This article is part of the Under the Lens series

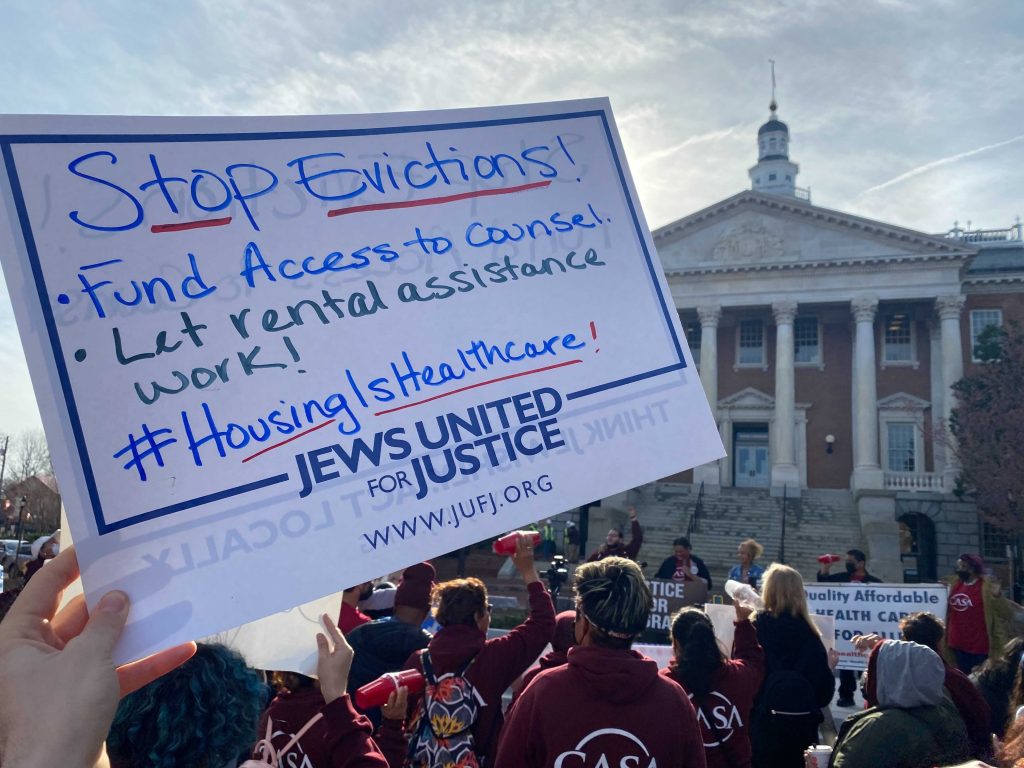

A sign at a rally at the Maryland State House earlier this year. Photo courtesy of Renters United Maryland

In 2021, the Maryland General Assembly passed a bill guaranteeing access to counsel for low-income tenants facing eviction. While it was a key win for the state’s housing justice advocates, a companion bill to fund it failed to pass, leaving the new law stuck in limbo. Advocates felt utterly deflated.

“It was extremely frustrating to have a law with no money to implement it,” says attorney Matt Hill, team leader for the Human Right to Housing Program at the Public Justice Center, a Baltimore-based multi-issue legal advocacy group.

The Renters United Maryland (RUM) coalition, of which Public Justice Center is a founding partner, had campaigned for a large slate of tenant protections that year, and its members were keenly disappointed when nearly every bill they’d supported failed to pass.

Fast-forward one year, and the 2022 legislative session outcome was considerably brighter. RUM again advocated for numerous bills, and this time legislators passed almost all of them—including one that allotted funding for the Access to Counsel in Evictions Program, for which advocates can finally savor their victory.

“Passing the access to counsel in eviction statewide was a victory in itself, but setting forth that funding path was a substantial victory in actually having this right,” says Public Justice Center attorney Charisse Lue, who served on a task force set up in 2021 to study implementation and funding for the new law.

A Multiyear Organizing Process

The Maryland effort illustrates how winning tenant protections can be a multiyear effort. The 2021, 2022, and upcoming 2023 campaigns are all part of a long game that RUM began devising five years ago, says Zafar Shah, Public Justice Center attorney and RUM coalition co-coordinator.

‘Real estate groups, multifamily commercial lobbyists, and the like are always working statewide . . .So we deliberately and transparently set out to be a counterbalance to that.’

“Renters United Maryland’s strategy was to be a factor in the legislative process over the long term,” says Shah. “This makes it different from prior state-level movement-building.”

He explains, “A lot of players would come to the fore with local interests or with a constituency of a certain legislator in a certain district. But that’s not what our adversaries do—real estate groups, multifamily commercial lobbyists, and the like are always working statewide. They’re not looking at their political agenda in such a granular way; they’re building relationships in Annapolis. So we deliberately and transparently set out to be a counterbalance to that.”

Shah describes a recent gradual shift in mindset on tenant rights in a state government that’s typically been far more friendly to landlord interests than tenant protections.

“I’ve been doing this work since early last decade, and it wasn’t until about 2017 and 2018 that we were able to make any headway with legislators on tenant issues,” he says.

A convergence of various forces served to highlight tenants’ struggles even before the pandemic—among them Matthew Desmond’s book Evicted, published in 2016, and major institutions marking the 50th anniversary of the Fair Housing Act in 2018. Shah cites these as helping to change legislators’ awareness little by little and feeding a groundswell of grassroots action. Then, COVID-19 brought a new surge of need and political energy both nationally—with congress people sleeping on the U.S. Capitol steps to protest the lapse of a federal eviction moratorium—and locally.

“The last two years have been a real draw for tenants to get involved, and there’s been a resurgence in worker organizing,” Shah says.

The Difference a Year Makes

What made the 2022 legislative session more successful than 2021? There’s no short answer.

RUM didn’t make a major shift in organizing strategy between 2021 and 2022, Shah says, but it grew its base of support among tenant groups and local government officials. And, importantly, stakeholders came to a consensus that, given the urgency to pass eviction-delay measures, RUM had to be willing to negotiate.

“We really negotiated as much as possible to meet landlords and real estate lobbyists in the middle,” he says, which led to some bills being easier for legislators to pass in the 2022 session.

One of the obstacles in 2021 was that the attorney general had placed a high priority on a bill that would fund the access to counsel program by instituting a $50 surcharge on landlords for each failure-to-pay eviction filing. This drew stiff opposition.

“That cost-of-eviction increase was really polarizing,” Shah says, “and there was so much attention to that one bill that some others got scrapped along the way.”

In the end, the eviction fee surcharge bill was narrowly defeated, leaving the access to counsel program unfunded. Just as devastating, none of the emergency anti-eviction protections the advocates had sought as crucial aid in the pandemic passed.

‘We’re always at a disadvantage. Many of the legislators are landlords. They themselves have financial interests in property and in eviction.’

Advocates were left embittered by these failures, but Shah notes a silver lining of sorts: Some legislators who had been on their side realized their failing and set out to make things go differently the following year.

“Some of them reached out to us to say, ‘I’m sorry, we kind of messed up. What’s your priority going into the next session?’” Shah says. “Our message to them was, ‘You had a way to prevent these problems that renters are experiencing, and you fell short. We need you to do more.’ And so in 2022, key legislators made our agenda a priority.”

In 2022, the conversation shifted away from the prickly eviction filing surcharge toward other means of funding. That helped to secure passage of bills to fund the access to counsel program from the state budget in FY 23 and other sources, and allow other bills to receive more attention.

Another effort that failed in 2021 was a measure deemed critical by advocates—allowing eviction delays for tenants with pending rental assistance applications. At that time, Shah says, many legislators thought vaccines would end the pandemic and that federal COVID relief funding would fix a lot of eviction issues. But clearly, that was not so, and in the last half of 2021, almost 700 Maryland families per month were evicted, even though many had rental assistance applications pending, according to the Public Justice Center.

“So in 2021, there wasn’t interest in fighting the real estate lobby in the hopes of creating a new model for rental assistance and eviction diversion,” Shah explains. “But by 2022, the end of the CDC moratorium and the disconnect between local rental assistance programs and the courts opened people’s eyes.”

The second time around, that fight was more successful, to a point. A bill to pause eviction proceedings for tenants awaiting rental assistance passed both chambers—but was then killed by Gov. Larry Hogan’s veto.

A second bill that successfully passed in the General Assembly after failing in 2021—requiring landlords who file evictions to prove they are properly licensed—also fell to the veto ax.

What’s Next?

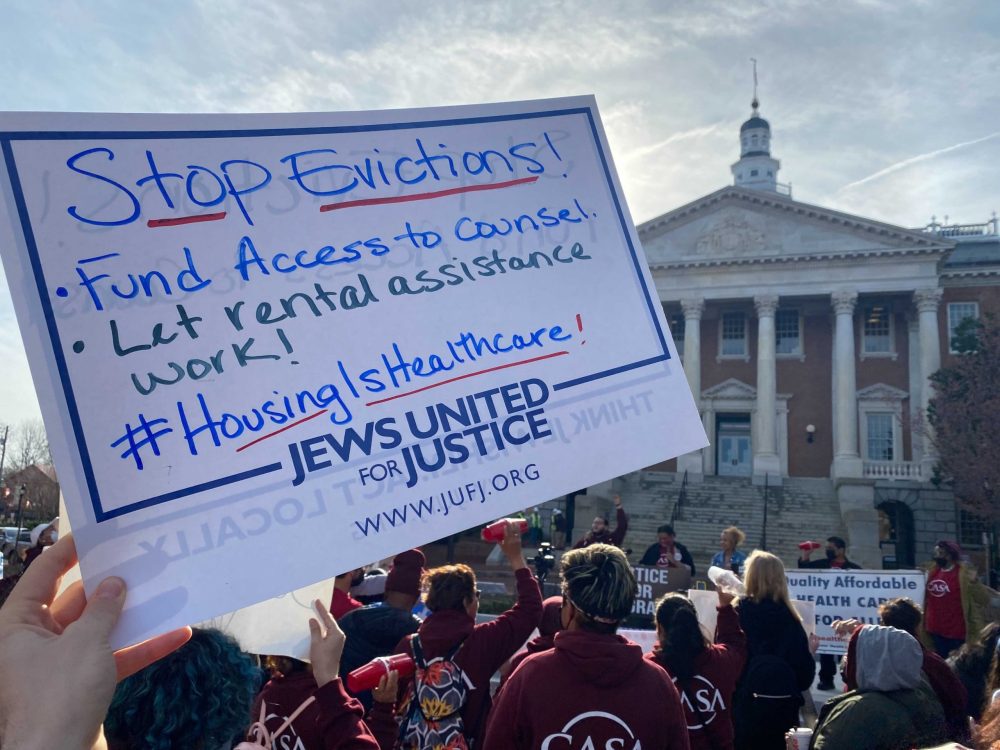

The Renters United Maryland coalition rallies to support housing rights earlier this year. Photo courtesy of Renters United Maryland

Advocates are gearing up for the 2023 legislative session, vowing to revisit unfinished business like the vetoed bills. A statement on RUM’s website sums things up succinctly: “Vetoes of legislation to improve rental assistance, reduce evictions, and weed out slumlords from our courts leave us with more to do. We’re up for the fight.”

Shah expects momentum to continue and new goals to emerge, especially as rents have continued to increase. “The inability to pay rent is hitting more and more people,” he says. “To date, we hadn’t prioritized rent stabilization—that’s the hardest fight you can take on—but the organizers and renters are now working for that.”

It’s a cyclical path, advocates know, and often uphill. Reflecting on the 2022 session, Shah says, “We’re always at a disadvantage. Many of the legislators are landlords. They themselves have financial interests in property and in eviction. In the negotiation room before a hearing, there’s a very vocal faction saying, ‘You’re going to destroy housing, hurt tenants, hurt landlords.’ So to get this far is important and successful.”

|

|

These programs matter no doubt about it. Protecting tenants from unethical actions. However, in those thousands of thousands of cases where tenants are negligent, cause intentional vandalism….they are silent. Holding greedy, unethical landlords or slum lords accountable: GRAND. Giving a pass to vandals who destroy property: Unacceptable. This I will fight