference between what the tenant can afford to pay and what the owner seeks to charge. Owners are seeking to cover the costs of taxes, debt service, labor, and materials, but they are also pursuing profit—particularly when the landlord is a private operator rather than a public or not-for-profit entity. And using low-income housing tax credits and Section 8 vouchers, most “affordable housing” in the U.S. is in fact for-profit housing.

When monthly charges are simply pegged to operating and capital costs, as they are in Zurich’s cooperatives, and buildings cannot be sold, the profit motive is obliterated and housing is functionally decommodified. But it is still not necessarily affordable to people who need housing. In a city like New York, that doesn’t just apply to a marginal population, it’s the majority. As of 2023, the median renter household in New York City earned just $70,000, according to the Housing and Vacancy Survey. Meanwhile, the median asking rent for a vacant two-bedroom apartment was $3750 in January 2023—a rent that would command the majority of the typical household’s income every month. New York City housing data doesn’t make it easy to figure out how much of that asking rent is costs and how much of it is profits, but it seems likely the cost rent would be out of the “affordable” range for a great many—if not most—families. So while a cost-rent model might appeal to a lot of Americans’ sense of justice, it still wouldn’t address the problem that incomes are too low and housing costs are too high.

Schindler: What if housing were provided as a public service, just like education or roads? We never talk about public schools being “subsidized”; an education is something we (as a society) have decided is required to keep a democracy and an economy functioning. Everyone can attend a school.

That doesn’t mean schools come for free. The cost to operate them, however, is covered by general tax revenue, not individual payments billed to you according to your use. Yes, what you pay into that tax bucket is calculated on the basis of your income. But those payments go into a general fund, albeit tied to your local school system. It could be the same for housing.

This kind of all-encompassing, overarching housing system is probably what countries that have eliminated private property and tried to socialize housing entirely have tried to create. Trying to run such a centralized system is probably a nightmare. But that’s not a reason to not think about it: a system based on private property rights doesn’t seem to be working either.

It is worth noting that the question of how to design fair rent was a relevant one even in the planned economy of the Soviet Union, as Gregory D. Andrusz describes in his book, Housing and Urban Development in the USSR (see page 28). Tenants paid monthly fees which covered only a fraction of the operations, not capital costs, and those were adjusted slightly depending on the condition of the apartment, its location, and household income.

So I’m going to throw a different question back at you. I’d like to move away from rental housing and talk about the design of prices in homeownership models, specifically limited-equity co-ops. You’re a resident of one. Could you reflect on the tension between income and wealth restrictions in the access to such housing? How do those restrictions (or lack of them) relate to the share price a new resident pays for a home, and how do you all, as voting members of the cooperative, decide what to pay on a monthly basis for capital and operational costs?

Stein: The personal is political, as they say, so here’s how it works in my limited-equity cooperative—which is far from perfect, but is perhaps demonstrative. For the last four years, I’ve lived in a Housing Development Fund Corporation, or HDFC, a shared ownership program in New York City. In 1979, the landlord of my building and seven other private rental tenements alongside it fell behind on his property taxes and abandoned the buildings. The city of New York took possession, got money from the HUD Section 510 program, hired residents and contractors to modestly renovate the apartments, and then sold shares in them back to the tenants at a low cost under three conditions: anyone who couldn’t buy would remain a rent-stabilized tenant (though all bought in); when the shareholders sold their apartments, they would have to sell to households making less than a certain income threshold (90 percent of AMI); and half of the difference between what they bought and sold for would go back to the co-op’s reserve fund as a “flip tax.” There is no sales price cap, but the board has to approve offers and they try to ensure they are reasonable. When I bought my share, it cost roughly half of what a market-rate apartment would have fetched. Meanwhile, we pay a very low monthly maintenance fee. I’m sure it’s lower than the co-op’s operating costs, but we cross-subsidize with retail rents—11 storefronts across the 8 buildings, all rented to businesses we all need (like a laundromat and a barbershop)—as well as periodic flip tax revenue.

Schindler: But are the terms that the city and HUD designed back in the 1970s fair? The terms required an income limit, but not a price restriction when an apartment goes up for sale. That means that a potential buyer’s income may be low, but that buyer may need to have wealth to afford a downpayment. The overall co-op benefits by taking a portion of that added value, allowing you to keep your carrying charges low, just as the retail rents offset what you would otherwise have to put in a capital improvement fund.

Zurich co-ops are founded on an inversion of that approach: there is no income restriction, and when you leave an apartment, you get your share value back at the same price point you bought in, no appreciation paid out. Why don’t we have that in the U.S.? Why isn’t there housing that is open to all, regardless of income; where monthly payments are pegged to the real cost of financing, developing, and operating the housing, ensuring the building is maintained and periodically upgraded; the resident’s private financial gain is low monthly charges; the public’s gain is keeping that housing accessible and affordable for future generations. What would it take to at least offer this model as one of many?

Stein: We do have a program somewhat like that in New York: the Mitchell-Lama cooperative program. There, resale prices are strictly capped and prices have remained far lower than in HDFCs (typically well under $100,000), and a small fraction of market prices. Monthly charges are just expected to cover the maintenance, and they usually do—though in some cases they have lagged.

The main difference between that and the Zurich model, however, is that under Mitchell-Lama, potential coop members’ incomes are restricted at the time of purchase. These apartments are not “open to all” because the rules demand that they go to people with low and moderate incomes. The Zurich model promises to be “open to all,” and in a sense it is. I think a lot of Americans would love the idea of not having to means test to get into decommodified housing. People hate income-certifying and proving they are deserving of something everyone should have. But there’s still an enduring mismatch between typical wages and cost-based rents, and as long as that gap remains, “open to all” only means “open to those who can afford it.”

Here we bump up against the limits of political economy. It’s a tremendous political accomplishment to decommodify housing, and yet when all the inputs into housing—land, labor, energy, materials, financing—remain commodified, decommodification can only reduce prices by so much. And when workers are stuck in low-paying jobs, it may not be enough. Capitalist housing reform is a slog, and it’s not just because the opposition is so fierce; it’s also because the entire system is set up to ensure that exploitation and profit are present all along the value chain.

So to come back to your initial question: could we—as a society—design fair rent? “Fairness” is a complicated matter, but we absolutely should, must, and will try. But we will keep pushing up against these limits as long as we’re decommodifying housing in a commodified world.

Comments