Photo by Daniel Latorre via flickr, CC BY 2.0

“Participatory budgeting is democracy in action,” proclaims a recent email to constituents from Brad Lander, a progressive city councilman in Brooklyn, New York.

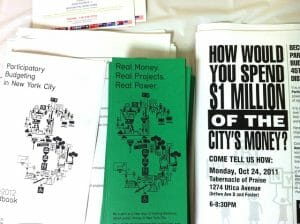

We hear a lot of claims of this kind from proponents of participatory budgeting, a process that has been adopted throughout the U.S., which enables citizens to vote on how part of a municipal budget will be spent. New York City Council’s website touts participatory budgeting as a way to give “real power” to people who have never before been engaged in the political process. Participatory Budgeting on NYC’s Twitter account offers an irresistible invitation: “YOU Decide How to Spend Taxpayer Dollars!”

Just like a focus group or any mechanism intended to give us a voice, participatory budgeting can feel a lot like democracy. It offers a glimpse of how a more civically engaged society might work. But it’s also a distraction from the actual mechanisms of power, and can reinforce or even worsen existing inequalities.

Celina Su, a Brooklyn College political scientist who has studied the matter, observes that the process tends to favor those with social power. Her findings show, as you might expect, that people with resources are more likely to lobby for projects that serve their communities, and to run successful campaigns. My own Brooklyn City Council district, located not far from Lander’s, includes many poor neighborhoods and poor people, yet more than half the projects on the ballot this year served gentrifying populations. Last year, a proposal to improve a garden in a local housing project lost by just a couple thousand votes. On Staten Island last year, all three proposed improvements to a housing project were voted down. In Lander’s district, all of the winning capital projects served well-off or gentrifying neighborhoods.

There might be ways that such inequalities could be mitigated to make the process fairer. Officials overseeing the process could do more outreach in poorer neighborhoods and place more curbs on the participation of the rich and savvy. But an even more intractable problem, as Gianpaolo Baiocchi, a scholar who has studied participatory budgeting, has observed, is that these contests over relatively small amounts of money can distract activists from trying to gain real power in the political system.

In my district, all of this year’s proposed projects were necessities, not just stuff that somebody thought might be cool. Making an elementary school building safer should not be left up for a vote, and shouldn’t have to compete with fixing the electrical system at my beloved branch library. The fact that both were viewed as optional and were even on this ballot, pitted against one another, reflected a lack of popular power. In a rich and prosperous city, everyone’s needs should be met.

It’s great that Lander’s district voted to fix “derelict” (the wording on the ballot) sinks in a kindergarten classroom, but why should such an important priority be up for a vote? The same could be said for making a branch library in Queens more accessible to people with disabilities (an item on last year’s ballot). Last year, many of the participatory budgeting projects throughout the city involved air conditioning for public school buildings, all of which stay open through June, and many used for summer school classes. The public voted to fund some of these, and not others. Yet, on some summer days, New York City temperatures reach well over 90 degrees. Why choose whose children must suffer in sweltering heat? It’s horrible to hold a “Hunger Games” process to decide whether to make a school playground safer and more accessible, or to resurface a public soccer field. These things should simply be done, without any self-congratulatory gimmicks or rigmarole.

The reason these kindergarten sinks are in such sorry condition in the first place is because of a regime of austerity imposed upon the New York City public sector ever since the 1970s, by real estate and finance industry elites who don’t want to have to pay higher taxes, a status quo that conservative Democrats and Republicans in the state capital are happy to protect. The only solutions are electing more people who favor redistribution into office in Albany, and organizing to build power for the 99 percent, whether through tenants’ groups, unions, or left political parties.

While participatory budgeting originated in Latin America in the context of such ambitious efforts, Baiocchi and Ernesto Ganuza observed in a 2014 paper, in the United States, it has been completely disconnected from any left institutional projects.

“Choice”—as we know from the past two decades of so-called education reform— should not make the poison pill of austerity any easier to swallow. Neoliberal policymakers think that we should be happy that we get to choose our children’s schools, even though they are all underfunded. Ultimately, participatory budgeting is a similar scam. The pleasure of making choices can’t make up for stark inequalities and scarcity. While getting to vote on the budget is fun, it doesn’t come close to giving citizens “real power”—or even distributing the crumbs of influence equitably.

One caveat is that in the context of a well-funded public sector that met every community’s basic needs, participatory budgeting would be a wonderful way to encourage inventive policy-making. A lot of innovation can come from engaging people who are outside the policy world. Some of the winning projects in Lander’s district this year—for example, a study of endangered bats in Prospect Park—were exciting ideas that will probably never correspond to any specific line item in a city budget. The participatory budgeting process is one way to find funding for such ideas, and involve the public in thinking them through. But no way should we be voting on whether to make an elementary school or playground safer, or worse, deciding which kids deserve this safety more.

Perhaps, then, the problem is not necessarily with participatory budgeting as a concept, but with its broader, unequal, and stingy context, in which so many basic needs are left unmet. The frisson of making proposals and choices may have its place, but let’s please tax the rich and fix everyone’s sink.

Participatory Budgeting is a testament to the strength, not the failure, of American democracy.

As a high school senior who has spent the last few years working intensely on the PB process facilitated by Council Member Lander in District 39, I have seen an unparalleled social and political value in the PB process.

From the outset, the notion that we should “fix everyone’s sinks” fails to capture the essence of PB. Of course, there are systemic issues and endemic inequalities in every city—especially in NYC, where there is an absurd level of socioeconomic inequality—that PB cannot remedy. But that’s not PB’s goal; the process does not present itself as the end-all-be-all solution to government negligence, or misallocation and lack of public funds.

You do acknowledge that “perhaps…the problem is not necessarily with participatory budgeting as a concept, but with its broader, unequal and stingy context, in which so many basic needs are left unmet.” I agree with this sentiment. Government dedication to remedying systemic inequality is important; in NYC, we could start with implementing a millionaires’ tax. But the systemic issues, like housing and school segregation, would not be solved with the mere implementation of this tax. They could never be solved overnight, and they could not even be solved over the course of a few years. Solving systemic issues requires gradual systemic change—change that takes place over decades and centuries. To simply suggest that we “tax the rich and fix everyone’s sink” is an exceedingly idealistic and abstract conception of how we would go about making such change. Even with that kind of progressive tax change, we would have to critically examine the expenditure of our official city and state budget, which are not, incidentally, where PBNYC money comes from (city council members individually allocate a portion of their own discretionary funds to the PB process in their district).

And making real systemic change is certainly not in conflict with the PB process. While we’re trying to address such larger issues, why should the public not have a say in where they want to start? PB can accomplish small change, the kind that impacts the daily lives of local residents, in a matter of years. And it’s change the public wants to see—the top vote-getting projects are implemented. So yes, it would be nice if everything could be fixed all at once. But since that’s not realistic, why should we as constituents not have the chance to express our priorities and demand a quick fix on a smaller scale? We don’t give up the larger fight for systemic change in doing so; we don’t succumb to a “distraction.” Rather, many of us become more engaged in the fight for a truly just, equitable, and democratic society!

One of the projects on the District 39 PB expense ballot last cycle was for diversity counseling in the district’s middle schools. Would this solve school segregation? Of course not! But it at least reflects an attempt by local residents to amplify the conversation on the importance of integrating NYC schools, a conversation that many of our policymakers are unwilling to fully have (Mayor de Blasio won’t even call NYC schools “segregated”). And at least here in District 39, having the project on a PB ballot did spur important conversation.

Already, the U.S. has one of the lowest records of voter engagement among developed Western nations. Many states exclude former felons from the voting process and implement measures such as voter ID laws that suppress, rather than elevate, voter engagement. By contrast, PB invites all district members, regardless of citizenship status or federal/state voter registration, and even from the age of eleven, to participate in civic decision-making and cast a ballot. It’s not idealistic to say that this represents what democracy’s all about because it does. The process is meant to be equitable and inclusive, to embody the values we wish to see in our government and model their implementation. It also connects neighbors within the same council district who might otherwise have never spoken, much less worked together to develop a proposal for a storytelling garden at the local library.

Admittedly, PBNYC has its flaws. District 39 continues to serve as a model for the successful PB process in many ways because it has the advantage of political and social resources other districts don’t. But it was also one of the first districts to participate in PBNYC, which was originally introduced by Council Member Lander and his colleagues, and thus has much more developed PB process than other NYC council districts. For instance, it has both a capital and expense component to its PB process, unlike other districts. It also has an established District Committee overseeing its PB process, and Council Member Lander intentionally allocates a sizable portion of his discretionary funds (over $1.5 million total) to the process. Rather than shun the success of PB in District 39, we should learn from the way its process works and call upon District 39 PB advocates to organize with other districts in need of more support and resources.

You also note that “in Lander’s district, all of the winning capital projects served well-off or gentrifying neighborhoods.” Certainly, there can be a disparate distribution of project funds in District 39, just as there is a disparate distribution of wealth and resources. That’s something the District 39 PB process needs to be held accountable for, and that I know from experience those supporting this PB process are working to fix, but abandoning the process if far from the solution to this issue. Also, two cycles ago, the top vote-getting capital project was providing mobile showers for the local CHIPS homeless shelter. That’s a true measure of what PB can accomplish—residents from “well-off or gentrifying neighborhoods” recognizing a need for a more equal distribution of resources in their community and wanting to serve those without such access.

To end, I will revisit this point: “In a rich and prosperous city, everyone’s needs should be met.” Well, yes—of course! That’s a grand and legitimate statement, just not one backed up by a poor evaluation of a local democratic process that has worked to empower NYC residents in the midst of sweeping inequalities.

I can’t speak to the author’s experiences with PB in Brooklyn, but in cities such as Austin it would be a major step forward. Our city is currently embarked upon a once-in-a-generation rewrite of our 1,500 page land development code, and city officials and their urbanist contractors and collaborators have completely botched the process and produced a neoliberal Frankenstein’s monster that nobody likes and that has very little buy-in from the man or woman on the street. At issue is who gets to decide the future of the city? Well connected insiders, developers or communities? Structural attention to PB would have at least forced some of these officials out of their smoky and slimy backrooms into actual conversation with neighborhoods, especially in poor and pigmented areas such as Montopolis that have been targeted for aggressive gentrification.

I’m in agreement with Ilana Cohen: it is true that PB is not a solution for inequality, but I’m not aware of anyone who ever said it was. Is it a distraction from larger left organizing? Perhaps. But it can also be a springboard for greater community participation and political empowerment, especially in places south of the Mason-Dixon line.

This article would have been strengthened by at least a mention, if not actual examination, of examples where PB was considered to be a success. When combined with community benefits agreements and other organizing, PB can be an effective tool that helps set the stage for the coalition-based mass political action necessary for deep (and hopefully permanent) institutional change.