Photo by Lenny DiFranza via Flickr. CC BY-SA 2.0

This year marks an important milestone in federal housing policy. Homes financed through the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program, our nation’s largest affordable housing production program, are reaching the end of their federally mandated 30-year affordability restrictions for the first time. Over the next decade, more than 387,000 LIHTC units could reach this milestone. Many, if not most, of these homes will need reinvestment to preserve their affordability, quality, or both. The growing need for capital subsidies to address this preservation challenge should already be obvious to anyone involved with affordable housing. However, expanding rental assistance like Housing Choice Vouchers (HCVs) is an equally important policy goal that can help ensure the security and well-being of tenants, and ultimately contribute to preservation.

LIHTC Background

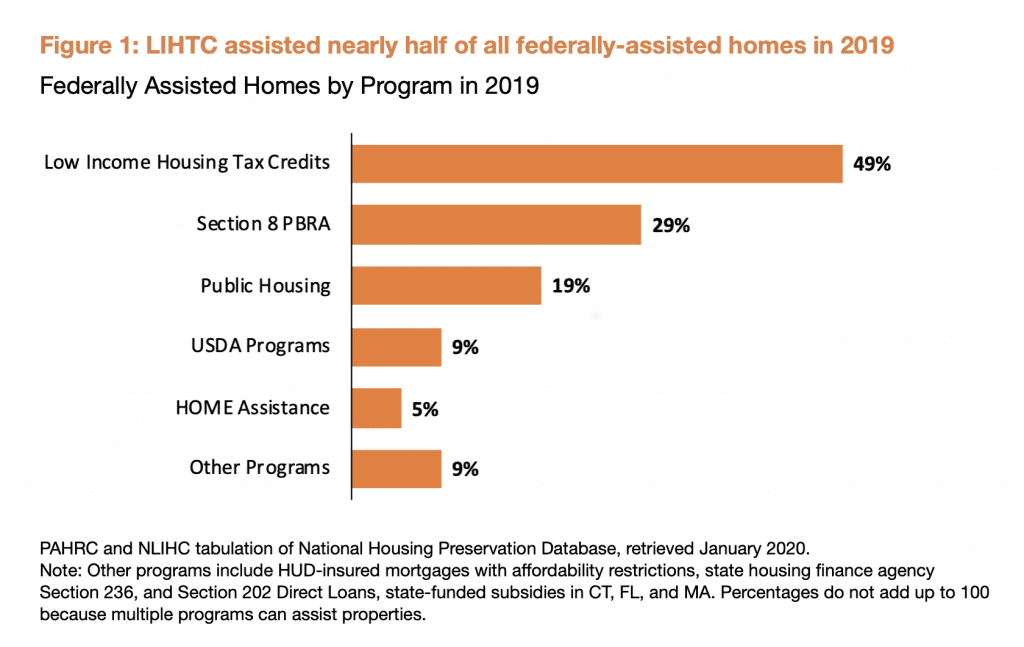

LIHTC is the largest affordable housing production program in the United States. A new report from the National Low Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC) and the Public and Affordable Housing Research Corporation (PAHRC) finds that approximately 2.4 million rental homes were participating in the LIHTC program as of 2017, with the program supporting 49 percent of all project-based federally assisted rental homes (Figure 1). Section 8 project-based rental assistance (Section 8 PBRA) supported 29 percent of the stock, public housing supported 19 percent, and the USDA loan programs supported 9 percent. The LIHTC program, however, often only provides partial funding for construction or rehabilitation. Approximately 49 percent of LIHTC units receive additional federal project-based subsidies.

The LIHTC program can serve tenants from a range of income groups, but often serves much lower-income households than many people realize. Under federal law, at least 20 percent of units in a LIHTC property are reserved for tenants with incomes at or below 50 percent of the area median income (AMI), or at least 40 percent are reserved for tenants with incomes at or below 60 percent of AMI. Alternatively, units can serve tenants up to 80 percent of AMI so long as the average income served by all units in the project is no more than 60 percent of AMI. In some cases, developers elect to set aside and make affordable LIHTC units for incomes lower than 50 percent or 60 percent of AMI.

[RELATED: Losing Nonprofit Control of Tax Credit Housing?]

In other cases, LIHTC owners rent to tenants with incomes below their units’ income-eligibility and affordability thresholds. A tenant with income at 20 percent of AMI, for example, may live in a unit affordable at 50 percent of AMI. According to the most recent HUD data on LIHTC tenants, more than 43 percent of LIHTC households reported incomes at or below 30 percent AMI, and 62 percent reported incomes below 40 percent AMI. LIHTC owners may do this for a variety of reasons: they may be unable to attract tenants with incomes closer to the eligibility threshold; few alternative housing options exist for the tenant, or the tenant is willing to incur a cost burden to access a high-quality unit or one that is in proximity to needed amenities.

The lowest-income LIHTC tenants can be particularly vulnerable to cost burdens and housing instability, because of the way rents are structured in the program. LIHTC rents are not based on a tenant’s income as they typically are with HCVs or public housing. LIHTC rents are instead set at 30 percent of a unit’s income-eligibility threshold. This means a tenant with household income below the eligibility threshold for their unit will often be cost-burdened. Rents can also fluctuate based on changes in AMI, since AMI is used to determine the eligibility thresholds for units. Rent does not change based on a tenant’s income. Of course, any restrictions on eligibility or rents are lost if a LIHTC property leaves the program.

The Case for Rental Assistance

Even before preservation challenges arise, rental assistance protects the lowest-income LIHTC tenants from housing instability by providing affordable rents based on their personal incomes. Tenants with HCVs contribute a percentage of their incomes toward rent, while the voucher pays the remaining amount. One study estimated that 78 percent of LIHTC tenants with incomes below 30 percent AMI utilized rental assistance to afford their rent. In contrast, 58 percent of LIHTC tenants with incomes below 30 percent AMI who had no rental assistance were severely cost-burdened, paying more than half of their income for their housing. Rental assistance could help protect tenants with fixed or insufficiently growing incomes from unaffordable rent increases arising from rapidly increasing AMIs on which LIHTC rents are based. A 2018 report by the Seattle Women’s Commission and the King County Bar Association, for example, found that AMI increased by nearly 20 percent in King County from 2013 to 2018. The report identified the resulting rent increases in LIHTC properties as a key factor in evictions.

Rental assistance also has the potential to help mitigate the growing threat of expiring affordability restrictions among LIHTC properties. LIHTC properties placed in service since 1990 have a minimum 30-year affordability period under federal law, with some state tax credit allocating agencies incentivizing or requiring affordability beyond the federal minimum. Accounting for states with mandatory affordability periods longer than 30 years, more than 387,000 LIHTC units in nearly 6,900 properties will reach the end of their federally mandated period of affordability over the next 10 years, and have no other federal project-based subsidies carrying affordability restrictions. Voucher holders in these properties, however, will still have their primary source of subsidy regardless of whether these properties are preserved.

Not all units reaching the end of their 30-year affordability period will be lost from the affordable stock. Some properties will receive further allocations of credits, extending affordability requirements. Other units might lose their affordability restrictions but remain relatively affordable in the private market. These units, however, would no longer carry income-eligibility and affordability restrictions. Even small rent increases for these units could lead to housing instability for the lowest-income LIHTC tenants without rental assistance. A smaller subset of units, particularly those with for-profit owners located in tighter housing markets, could reposition as much higher-cost housing, or convert to another use after restrictions expire. Access to rental assistance, particularly portable rental assistance like HCVs, could protect tenants when affordability restrictions are lost by allowing them to afford their current unit or another one in the private market.

Rental assistance can also improve the financial viability and physical quality of LIHTC properties. LIHTC properties, especially in weaker markets or those serving the lowest-income tenants, can struggle to meet operating expenses and build adequate reserves without ongoing operating support. Limited rental income makes it difficult to meet ongoing expenses such as maintenance or to build adequate reserves for future long-term capital improvements like a roof replacement, HVAC system upgrade, or renovations. A recent study of LIHTC properties in Detroit found the median project had only 41 percent of necessary reserves, and because of that, at least 5 percent of low-income units in multifamily projects were uninhabitable after 15 years of service. Rental assistance, such as HCVs, can stabilize or improve rental income and help build reserves. HCVs used in LIHTC units, for example, can provide higher payment standards than LIHTC rents. A 2014 report by NLIHC found that tenants with rental assistance can improve the rent revenue for LIHTC owners. In weaker markets where LIHTC rents can be similar to market-rate rents, voucher holders can be a stable source of tenants and help keep vacancies low in a property. Without rental assistance, it’s often difficult for owners to collect the maximum rents allowed. With it, owners can collect the full voucher payment standard even if it exceeds the LIHTC maximum rent set for a given unit. The additional income provided by rental assistance can be used to bolster operating income, or even cross-subsidize other units for extremely low-income renters who do not have rental assistance.

More capital subsidies are needed to address the mounting preservation threats and reinvestment needs facing the LIHTC stock. However, there is also an immediate need for rental assistance if the ultimate objective is tenants’ housing security and well-being. Rental assistance provides affordability and housing stability for the lowest-income renters within our nation’s largest affordable housing program, can contribute to the long-term financial health and physical quality of LIHTC properties, and can provide renters with a means to afford housing in the private market when preservation efforts fail. Not only that, but universal access to rental assistance could also support tenants in properties financed through other production programs like the national Housing Trust Fund, provide relief to renters struggling in the private market, and help renters afford housing after disasters. A significant and sustained investment in rental assistance is a commitment we must make.

I’m recently got evicted out of my home on July 20 from lakedallas because the people want to sell their home ,I had been there 14 years their and I raised my kids their ,I had just started work at the time I got evicted so I was under so much stress at the time I lost my job,because I just started so they let me go and now I’m homeless on the street bagging for a place to live all over again, I’m 50 years old and I’m about to be 51 on Aug 26,I had no home and no job and can’t get an one to help me out I’m scared, I need a place to live and I’m in good spirits about getting a job by need week, but I need some type of assistance, or voucher, I want to give up but can’t never been homeless before, can yall help me in getting a rental voucher ,my number is 940 735 5717,thank u again, please respond soon