Postcard image by Jim Griffin via Flickr, public domain

Land use regulation—the seemingly mundane world of floor area ratios, height limits, front yard setbacks, and, especially, zoning—has been thrust into everyday political debates about the future of our communities. Often, the conversation is focused on making housing more affordable, but sometimes the racist history of those regulations is invoked, and rightly so!

When Minneapolis, for example, ended exclusive single-family zoning in 2018, permitting duplexes and triplexes to be built on most parcels in the city, the mayor and city council asserted that the revision was intended to begin to address the history of racist intent embedded in land use regulation.

But not everyone is convinced that changing land use regulation would be a significant step toward closing the racial wealth gap. David Imbroscio lays out an alternative view in a 2022 Shelterforce opinion piece in which he asserts that it is racist values themselves, particularly in the housing market, that produce racial wealth inequality, rather than the specific policies that those values inspired.

Imbroscio eloquently explains that since markets are simply expressions of value, if what we value is shaped by racism, then our markets will produce racist outcomes. In America, with its persistent anti-Blackness, houses and neighborhoods inhabited by Black residents are valued lower than houses and neighborhoods inhabited by white residents. This is one of the reasons Black homeowners do not build equity in the same way that white homeowners do, which itself is one of the foundations of the racial wealth gap. That gap cannot, Imbroscio argues, be closed by making changes to policies that would increase access to the housing market, because the housing market itself reflects racist values that persist.

While it is true that this type of policy change would be insufficient, Imbroscio underestimates the ways in which residential segregation continues to be directly enabled by land use policies with racist origins. Modern-day land use regulations shaped by racism are the very definition of institutionalized racism. They allow racism and anti-Blackness to be perpetuated without participants consciously holding racist or anti-Black values. In addition, racist land use policies make it easier for residents who do hold racist values to act upon them.

We can use single-family zoning as a lens to understand this process. Imagine a community where a small but committed group of white people refuses to live in the same neighborhood as Black or Latino residents—they do not want their children playing with children of color, and they believe their schools and public safety will benefit from living in a racially homogenous community. We’ll call these the segregationists. It has been shown that even a mild preference for living among neighbors who share the same race can lead to dramatic patterns of segregation through population sorting. On top of this, our imaginary group of segregationists is so dedicated to their racist views that they are willing to pay an extra cost for housing in a segregated neighborhood. In a society with significant racial wealth and income gaps, the high cost helps to maintain the racial homogeneity of the neighborhood, and thus its perceived value (as Imbroscio explains, the whiteness of the residents is in and of itself valued). The local government enhances this perception by treating the neighborhood a bit better than surrounding neighborhoods. The roads are repaved more frequently, a park is built within walking distance, and more-experienced teachers are allocated to the schools.

Now imagine that an enterprising developer decides to buy a house in this neighborhood and replace it with a quadplex—four single-family units connected to each other. Each of these units is much less expensive than the other houses in this neighborhood. Now, people who are less committed to the segregationist worldview (and those who have lower levels of wealth) may be more likely to buy a house in this neighborhood. Black and Latino families may move into these new units, giving them access to the good schools and safe streets that the segregationists cultivated. Despite historical patterns of white flight, recent evidence suggests that today, integrated neighborhoods are likely to stay that way, as new residents build commitment to their community.

If we go back in time and implement a single-family zoning regulation for our segregationist neighborhood, however, this transition does not play out.

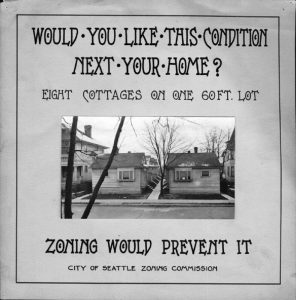

Photo of a 1922 poster from Seattle Municipal Archives, via Flickr, CC BY 2.0

Single-family zoning was first developed as a strategy to promote racial segregation in the early 1900s, but this does not make its power any less significant today. In fact, if other areas of the city do not have exclusively single-family zoning, the segregationist neighborhood will become ever more expensive and attractive to segregationists (and easier for politicians to target with benefits), eventually leading to dramatic increase in housing wealth for these homeowners. Public policy should not be used to subsidize segregationists’ opportunities for wealth building.

At the same time, an absence of single-family zoning (or its removal) should not be viewed as a panacea for directly building wealth among people of color. Homeowners of color continue to face biases that affect their ability to benefit from their investment in the same way as white homeowners. In fact, in certain circumstances, the presence of Black and Latino families can lower housing values at the neighborhood level.

Because racism underlies policies like single-family zoning, simply removing the policy will not remove the racism. The racism can reappear in new ways. That does not mean that we should allow the policies to stand, though. It means we must take stock of all of the policies that have been implemented for racist ends or which are used for that effect today. Other land use regulations, such as open-space preservation or historical overlays, large lot zoning, and parking minimums can have effects similar to those of single-family zoning. There is even substantial variety within single-family zones: lower dwelling units per acre requirements are more likely to have segregation.

It is also important to document the ways in which racist land use regulations contribute to ongoing patterns of inequality. Imbroscio is right that redlining didn’t produce racial inequality in America all by itself, but it did play a role. As a result of the Federal Housing Administration’s (FHA) risk-averse approach to mortgage lending, the vast majority of loans went to white borrowers in new suburban homes. The racist values Imbroscio outlines played a powerful role in the valuing of housing and assessment of risk, and in the long run, pushed down home values and homeownership rates in neighborhoods that were denied access to federal funds. The FHA did not invent these standards of worth, but it lent the weight of the federal government to codifying them.

Research shows that various land use regulations can change both the demographics of neighborhoods and the value of properties, and in turn, lead to segregation. Segregation causes a number of adverse impacts on Black people in the U.S., contributing to higher poverty rates, lower high school and college graduation rates, higher imprisonment rates, and higher rates of single parenthood. Segregation additionally leads to lower intergenerational mobility for low-income children. Ultimately, there is no policy tool that can be used to change racist valuations in the housing market, but we do have policy tools to lessen segregation, which has real world effects. Eliminating restrictive land use regulations is one place to start.

Legal racial segregation was abolished in the sixties but the social effects remain, primarily caused by white fear of crime and bad schools. Conservative judges have interpreted the laws to protect these behaviors. De facto segregation by race and class can be self sustaining, and things like zoning contribute, as do the location of services like shops, quality schools and health care, and the quality of the safety net, including policing. There is no magic bullet to dealing with this complex problem, particularly given the rising inequality in a society that feels like a zero sum game or worse to so many. Creating more housing and doing it in diverse settings would certainly help, as would investing in quality education everywhere.

Your argument rests on the statement “people who are less committed to the segregationist worldview (and those who have lower levels of wealth) may be more likely to buy a house in this neighborhood” Is there any evidence that this is so? The end user cost for a triplex constructed under Minneapolis’ new zoning law will be determined by the market not by the cost of construction. In a wealthy neighborhood that cost will not be low. Why would people of lower wealth be attacked to it.?