This article is part of the Under the Lens series

Street Blocks to Alphabet Blocks: The Housing-Education Connection

In a world where educational justice and housing justice movements too often seem separated, Akira Drake Rodriguez’s research connects them instead. Currently an assistant professor of city planning at the University of Pennsylvania’s Weitzman School of Design, Rodriguez is also the author of Diverging Space for Deviants: The Politics of Atlanta’s Public Housing, which explores resistance in that city’s public housing to widespread closures. We spoke with her about how school closures in Philadelphia affect neighborhoods, alternative visions for those schools, and how communities are starting to organize to change the way school facilities planning is done.

Miriam Axel-Lute: Thank you for joining me, Akira, to talk about school closures and equity. Tell us a little bit about yourself and how you got into studying this topic.

Akira Rodriguez: I started off researching tenant organizing and public housing in the city of Atlanta. Atlanta was the first city to have public housing, with Techwood Homes, and the first city to tear virtually all of it down. I was interested in learning about working class– and Black women–led politics in the city following the demolition of public housing. I was looking for how they were organizing and engaging in a political capacity around issues that mattered to them, particularly in their communities.

Due to the absence of public housing physical developments, and the introduction of mixed-income or HOPE VI developments, there weren’t tenant associations in those new developments—for public housing residents, at least. Black women started organizing and meeting in public schools. It was really mimicking a lot of what I saw in public housing, these shared geographies or communities that had shared issues and problems that were largely due to an absence of public goods and services in their communities.

They use the physical space of the public school to engage and make those grievances heard to the state.

I started looking at public schools as infrastructure, whether it’s physical infrastructure or social infrastructure, in Philadelphia. We had this earlier experience in Philadelphia in 2013, where about 30 schools were closed. [I looked at] what changes to the neighborhood and the community and the built environment followed after the closures, and how to incorporate those lessons into future school facility planning processes.

I love that connection that you made in Atlanta about where the organizing went and how it persisted when the availability of the housing changed. Let’s pull back a little bit and talk about how neighborhoods affect schools and schools affect their neighborhoods?

That relationship has always really existed, I think, in ways that are not lifted up in the research, in particular in housing research. We all know when we look at home prices that the quality of the neighborhood school is a driver of that. I really wanted to better understand not just how the quality of the school could impact the home prices, but what other amenities and services the public schools provide.

Similarly, of course, when the quality of the school is perceived as bad, then that translates into lower home values. This impacts the stabilization of the neighborhood; when you have low property values, not only are you generating lower property tax revenues, which reify the declining quality of the school, but also you risk depopulation and neighborhood destabilization.

A good school is an open school and a school that people want to be at. It’s much more than just test scores and grades and attendance, but also these broader services and spaces that schools serve as.

In thinking about the example in Atlanta, schools allow people to interact with the state, whether it’s through PTA or school board meetings. These are ways for people to make their voices heard in a much more responsive process than voting, for example.

Do you think that the advent, in a lot of places, of more school choice, the decoupling of necessarily going to a neighborhood school when you live in a neighborhood, has affected this relationship?

Definitely. In thinking about the role of the neighborhood school and school choice, we’re seeing something that’s comparable to the housing struggle.

I’ve written about this in the past with my colleague, Rand Quinn, about the parallel pathways of schools and housing in the country. Particularly following integration or desegregation with Brown v. Board in 1954, we’re seeing this demonization of public schools in the same way that we saw the demonization of public housing. In that demonization, you lose your political viability and popularity, and you start to see that defunding coming from federal, state, and eventually, local levels.

Then that has ripple effects on the neighborhoods and the communities?

It has ripple effects. … I spoke earlier about the role of the public school allowing you to engage with the state. When you have this privatization of public schools, still using public money, but overseen by a corporation or nonprofit, it makes it much harder to engage in broader issues around distribution and equity of public goods and services. You become a consumer or a client engaging with a service provider in a way that has what I think are substantial ripple effects on democracy and political engagement.

Consumer rather than a citizen?

For sure.

You said earlier, “A good school is an open school.” Let’s look at a neighborhood and talk about what can happen when a school closes. I know you have some examples of some different ways that it happened in Philadelphia in the 2013 closures.

Yes. The 2013 closures were initiated through a private process. It could be framed as a planning process, but there was no community engagement or even a broad awareness that this was happening. The school district of Philadelphia engaged Boston Consulting Group to write a report on school facilities in the city. This looked at very technical data, such as what we call Facilities Conditions Index or FCI, which analyzes the systems of a school—plumbing, roof, electricity, etc.—estimates the condition of them, and then estimates the cost to get it into good condition.

If the cost of the repair is higher than its replacement, usually you’re going to remove that system. If enough systems need to be removed, then that translates into the closure of the school.

Another data point that they used was this idea of utilization. Philadelphia is a very old city. We had massive school construction at the turn of the 20th century, and mid-century, as the city is growing. It reaches its peak of about 2 million residents in 1950.

We had high schools that were constructed for 2,000, 3,000 students that, by the time this planning process is happening, are serving literally 200 students. In addition to closures, a lot of the recommendations in the Boston Consulting Group report [were for] consolidation.

There were about 250 schools, and about 60 schools were [recommended] in this report for a closure or consolidation. The board, at the time, was a state-run board. The school district’s local control had been taken away by the state in 2001.

At that point, people are organizing to counteract these closures and consolidations. Some schools are saved, but are still what I consider to be vulnerable in future processes; others are closed or consolidated.

This caused some destabilization. One of the areas that was hardest hit was an area that’s on the border of one of our more affluent suburbs, the western part of our city, an area known as Overbrook, which borders Montgomery County, a very affluent county. Residents and organizers have actually done a school funding walk where they walk from Gompers Elementary in Philadelphia over to Lower Merion School. In that 1-mile walk, there is a disparity of basically 100 percent in additional funding for the suburban school student versus the one in Philadelphia.

That particular area saw a great deal of school closures and populations have continued to decline in those areas. North Philadelphia was also an area that was hard hit. Within a few years, you see the rise of school choice in these neighborhoods. A great deal of charters reappear in the wake of these closed schools.

I recall you telling me that in some of the different neighborhoods there were different effects on the housing market when their schools closed, some of them really deteriorating, some of them actually seeing some gentrification. Can you talk about the different kinds of things that might happen?

It’s funny, I’m at home right now. I live right across the street from a school that is closed. The house that I live in is my grandmother’s house that we moved into. I was actually supposed to go to this elementary school before my family moved out of Philadelphia. During 2013, this elementary, Smith Elementary, closed. The building has been converted into rental units, market rate. The playground and parking lot are about 12 single-family townhomes that average about $650,000. The house that was my grandmother’s house, [is] worth about $150,000, to give you some comparison.

There has been a lot of development in this area, which brings a lot of young couples that eventually become young families. There’s no school. This is happening further east in South Philadelphia with a school known as Southwark, which is a K-8 school.

Right across the street is a school known as Bok, which was a technical high school. It closed in 2013 and was repurposed into a bunch of different things—a maker space, a kiddie care center and gathering spot, a place that sells soccer equipment, a cafe, and at the top, a beautiful restaurant and bar.

This space has attracted a lot of families into the neighborhood. Southwark, which was never fully utilized, especially during the closures, but was not up for closure, is now overcrowded. Ironically, they lease the gym space from Bok because they don’t have room for all their activities.

In Overbrook, we see population decline and growth of school choice. In South Philly, we see a gentrification that’s happening as a result of the closure of this inefficient state good, the redevelopment of it into housing or to new uses, the attraction of a new type of resident and homeowner, and then the slow depopulation as families move away because they don’t have school options in this neighborhood.

Are there alternatives to closing underutilized schools that would preserve the public infrastructure for public good in a different way?

Sure. We had a public housing development in North Philadelphia that was demolished and redeveloped in a HOPE VI Choice Neighborhoods initiative approach. Part of that demolition included the closure of a local school. Then this school was actually purchased by the housing authority. They put a new school in. They hired teachers from the union. It’s effectively operating as a public school, drawing students from the neighborhood. Because the space was still so large, and the population was not utilizing that full space, they started leasing to other nonprofits that had connections to [the] school—after-school program for writers, different job training [programs], different public goods and services and advocacy groups. The results have been successful; they’ve been retaining teachers and students. You’re seeing above-average graduation rates and completion rates. This is how to adapt a public school and still keep it a public good.

Communities are going to change over time. We know that. It makes sense to adapt the public good in the public space to fit the community needs. That way you’re not having to lease auditorium and gymnasium space from private developers because you’ve sold your public good.

Right. That is certainly something that could be done by school districts as well without a transfer of ownership.

Certainly. We saw it during COVID. We saw public schools that were closed for educational purposes open to provide vaccines, to provide food, to provide the pandemic EBT for those who are on free and reduced lunch. They know how to bring these goods and services to communities that need them. Schools [are] in every community. They’re like a natural infrastructure.

What you’re describing sounds a lot like the community schools movement to me. Have they been active at all in Philadelphia? Is there a way to connect that in with this work?

Definitely. Our current mayor, Cherelle Parker—the first Black woman mayor of the city, also a former public school teacher and a parent of a student—has put forward this idea of year-round schools where there’s robust before- and aftercare that mimic the workday of the average parent in Philadelphia, as well as offering robust summer program in coordination with other city departments such as parks and rec.

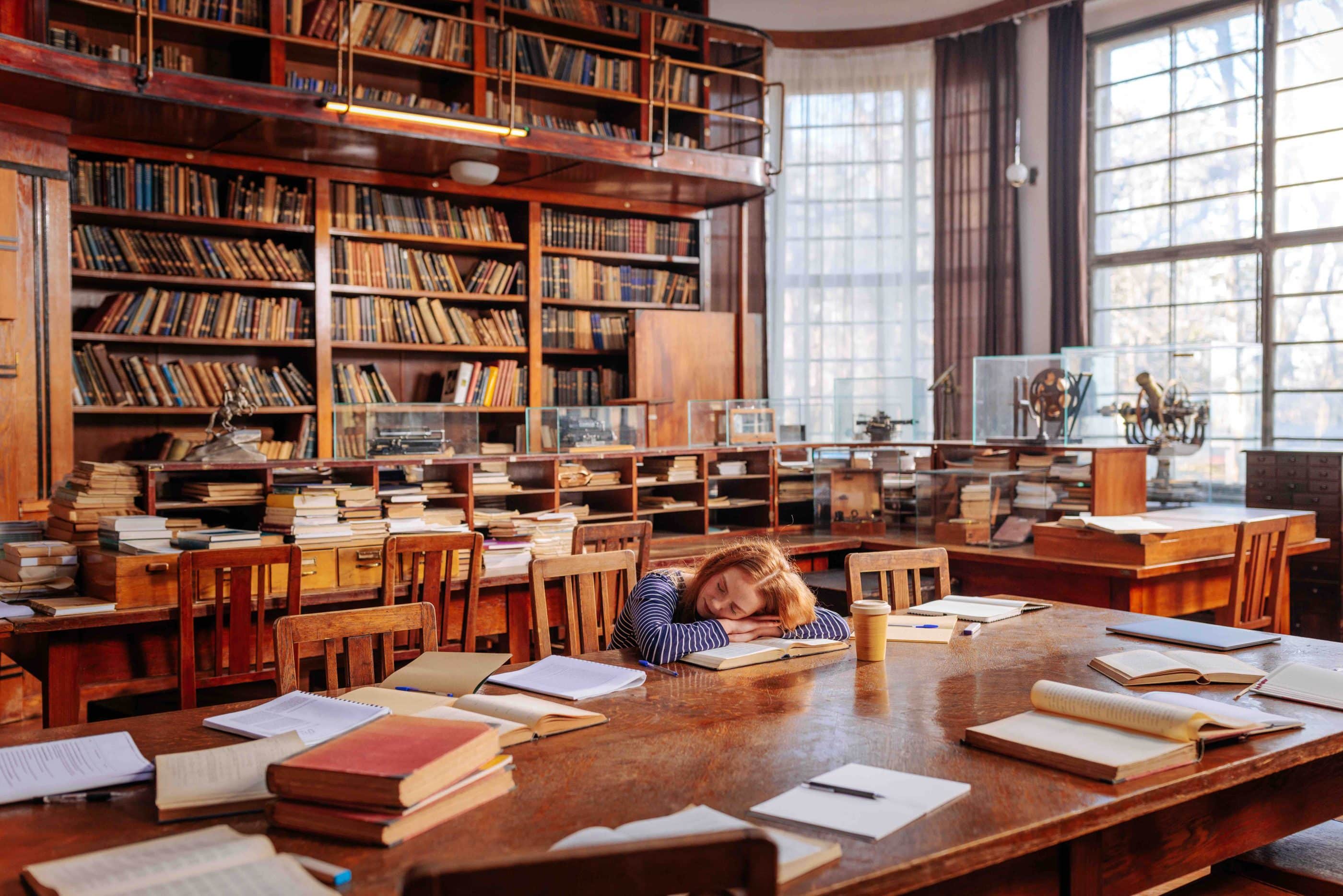

I’ve seen successful incorporation of public libraries into schools. So, again, the idea of co-locating fits right alongside this idea of the community schools movement.

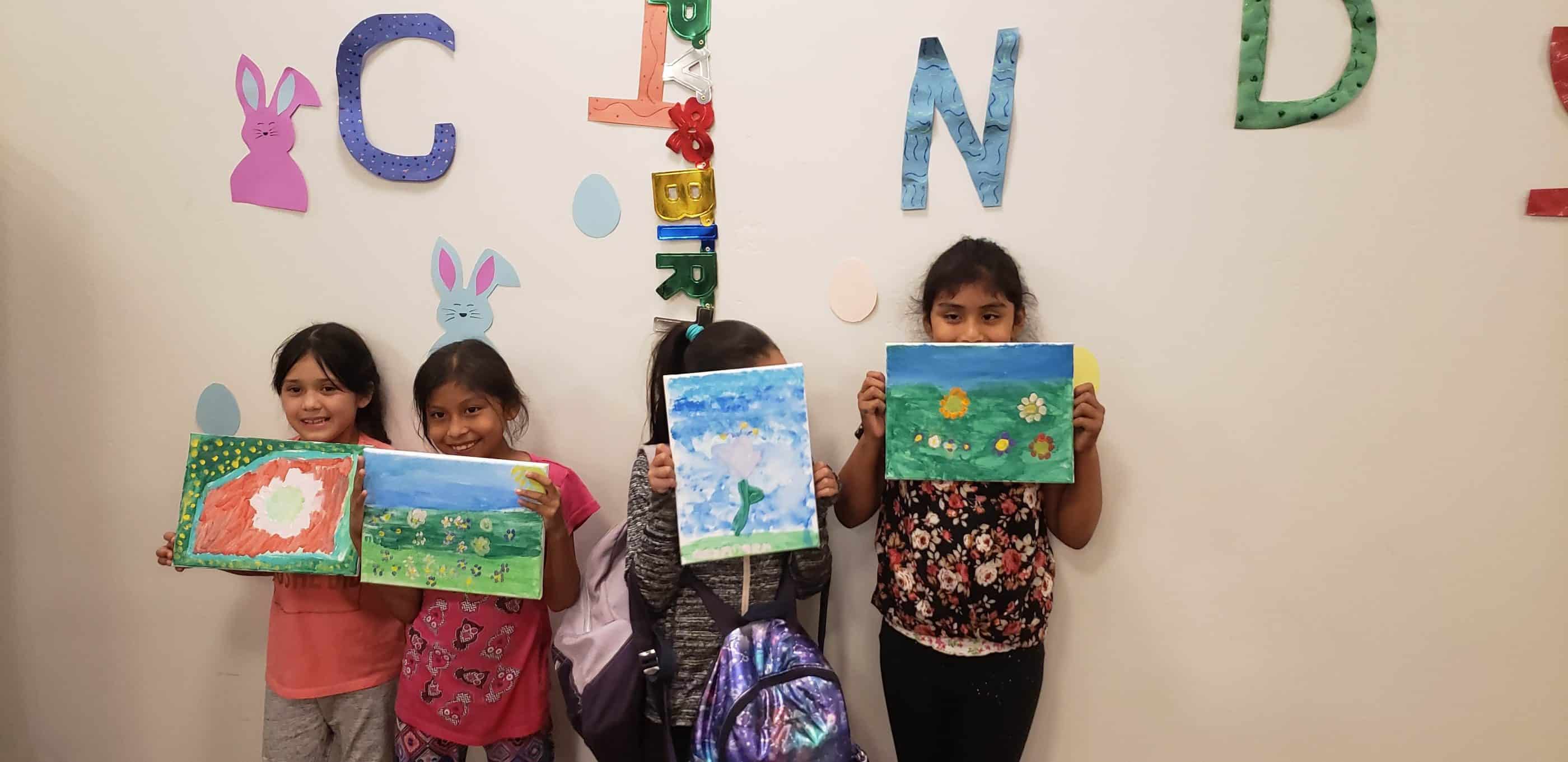

[An] earlier initiative with the previous mayor, Mayor Kenney, allocated funding to community schools to do outreach, which was especially effective in our high immigrant population neighborhoods, organizing to provide both social services, but also legal protections and care for some very vulnerable communities.

In contrast to the planning process in 2013 that led to all those school closures, Philadelphia has been working to embark on a different kind of school facilities planning process recently. Can you tell us about how that is going and how it’s different from what happened before?

Philadelphia schools were returned to local control in 2017. The school reform commission dissolved itself, and now we have a school board that is appointed by our mayor. This school board rightly understood that populations were still continuing to decline, and traditional public schools were underutilized (editor’s note: meaning having significantly fewer students enrolled than the buildings could accommodate) and also in poor condition.

The average age of a school facility in Philadelphia is about 80 years. We have many schools that were built before the 20th century that are still in operation. In addition, we have this century of ill-advised decisions around the materials that we have in our schools. We have millions of square feet of asbestos; lead in our paint and plaster and our water feeder pipes; mold; half of our schools lack air conditioning.

From a cost standpoint, [repairs and] remediation of the environmental hazards would cost about [$7–9 billion] for all 215 schools in the city. When you think about how some of these charter schools are actually housed in traditional public schools, that number could increase. The planning process that began in 2019, when it was announced, said, “You can expect some closures and you can also expect some changes in our catchment areas, which determine, based on your address, where your local school is.”

Surprisingly, in 2019, the first reaction to this announcement was not from school organizers or teachers, but from real estate developers. The one or two really good K-8 schools in the city are highly advertised and signaled in real estate ads. The idea that some catchments would be redrawn was a little frightening for the real estate industry.

With this announcement, there was also the idea that there would be a public process. The consultants from the school district would form stakeholder groups by study areas, which were geographic areas containing about six or seven K-8 schools. They would produce some recommendations that would be presented to the public, adopted by the school board, and implemented in the following year. It was a pretty traditional planning process.

The study areas were very different from each other. For instance, that Overbrook area that I mentioned, where there were very few schools, and many were in bad shape and underutilized as a result of the previous closures. An area in North Philly that also had a lot of school closures, a rise in charter school options, but also a growing immigrant population, and new schools actually being constructed. And a third area in South Philadelphia, pretty close to our downtown, where populations were growing to the point where a new middle school was under discussion.

So we have one area where school closures are pretty imminent because we have a history of declining population; one area that’s growing, but is pretty marginalized within the city; and another area that is gentrified and growing, and needs new school options.

From the start, there was a lot of suspicion, obviously because of the legacy of school closures, which had really just happened six years before. If you’re a child whose school was closed in second grade, you’re in eighth grade now and facing possibly another closure. This isn’t a long time at all. People were a little upset about how the stakeholder groups were handpicked by principals. Elected officials and community planners dominated within these stakeholder groups.

Parents, teachers, and school advocates who were left out of the stakeholder groups took a few different approaches to improving the process. First, they pushed for stakeholders to hold community and public meetings to provide what they were learning to the public before the mass public meeting.

Second, communities that were not included in the first round of study areas were beginning to hold their own meetings and discuss the alternatives so they could prepare a counter-narrative when it was their turn in the facilities planning process.

Then a third group formed, drawing in a council member and three parent and neighborhood groups, which was focused on the idea of working across these study areas, instead of fighting about closures within a constrained geography—thinking about the resources we have across the city and how we can start to reallocate them more effectively.

In all those different approaches, there was vocal advocacy and direct action. The broader sharing of information, coalition building, and advocacy in the form of testimonies and op-eds shifted the narrative toward a need for more participation. Through this disruption of the school district’s planning process, we were able to insert some more participatory opportunities, such as expanding the number of meetings, and removing the idea of closures from the list of recommendations that were provided to stakeholder groups to start with.

When you say “we,” tell me a little bit more about who was involved in organizing to push back and change this planning process.

As a result of both the state takeover of the school board in 2001 and the closures of 2013, there was actually a robust educational justice organizing infrastructure within Philadelphia. You have this citywide coalition, Our City, Our Schools, which is a bunch of different community organizations, parent groups, and student groups that organize in some way around educational justice.

You have these very active parent groups, as well as these parent-school groups. Each school in Philadelphia has a Home and School Association—which is our PTA—as well as a School Advisory Committee or SAC, which is parents and community members and business owners. A lot of those groups also came into organizing these broader public conversations as a way to redistribute some of the power and knowledge of the planning process so that communities wouldn’t be the last to know about what was happening, what options were on the table.

This all sounds fairly similar to a lot of things that housing and community development groups get involved in, wanting to have more neighborhood input in a planning process. Were there any organizations of that sort that got involved in this process?

Yes. Within Our City, Our Schools in particular, there are a lot of community groups. There are groups of homeowners and property owners. There are groups that are for specific constituencies within the city. We have a pretty robust Philadelphia Student Union as well. Teachers were also involved. Our teachers union, particularly a more progressive wing of the union known as the Working Educators Caucus, were all involved.

Community quality of life was really centered in these discussions. I’m thinking about a group in the North Philadelphia, the high immigrant population area that I mentioned earlier. They were really concerned about school closures translating into gentrification. I felt that one of the most striking takeaways during these different meetings across the city was that people could draw a really straight line between a school closure and the construction of $400,000 townhomes in areas where that was not the median home value.

They saw this [process] as just a further coalition or growth machine that’s emerging between downtown and the school district. That was really a primary concern.

You also have concerns about segregation. There were parents—particularly in the growing neighborhood near the downtown, who didn’t like that there was a big racial divide across one street in Philadelphia—who said, “We’re going to build a middle school. Can we draw that catchment for the middle school across this racial divide so that we can have an integrated school and set that tone?”

These were discussions that were really thinking about “We have a lot of power in this conversation. How can we set a model for something that reflects the community’s needs?”

That’s really great. It seems like community development organizations that are building affordable housing or doing community planning would make a lot of sense to be in those conversations. If the school has to be closed, maybe it could be affordable housing at the least, right? Do you have suggestions for housing-focused community groups and how they could support their schools, or equitable school planning overall, in other places, particularly if there isn’t a planning process laid out for them to step into?

Yes, I think probably the most important thing when thinking about affordable housing or housing developers in public schools is that you really need to engage with the school as it is currently. You can’t think, like, “We’re bringing in this housing, what’s the ideal school that needs to be here?”

[Instead] just think about, “This school may be empty, but it’s serving as a pre-K center, it’s serving as an afterschool center, it’s serving as job training, it’s serving as a cooling center, it’s serving as a community gathering space.”

Think about that when you’re thinking about what you can bring to the school and what value that school is adding for your residents and for your communities. I think the main goal, the main takeaway, is starting to separate this very subjective idea of “school quality” [from] thinking about the actually existing role the school plays and how to strengthen that role for that community.

That makes a lot of sense. It also strikes me that they could maybe step into a conversation about school closure with some of those ideas you were talking about earlier, about other ways to use underutilized space.

Yes, the co-location is, I think, so critical. Key to why [the housing authority school is] so successful now was that thoughtfulness of “this is not just an asset to monetize and sell off to fulfill our bottom line . . . this is a key public good.”

One of the hardest things is breaking through to people who have no skin in the game of the public school. You really have to sell it as, like, “These are your tax dollars, this is what your tax dollars is going to support. You shouldn’t see a school closure as something that improves your property value. You should think about how can you improve the school and your property value at the same time.”

People don’t get upset when you close a public school, but they would get upset if you closed a public park. You have to think about them in the same way: you may not directly engage with it, but it serves a broader good and anchors your community.

I think that’s a wonderful place to conclude. Thank you.

Comments