[Update: 4/10/20: In the five hours after this story was posted, Bettie Salles received a flood of phone calls from readers, including staff at the mayor’s office. By 5:30 p.m. on Thursday, April 9, Parker was given a new key to his apartment, and slept at home that night. He told the author he was deeply grateful for the outpouring of support.]

In late March, just as New Orleans became one of the epicenters of the nation’s fight against the novel coronavirus, sanitation worker Bobby Parker, 56, found himself locked out of his apartment for paying his rent four days late.

As Parker walked away from his locked apartment, top New Orleans officials were begging people to stay in their homes, to help fight the pandemic. Earlier that month, the city’s Civil District Court judges had halted all residential evictions starting on March 13, a suspension that will be in place until at least April 30. And last week, after a legal-aid lawyer from Southeastern Louisiana Legal Services filed a petition on Parker’s behalf, the court’s on-duty judge ruled that Parker’s eviction had been unlawful and ordered Parker’s landlady to change the locks back to fit his key.

But Parker’s landlady, 92-year-old Bettie Salles, has refused to comply. She hung up the phone when asked about the matter, then sent a text saying: “REPORT THIS: pay the $2,395 due in cash today.”

It’s unclear how Salles reached that amount, since Parker’s monthly rent is $446 and no one is contending that he has missed any prior rent payments.

Though it’s cold comfort, Parker is not alone. While some property owners are working with tenants who can’t pay rent, says Hannah Adams of Southeastern Louisiana Legal Services’s housing unit, other landlords are “threatening eviction and using other tactics to bully tenants.” Some have refused to make necessary repairs or forced tenants to sign notes promising that they will pay all rent due once the pandemic has eased.

Frank Southall, lead organizer for the Jane Place Neighborhood Sustainability Initiative, said he’s heard much more about threatened evictions since March 31, as the first mid-pandemic rent payment is due for many tenants. “These are now becoming so common,” says Southall. “The landlord tells someone they have to leave, either because they don’t know the law, or don’t care, or are deliberately being deceitful to their tenants.”

Locked out in a pandemic

As hospitals in New Orleans have become overrun by COVID-19 patients, Mayor LaToya Cantrell ordered people to socially distance themselves and stay inside their homes. Instead, Parker, who is at high risk of serious illness because of a weakened immune system, has spent the past two weeks on friends’ couches or on a pile of blankets on their floors.

Sometimes, he ends up rolling up in his blankets and sleeping outside.

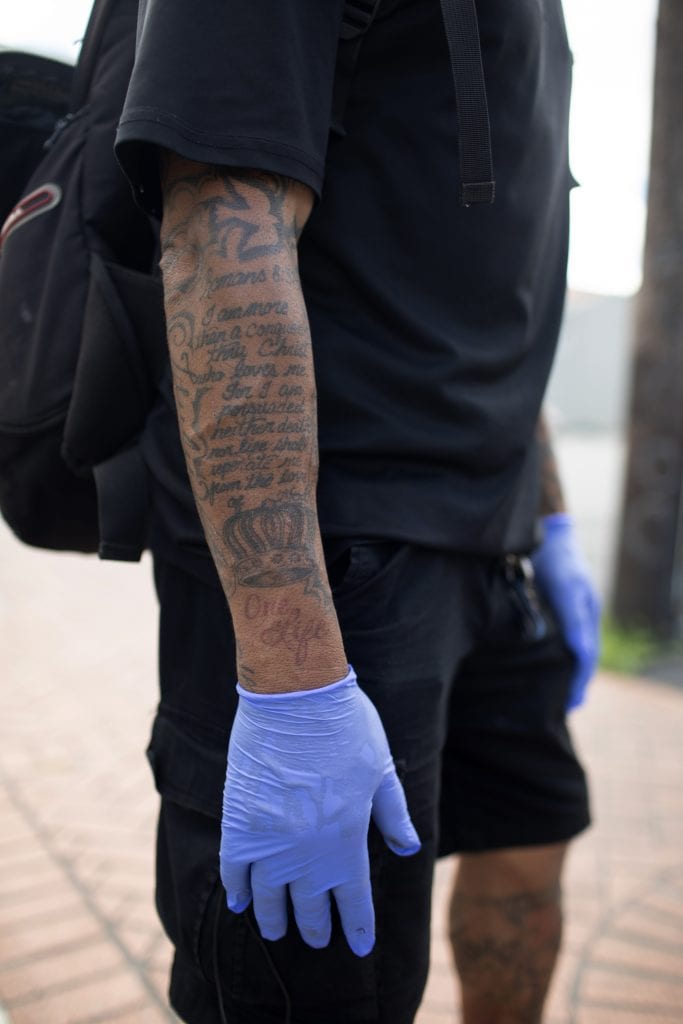

Before dawn, he gets up to catch the bus to his sanitation job in the French Quarter. He checks in, grabs a rolling trashcan, and begins to walk the Quarter’s narrow streets, picking up rubbish.

Though the city of New Orleans shut down Bourbon Street and issued a stay-at-home order in the face of spiking infection rates, Parker’s sanitation crew has stayed on the job, cleaning up after people buying groceries and pickup orders from Quarter businesses. So, if Parker could only get back into his apartment, he would still be able to pay rent, unlike many tenants across this service-industry town. “As of right now, I am still working,” he says.

Until recently, once Parker was done with work, he would head home, wash off the dirt of the day in the tub, and settle down for the night in the apartment where he lived for the past seven months.

On March 25, he made a cup of coffee and left his apartment at around 6 a.m. to go to work as usual. But when he got home at around 6:30 p.m., “When I put the key in the door, it didn’t do nothing,” he says. “I tried the top lock, then the bottom lock. I went to the back door. I couldn’t get in anywhere.”

coming home

Parker grew up in the city’s 7th Ward, on North Broad Street. His parents, Irving and Gloria Parker, were well known in downtown New Orleans because of their lavish annual display of light-up Christmas decorations. Each year, inflatable reindeer and Santa Clauses packed the front yard to the point where a steady string of cars pulled over at night, filled with families taking their children to see the winter wonderland.

After Hurricane Katrina, Mrs. Parker even found a massive inflatable FEMA trailer with Santa peeking out of the door. Bobby Parker wasn’t in town for those years; he had evacuated to Houston, where he was staying with his daughter. Then last year, he tired of living in a place that simply wasn’t home. “You can’t keep me from here,” he says.

Since Katrina, his daughter had been concerned that he wouldn’t get proper care because the storm left the city’s health care system in tatters. But last fall, he concluded that his city could now care for him. As the tattoo on his leg says: “New Orleans—still strong.”

In September 2019, Parker rented the back apartment of a nondescript single-shotgun house, one of two homes standing on a gritty, commercial block of North Galvez Street. The two houses are dwarfed by the block’s other buildings: a mattress warehouse, car wash, gas station, a longtime lock-and-key shop, and the bright-yellow Galvez Food Store, whose front façade is a wall of iron grates.

In the yearly lease, he agreed to pay $446 by the 9th of each month, a rent calculated through a formula set by the Road Home Small Rental Program, which mandated rents that are affordable to tenants earning below 80 percent of area median income for a set period of time, typically 10 or 20 years, in exchange for grants to repair their properties from the floods of 2005, after Hurricane Katrina.

If Salles has a federally backed mortgage of any kind, she would also be prevented from carrying out any evictions until July 25, due to provisions of the CARES Act. It can be difficult, however, for tenants to determine what kind of mortgage their landlords hold, which is why groups like the National Housing Law Project are arguing that the burden of proof should be on landlords trying to evict to prove in court they are not subject to this provision. [Editor’s Note: On April 17, the National Low Income Housing Coalition also released a searchable database to help renters in this position.]

The narrow white shotgun house had long belonged to the Salles family. Bettie Salles’s husband, Charles Salles, gave the North Galvez Street address as his home address in 1938 when he failed to stop for a stop sign, a violation written up in the daily newspaper. But by the early 1960s, the house had been turned into a rooming house that advertised “independent rooms for men.” A decade later, after a renovation, its apartments were advertised as three-room apartment—“bedroom/kitchen/bath,” renting monthly for $76 for couples, or $69 for a single adult.

The Salleses moved to a rambler in a New Orleans suburb. The two were active members of the North Wilshire Heights Garden Club, winning many awards for their landscaping while a daughter founded the Mercedes Benz Club of America. Bettie Salles became a busy real estate agent, advertising many properties in the newspaper from her Century 1 office.

from the flu to homelessness

On March 13, Parker was four days late paying rent to Salles. He’d fallen ill, tested positive for the ordinary winter flu, and missed two weeks of work. His doctors—worried that he might have pneumonia—asked him to spend a few extra days recuperating inside before he went back to work in the crowds of the French Quarter.

Parker said that he spoke to his landlady on March 9 and told her he would be a little late with the rent because of his health problems. On March 13, when Parker was ready to pay his $446 rent in full, he knocked on the door of the house’s front apartment. There, he talked with his neighbor Jamie Carter, who collects Parker’s rent for Salles each month.

Carter contends that Parker only had $400 that day, not the full $446. But Bettie Salles wouldn’t have accepted $446, Carter and Parker says. According to Salles’ calculations, Parker owed an additional $400—or $100 per day in late fees. Parker couldn’t afford that.

Late fees are permissible, says Eric Dunn, director of litigation at the National Housing Law Project. “But they have to be reasonable. I guess if you were renting the Taj Mahal, $100 [per day] might be reasonable. If not, I don’t think that those fees would be enforceable.”

Faced with the late fees, Parker pleaded with Salles. “You’re going to get your money,” Parker says he told her on the 13th. “That is not a problem. But look what’s going on in the world. Do you have a heart?”

He could not persuade her to waive the fees, and in fact, she added in a portion of her water bill as well. “If you don’t have my $911, get your butt out,” she told him, he says.

After discovering he was locked out on Wednesday, March 25, Parker’s first call was to Noelle Deltufo, his medical caseworker, who connected him with Andy Maberry, a lawyer at Southeastern Louisiana Legal Services. Deltufo also got on the phone and told Salles that her organization, the federally qualified health center CrescentCare, could send her a check for $446, to be sure that Parker could stay housed and healthy. After talking with Deltufo and Maberry on March 25 and 26, Parker had high hopes that he could be back home in a few days. After all, Deltufo had requested that a check be sent to his landlady. And Maberry had told him that, even during normal times, tenants with a valid lease can only be evicted after a hearing before a judge. Currently, even those evictions were suspended.

Yet Salles had simply locked him out, using a do-it-yourself eviction method that isn’t legal even if the city weren’t in the midst of a pandemic.

a little shaming goes a long way

The Jane Place Neighborhood Sustainability Initiative had already identified rampant evictions as a major problem in the city. Last year, Jane Place published a careful analysis that found that the annual, court-ordered eviction rate in New Orleans stood at 5.2 percent, nearly twice as high as the national rate.

Since the pandemic struck, Jane Place and other local housing advocacy groups have held weekly virtual meetings to discuss current housing threats and determine possible long-term economic policies to help those affected. They are also trying to support tenants facing illegal evictions, through legal referrals and basic information: “We explain to people that they don’t have to go anywhere,” says Southall, Jane Place’s lead organizer.

“The biggest challenge comes when we hear of lockouts,” Southall said. “If landlords don’t respond to an order from a court of law, we go to the court of public opinion: We get the word out and point out publicly which landlords are acting like cowards in the middle of a pandemic.”

So far, the targeted public shaming has taken the form of phone calls to local leaders, and has proven effective, Southall said. In several cases, “after members of our community contacted councilmembers, the mayor, and local officials, landlords relented.”

To date, no one has taken any public action against Salles, Southall said.

a legal win, but still on the street

Sometimes, wrongful-eviction cases can be resolved with a simple conversation. So on Friday, March 27, Maberry called Salles directly. “Bobby Parker has every right to be in there,” he says he told her, explaining that evictions had been suspended within the city.

Salles told Maberry she’d have the locks changed back by 4:30 p.m. that day.

That afternoon, after 4:30 p.m., Parker went back to his apartment and tried his key in the lock. No luck.

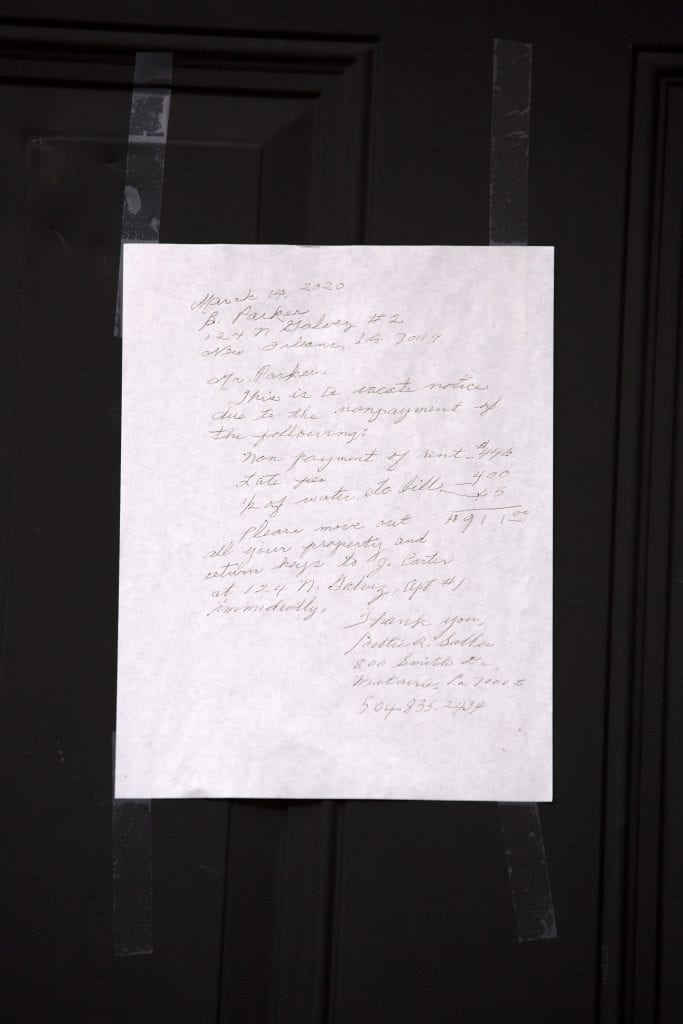

He stopped for a minute to scan a handwritten note, backdated to March 14, that Salles had posted on Parker’s door. “This is a vacate notice due to nonpayment of the following,” she wrote in tidy cursive. “Non-payment of rent: $446; Late fees: $400; ½ of water, etc. bill: $65.” The total was marked as $911.

Carter came outside onto their shared back porch and put Salles on speakerphone as Parker asked if he could get into his apartment to grab a spare work uniform and a few bottles of prescription pills.

“I need my medicine,” Parker says.

“Don’t open the door,” Salles instructed Carter, still over speakerphone. “He can go to the hospital to get more medicine.”

Carter said that Salles was determined not to let him back into his apartment because she resented the legal intrusion. “The reason Ms. Bettie don’t want to give Bobby his medicine is because he went to the lawyers and told the lawyers that he doesn’t just want his belongings from the house, he wants to move back in,” Carter says. “She was going to let him get his belongings from the house, but he went to the lawyers.”

Parker tried to no avail to explain that Salles had flouted basic landlord-tenant law.

A few days later, Parker’s claims were successful in court. On March 31, Judge E. “Teena” Anderson-Trahan of Second City Court ordered Bettie Salles to change the locks back, because Parker had not been afforded “judicial process.”

As of Thursday, April 9, Salles had not heeded the judge’s order.

There’s little that Maberry can do now. “Because a hearing wouldn’t be able to take place until at least May, it really wouldn’t do anything in terms of forcing Mrs. Salles to physically change the locks,” Maberry says.

Still, despite the delays, Maberry’s main objective hasn’t changed. “The No. 1 goal is getting him inside. This means Bobby needs to take whatever measure necessary to get back in,” Maberry says.

On a recent day, Parker bent over and picked up some litter on North Rampart Street and talked about where he’d slept the night before: outside, under his blankets. He had been so optimistic at first, he says, because he felt like the law was on his side. But now, a week had passed and nothing has changed. “I still believe that we can win this,” he said. “But I’m feeling a little discouraged.”

You need to get your facts straight . That property mentioned is owned by the individual mentioned but in no way was the property management of that rental property managed by my company Century 21 Action Realty in any way. Ms Salles managed her rental property entirely on her own. Furthermore, the fact that Ms Salles managed her own personal rental property has absolutely nothing to do with my company as we did not represent Ms Salles property management on that property. Since you posted this article my office has been bombarded by harassing hate calls making vulgar threatening remarks to my only employee my secretary and posting on social media encouraging folks to not use our company. I take offense to this reckless reporting without even so much as getting my input before posting a news article implying my company had anything to do with the alleged incident. Your article is now causing much slander damage towards my company which no business person should be forced to endure by any media outlet. You owe me an apology and a follow up article making it clear to your readers my company had nothing to do with that alleged incident. Ms Salles acted totally on her own on this issue.

Has your company been using tactics mentioned in the article, such as lockouts or having tenants sign agreements that state rent will be paid after the pandemic? Perhaps you were getting threatening calls because you’ve already been using tactics to evict people from their homes during a pandemic. Shame on you!

Maybe your business should publicly denounce Mrs. Salles’ illegal and immoral behavior as a way to distance yourself. Or are you supportive of her behavior?

What a horrible person. I hope she is no longer employed by Century 21. If she is, they need to do the right thing and distance them from her. I know if my Agent did something like this, I wouldn’t allow her to rent out ANY of my properties, immediately. Such a sad situation, what a sad lady.

Katy Reckdahl, If what Tim McCubbin (commenter above) is correct and that as he is saying, Ms. Salles was not an agent affiliated and having a license posted with this Century 21 agency, then he is CORRECT. You should be issuing a retraction of that part of your story. Given that Ms. Salles is 92 years old by your own report, I highly doubt she is an active agent anymore. Most “journalists” would have keyed into that and looked a little further.

I firmly believe the media is trying to destroy this country through one sensational hate inducing story at a time. It’s not partisan either, and happens across lines equally. Every headline is written with a bias to evoke anger in a certain group, headlines and polarizing are more important than fact checking. It’s really quite disgusting and I can’t imagine how anyone with a moral compass can go into journalism.

Yes, you CAN wreck people’s lives and cause damage by irresponsible reporting. Do the right thing and retract your association with Century 21 in this story.

Yes, she is 92, but she is still a practicing agent. I’m not sure if she is still with Century 21, but she is still working!

I can attest that she is 92, bent over, can barely walk but is still an active agent. AND that she is a mean nasty old lady to deal with. She combs the for sale by owner ads offering her services as a low commission full real estate agent service. But the fine print is that she offers her services for 3% and asks for a 1 YEAR term. 2% for herself (and Century 21) and ONLY 1% for the buyers’ agent. The problem with that, is NO other agents will bring their clients to your home for a 1% commission and if they accidentally do, they will discourage their buyers from buying your home for only a 1% commission. She does all initial work over the phone, so you do not see that she is actually incapable of climbing stairs and showing a 2 story home. On top of that, after NO action, if you try to get out of her contract she gets very nasty like she did with her tenant.

As far as Century 21 is concerned, they have enabled her to be a crappy agent for years. Her manager has received multiple complaints about her, but did nothing to stop her shady practices.

Bettie Salles is a crap human. I hope she gets the flu, and just as she recovers, is made homeless for a week or two, having to couch surf and sleep outside some nights. I also hope her tenants bail on her when they get a chance. To be 92 and that hateful and greedy is astounding. She deserves whatever backlash comes her way.

THIS ENTIRE LIBELOUS AND SLANDEROUS ARTICLE IS FAKE NEWS, AND TRASH IS 100 PERCENT UNTRUE—–HE ABANDONED HIS LEASE —-WALKED OUT AND REFUSED TO TAKE ANY CALLLS SAID HE WAS MOVING IN WITH HIS DADDY, LEFT A LOT OF ROTTING FOOD AND CIGARRETTE BUTTS, HE WAS AN ALCOHOLIC AND A DRUG ADDICT WHO WAS NEVER TRUSTWORTHY AND NEVER SOBER. —–THIS TENANT ABANDONED HIS LEASE, NEVER EVEN PAID HIS DEPOSIT, LEFT THE APARTMENT FULL OF FILTH AND DAMAGED THE DOORS AND THE OVEN AND STOVE—-NOW THAT IS THE WHOLE TRUTH.

YOU HAVE NO CLUE OF THE FACTS—-THIS TENATE ABANDONED HIS LEASE, TRASHED THE APARTMENT, AID HE WAS MOVING IN WITH HIS DADDY—-AND NEVER EVEN PAID A DAMAGE DEPOSIT——SO SLANDER AND VICIOUS IGNORANCE OF THE FACTS IS THE ISSUE HERE AND AND A PUBLIC RERTRACTIUON AND APOLOGY TO THE FINEST REAL ESTATE AGENT IN THE WORLD IS OWED TO MISS BETTIE RENA SALLES.