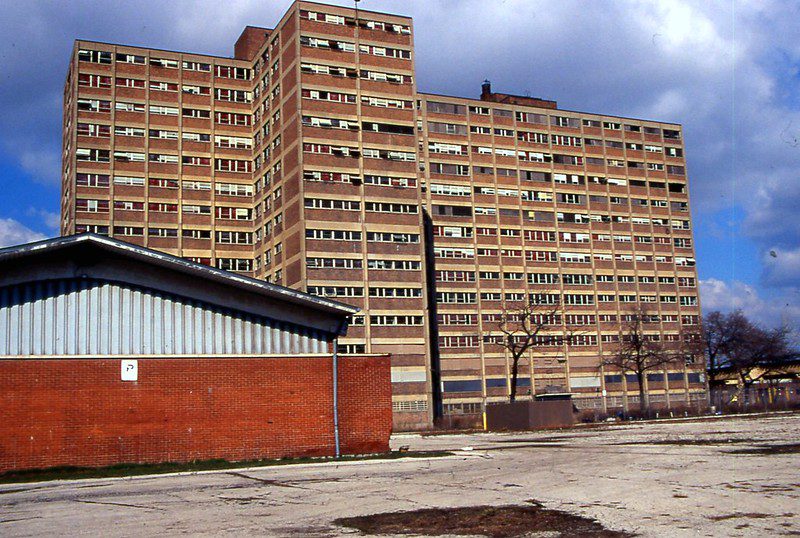

Henry Horner Homes was a Chicago Housing Authority public housing project that was demolished in the late 90s and early 2000s. Photo by David Wilson via flickr, CC BY 2.0

In September 2008, Hurricane Ike swept through the Gulf Coast island community of Galveston, Texas, battering the city with 110 mph winds and storm surges that flooded the streets. Three of Galveston’s public housing projects were damaged beyond repair in the storm, resulting in the Galveston Housing Authority demolishing 569 apartments.

More than a decade later, the housing authority is still working to replace every unit that was lost. The agency was set to break ground on a final project in that effort on Sept. 14. Ironically the ceremony was postponed because another storm, Hurricane Nicholas, was bearing down on the island. But once the project is complete, it will provide the final 174 units of deeply subsidized public housing that were lost to Ike, along with 87 units of moderately subsidized affordable housing and 87 units of market-rate housing.

The new apartments also hold the distinction of being the first in the country to use the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) new Faircloth-to-RAD program, which was rolled out in April of this year in an effort to get public housing authorities the financing they need to build extremely low-income housing.

Combined with the Democrats’ proposal to include $80 billion in funding for public housing’s massive backlog of maintenance needs, there is new energy around public housing in the U.S. and potential for public housing production to get a much-needed boost.

New Public Housing?

Faircloth is a reference to the Faircloth Amendment, a 1998 Congressional amendment championed by North Carolina Sen. Lauch Faircloth that capped the number of public housing units the federal government was allowed to fund. It prohibited HUD from funding construction or operation of any new units beyond the number public housing authorities had in their stock as of Oct 1, 1999. The Faircloth Amendment was meant to bar the expansion of federal public housing. But thanks to decades of disinvestment leading to demolition, natural disasters like Hurricane Ike, and programs like Hope IV that converted public housing stock to other uses, the number of public housing units has actually shrunk over the last 20 years.

By HUD’s latest count, America’s public housing authorities have 227,000 fewer units of housing now than they did in 1999—units they could rebuild without hitting the limits imposed by the Faircloth Amendment.

But even though they can legally build new units, housing authorities have built a negligible amount of new housing over the past few decades, according to HUD. Part of the problem is a lack of funding available for new construction. HUD’s public housing mixed-finance program can provide some funding, but development is expensive and public housing authorities must rely on outside financing such as Low Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC) and traditional debt.

Public housing commands meager rents, however, which provides little capital with which to repay construction debt. Tougher still, public housing operating subsidies are subject to the whims of Congressional budgeting, meaning some years housing authorities have less funding to work with. That makes it very difficult for housing authorities to make new construction financing pencil out. That’s where the RAD part of Faircloth-to-RAD comes in.

RAD is short for Rental Assistance Demonstration. It’s a HUD program launched under President Barack Obama that allows public housing authorities to convert public housing subsidies to Section 8 subsidies to attract private investment that can be used to fund long-overdue repairs and upkeep.

For Faircloth-to-RAD projects, HUD preapproves a RAD conversion to a housing authority that wants to build new units. The promise of future Section 8 subsidies plus HUD public housing mixed-finance program funds for construction make it easier for the housing authority to pull together the additional layers of financing. The program is also meant to streamline the process for housing authorities. Rather than seek HUD’s approval for construction of new units and then later seek the agency’s approval for RAD conversion, the housing authority submits a single application.

“The ultimate goal here is to maximize the number of households we serve,” says Tom Davis, director of HUD’s Office of Recapitalization. “Every Faircloth unit that comes online is a family who’s not worried about housing insecurity, is a family who might be safe from the risk of homelessness, is a family that can really think about opportunities for their kids and opportunities for improving their job prospects instead of worrying about where they’re going to sleep in a week.”

“I’ve been doing this a very long time and we’ve never been in a position to have a conversation about building more,” says Susan Popkin, director of Urban Institute’s Housing Opportunities and Services Together initiative. “For so long, public housing has been viewed as the poster child for the failure of social welfare programs. Now we’re in a position where we’re saying we really need this and we need to have it be sustainably affordable and sustainably maintained and managed in order to house extremely low-income people who aren’t being served by the private sector.”

The program has drawn support from public housing trade groups such as the National Association of Housing and Redevelopment Officials (NAHRO) and the Council of Large Public Housing Authorities (CLPHA), as well as housing advocates such as National Low Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC).

Davis says the agency has seen marked interest from housing authorities in putting Faircloth-to-RAD to work. “Over the last 20 years, people weren’t building [new public housing] because it has been very hard to do. Now, it’s amazing how many housing authorities have approached us in the last six months about building Faircloth units. It’s working.”

Reaching the Promise

Public housing authorities throughout the country could build about 227,000 units of new housing, a small number relative to the 6.8 million units of extremely low-income housing the National Low Income Housing Coalition estimates is needed. But taken on a city-by-city and county-by-county basis, the impact could be significant. For instance, the Chicago Housing Authority has lost and failed to replace 19,543 units in the last three decades and could build up to that many new units. The New York City Housing Authority could build 12,155. New Orleans could build 10,347 and Memphis could build 4,582.

“In Washington, D.C., they have more than 2,600 units they could [build],” says Popkin. “2,600 units of permanently, deeply affordable units would make a huge difference. That would be a wonderful outcome.”

As a bonus, says NAHRO policy director Georgi Banna, new housing production can be a boon to local economies. “This can also be a great economic catalyst for local communities. Jobs in the housing industry are good-paying jobs for local residents and local communities that can be funded through HUD. It can be a win-win on both the housing and economic side.”

Of course, not every housing authority has significant Faircloth capacity nor will every authority build every unit it can. Part of the problem is that both the mixed-finance construction program and RAD are fairly complicated federal programs that some underfunded, understaffed housing authorities might not want to wade into. Public housing industry experts expect to see primarily larger housing authorities, especially those that have already converted units through RAD, building new units through Faircloth-to-RAD.

“The more complex it is, the more moving parts there are, the harder it is to implement and manage,” says CLPHA Executive Director Sunia Zaterman. “That would be our overarching concern and advice. . . . HUD needs to come out with a product for the practitioner that is seamless, if you will, that doesn’t have overlapping and conflicting regulatory structures.”

Ethan Handelman, deputy assistant secretary for HUD’s multifamily program, says the agency is working to shape and revise Faircloth-to-RAD to address the issues housing authorities have raised so far.

“The ideal outcome is that it’s seamless,” Handelman says. “That if a housing authority wants to develop additional units under its Faircloth limit there is an easily understood and accomplished path to have that go through a RAD conversion that doesn’t entail any duplication of environmental reports or other processes.”

Concerns About RAD

RAD itself has drawn criticism and concern from housing advocates and tenants groups.

In some RAD conversions, the housing authority retains ownership of the units and simply receives a Section 8 Project-Based Voucher subsidy instead of public housing program subsidies. In other RAD conversions, a nonprofit entity can take ownership of the units and receive a Section 8 Project-Based Rental Assistance subsidy. It is that latter category of ownership model that most worries advocates.

On paper, RAD tenants have the same rights and protections as public housing tenants. But in practice those rights and protections haven’t always been enforced. The National Housing Law Project has documented instances of RAD tenants being evicted without proper notification or grievance procedure, property owners violating tenants’ right to remain in the property after eviction, and other issues.

“Oversight needs to be a focus,” says Popkin. “HUD needs to make sure there aren’t big mistakes and that they don’t repeat the kinds of problems of the past, like tenants being displaced and nobody tracks where they went.”

RAD property owners must renew their contracts after the 20-year term is up. But some tenant advocates still worry private investors will fight to not renew to get market-rate rents.

“There’s always that scary bit about the nonprofit or the LIHTC general partner, what are they going to do in the long run? Will it go hardcore privatization? We just don’t know,” says NLIHC senior adviser Ed Gramlich.

Still, even a self-professed RAD skeptic like Gramlich supports the Faircloth-to-RAD option.

“It’s a creative and good idea,” he explains. “My same concerns about RAD could translate over to the Faircloth-to-RAD situation. The thing is, I’m not so worried about that because these units don’t exist and they will not exist ever unless somebody can take advantage of the Faircloth availability. I’d be willing to take a risk on this option just for the sake of hopefully gaining some deeply affordable units around the country.”

An $80 Billion Boost

As HUD gets its Faircloth-to-RAD program off the ground, the Biden administration is pushing Congress to include $80 billion in public housing capital funding. Congress has underfunded public housing capital needs for so long it is estimated to cost at least that much just to address all the repairs, upgrades, and replacements America’s public housing needs.

The $80 billion in capital funding is separate from Faircloth-to-RAD. That money will be used to fix existing public housing and perhaps build some new units to replace those that have deteriorated beyond repair. But it’s part of a broader recognition by Congress and the Biden administration that public housing plays a key role in the country’s housing ecosystem.

“Who would say things would not be better with $80 billion?” says CLPHA’s Zaterman. “Having that amount of money go through the capital fund is a statement that we’ve chronically underfunded our public asset. That’s very important. But it only deals with the properties we have already. It’s not addressing the fact that we’re only meeting the needs of one in five low-income renters with housing assistance.”

Next Step, Nix Faircloth?

Since units that pass through the RAD program still count toward the Faircloth limits, Faircloth-to-RAD can only go so far toward expanding public housing. To truly revive the public housing program, supporters say Congress needs to get rid of the Faircloth Amendment entirely (something Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez proposed doing in February 2021) and commit funding for the construction of new units.

“Get rid of Faircloth,” says Zaterman. “It’s ridiculous. Lauch Faircloth was in the Senate for one term. And this is probably the most notable thing he ever did—undermine the public housing program.”

Until then, Faircloth-to-RAD is a small tool, working within the constraints set by Congress, to rebuild the public housing we’ve lost.

Very informative article and interesting update on the RAD stuff, but I think it’s a major problem that you’re referring to this as “public housing.” “Public housing” usually refers to the housing that is built *and managed* by public Housing Authorities, and I don’t think this term should be used for RAD housing. It’s privatized “affordable housing” that is also subsidized by local HAs.

That comment is correct and an important distinction. RAd falls between 24 CFR 964 and 24 cfr 245. technically under 245, but HUD has issued Notices to the PIH ( public and Indian Housing part of Housing) grandfathering in much of 964, I.e., $25.00 per unit for duly organized tenant Associations. So it is confusing, but definitely NOT still ‘ public housing” I get it from mayor’s Office of housing all the time, “but, you’re not IN public Housing anymore.”