Poverty is typically defined and measured in purely economic terms, such as income at a specific point in time. As a field, community development aims to reduce poverty through various approaches that expand economic opportunity for low-income people. However, as the United Nations makes clear in its report “Rethinking Poverty,” an emphasis on the monetary and economic aspects of poverty often overlooks the human experience of what underlies it: social exclusion and social vulnerability, which are the result of the systematic denial of opportunities and choice. As humans, we are hardwired with a fundamental need to belong, evidenced by the fact that our brains respond to social exclusion in a similar manner to physical pain. It should not surprise us then that poverty, and in particular the repeated experience of social exclusion and vulnerability that too often accompanies intergenerational poverty, would have serious implications for people’s mental, emotional, and behavioral health.

The most recent issue of the Community Development Innovation Review explores the intersection of community development and mental health from various angles, such as the affirming value of residents taking action in their communities, the role of arts and culture addressing stigma and shame, or the rationale for bringing a trauma-informed lens into affordable housing. Throughout the issue, a recurring theme is the acknowledgment that low-income neighborhoods, and in particular neighborhoods with high concentrations of people of color, have been consistently excluded from an economic system that too often confers benefits to some at the expense of others.

Redlining as a Form of Systemic Exclusion

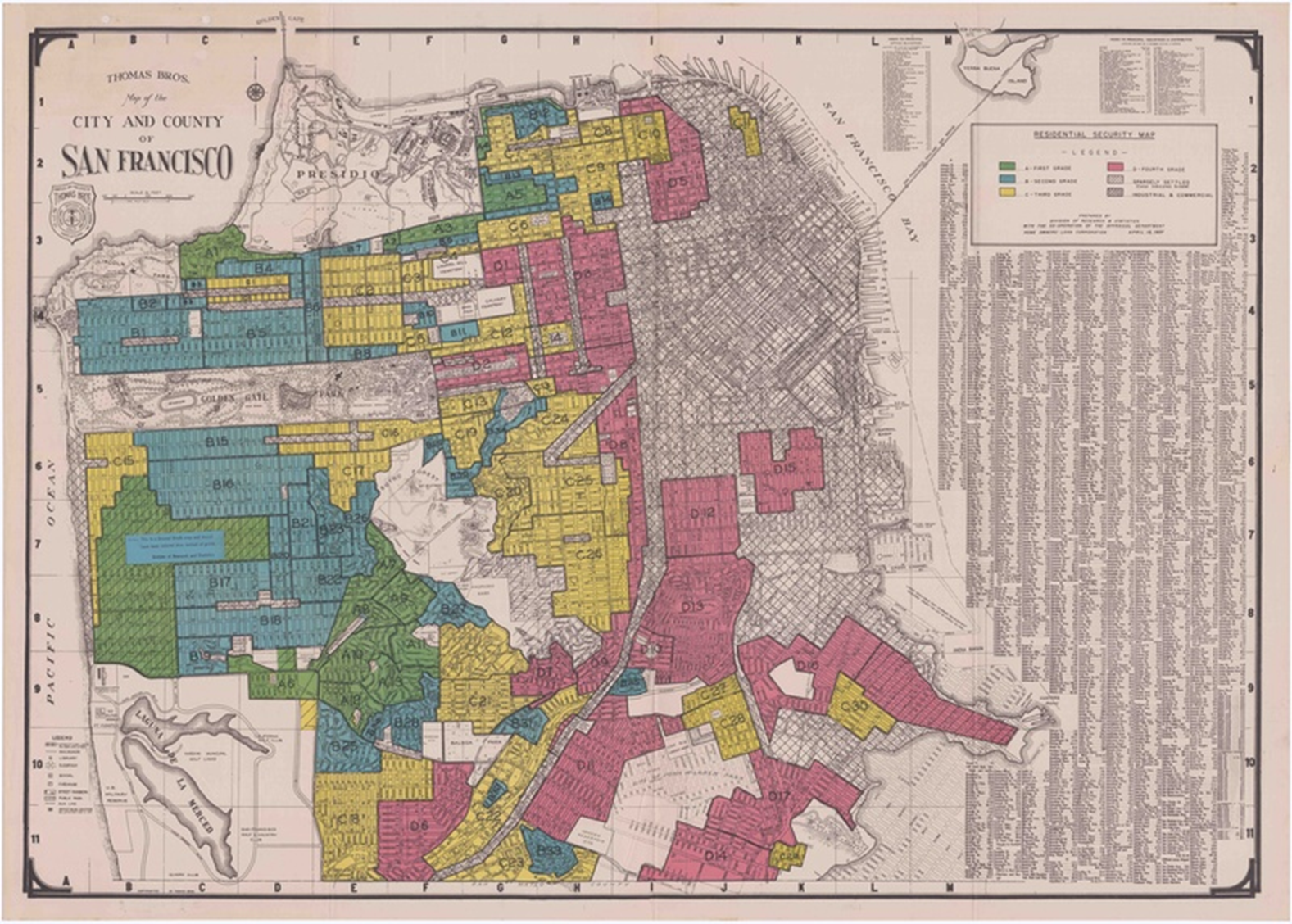

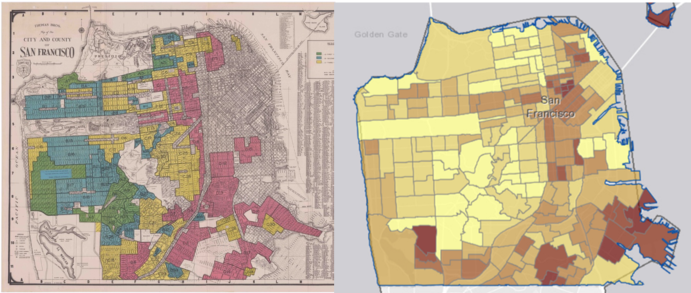

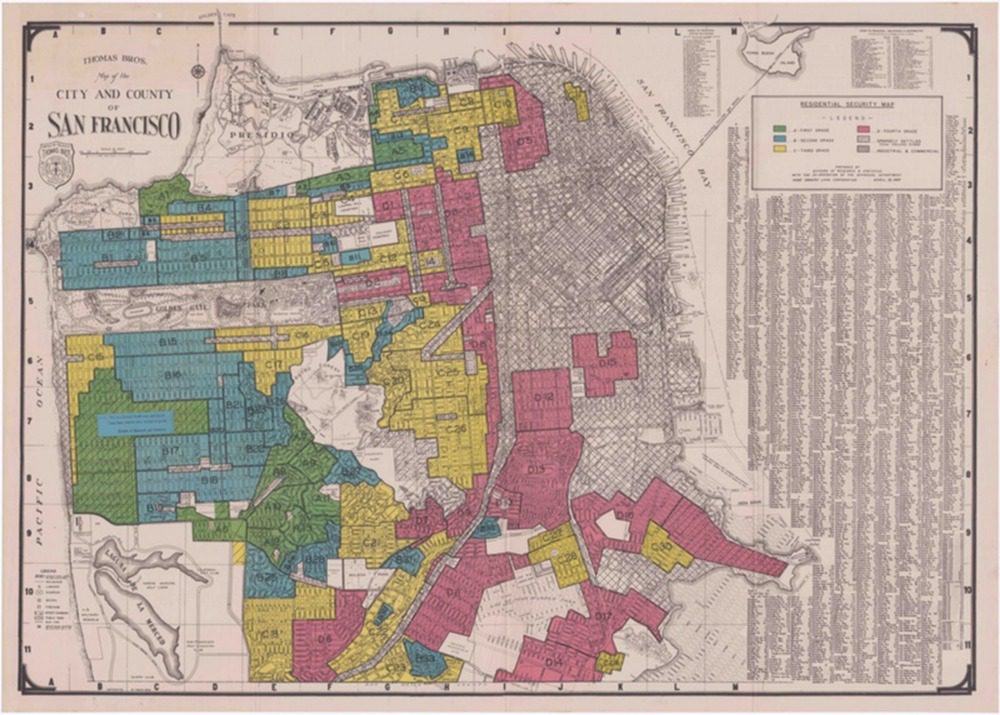

One of the prime examples of the systematic denial of opportunities and choice is the practice of redlining, which dates back to the 1930s, when the federally created Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) developed color-coded maps to indicate the relative risk of different neighborhoods. Areas deemed high risk were marked in red, which provided the justification for the Federal Housing Administration to deny mortgage credit access to borrowers in these neighborhoods. A HOLC map for San Francisco (Fig. 1) shows that neighborhoods like the Fillmore, Potrero Hill, Bayview, and Hunters Point were redlined.

Figure 1. HOLC Map for San Francisco. Source: Mapping Inequality.

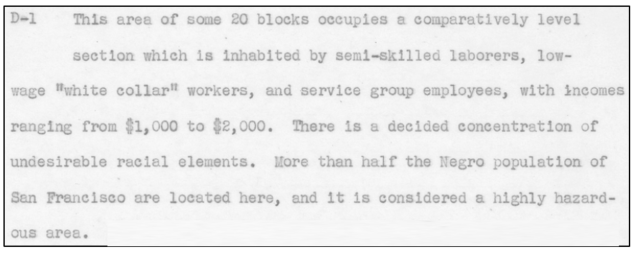

When we examine the detailed neighborhood descriptions that provided the rationale for the color coding of each map, it becomes clear that redlining was an explicitly racially motivated practice of exclusion and denial of opportunity. For example, consider the description for San Francisco map area D-1, just west of the Fillmore (Fig. 2), which states, “There is a decided concentration of undesirable racial elements. More than half the Negro population of San Francisco are located here, and it is considered a highly hazardous area.”

Figure 2. HOLC Area Description for the Fillmore. Source: Mapping Inequality

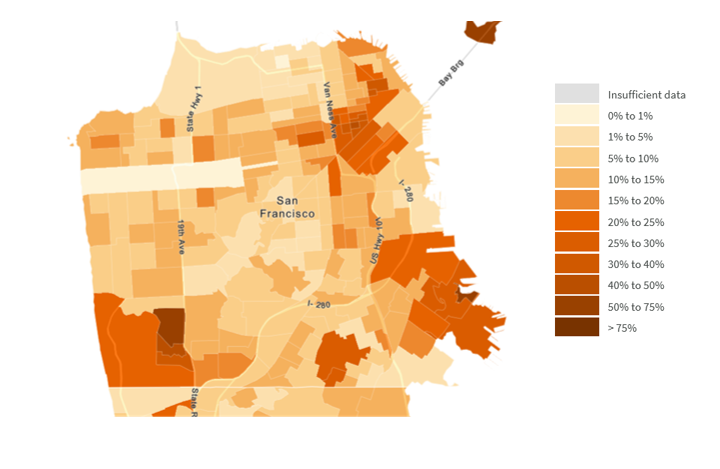

The systematic exclusion of entire neighborhoods from mortgage credit access during the postwar period has had major implications for the economic disparities we see across neighborhoods today. As Fig. 3 shows, many of the same communities that were redlined 80 years ago still experience higher concentrations of poverty in the present.

Figure 3. Share of adults in poverty, San Francisco 2016. Source: 2016 ACS 5-year estimates, via Social Explorer

Poverty, Place, and Mental Health

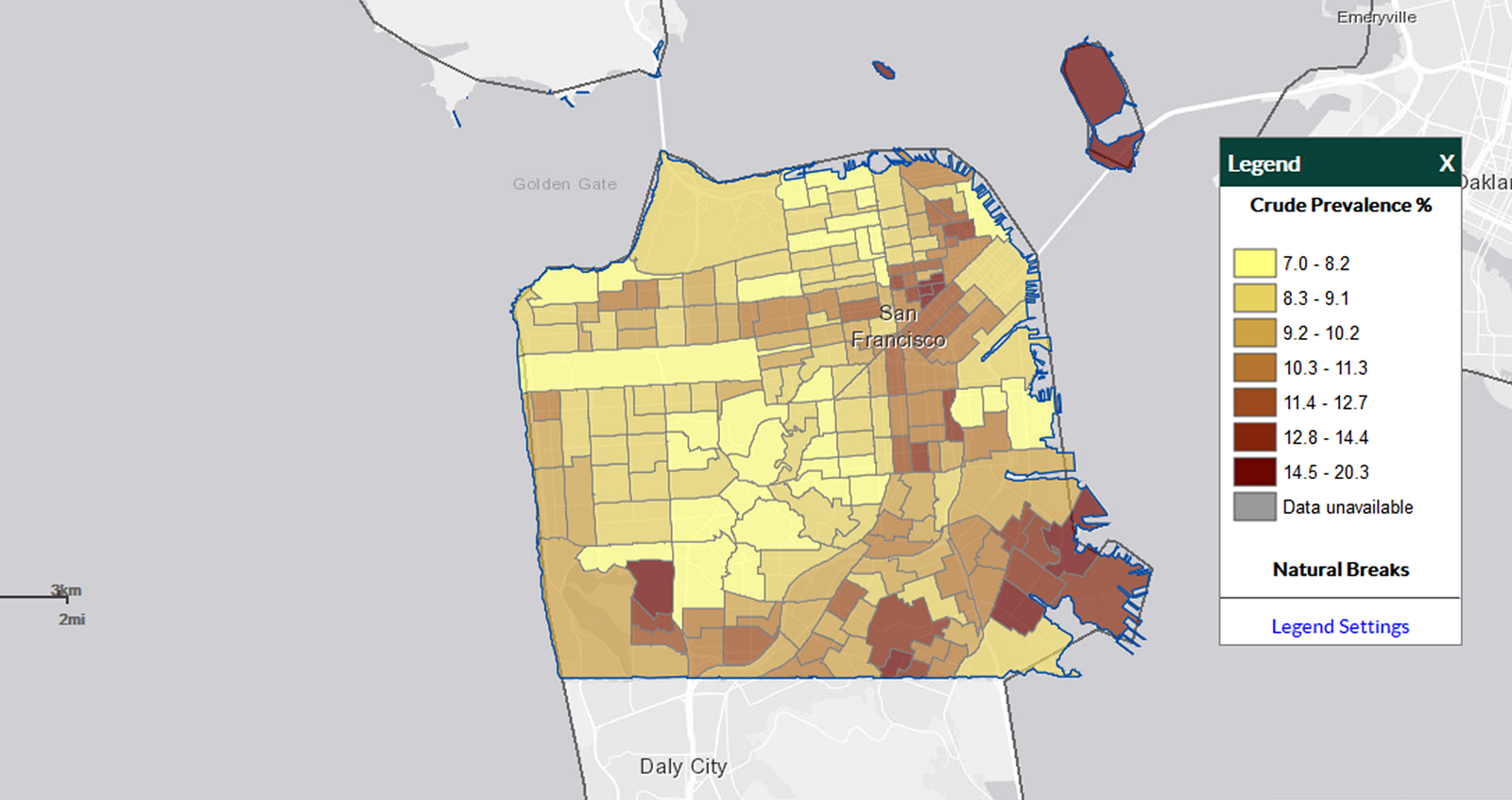

As the past decade of healthy communities efforts across the country has shown, poverty is also highly correlated with poor physical health outcomes, particularly preventable chronic diseases such as diabetes, heart disease, and asthma. There is also a correlation between poverty and poor mental health, as demonstrated in Fig. 4, which shows the prevalence of adults who report that their mental health was not good for 14 or more days out of the past 30 days. Poverty is a major risk factor for poor mental health, as it increases the likelihood of negative factors such as adverse childhood experiences, social isolation and loneliness, discrimination, and detachment from academic or work achievement. These negative experiences can diminish a person’s sense of control, self-efficacy, connectedness, and hope, all of which are important elements for resilience and mental health promotion. People in poverty are also less likely to have protective factors that promote mental health, including many of the things that community development works to provide, such as stable housing, supportive community networks, and financial security.

Figure 4. Poor mental health prevalence among adults, 2016. Source: 500 Cities project (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation)

A side by side comparison of the maps (Fig. 5) reveals a strong spatial relationship between a history of systemic exclusion in the form of redlining and poor mental health, with persistent poverty serving as the through line that connects these issues across generations. Although the causal pathways are complex and multifactoral, it is clear that neighborhood level factors, and therefore community development interventions, do indeed matter for mental health.

Figure 5. Side by side comparisons of redlining and poor mental health prevalence in San Francisco

Looking to the Future

The World Health Organization defines mental health as a state of well-being in which every individual:

· realizes his or her own potential;

· can cope with the normal stresses of life;

· can work productively and fruitfully; and

· is able to make a contribution to her or his community.

Notably, mental health is not defined as the absence of mental illness, nor is it equated with mental illness (an important distinction, as people often use the terms interchangeably). Rather, mental health is framed as a positive state of well-being that is directly tied to the economic and social outcomes that community development strives to achieve.

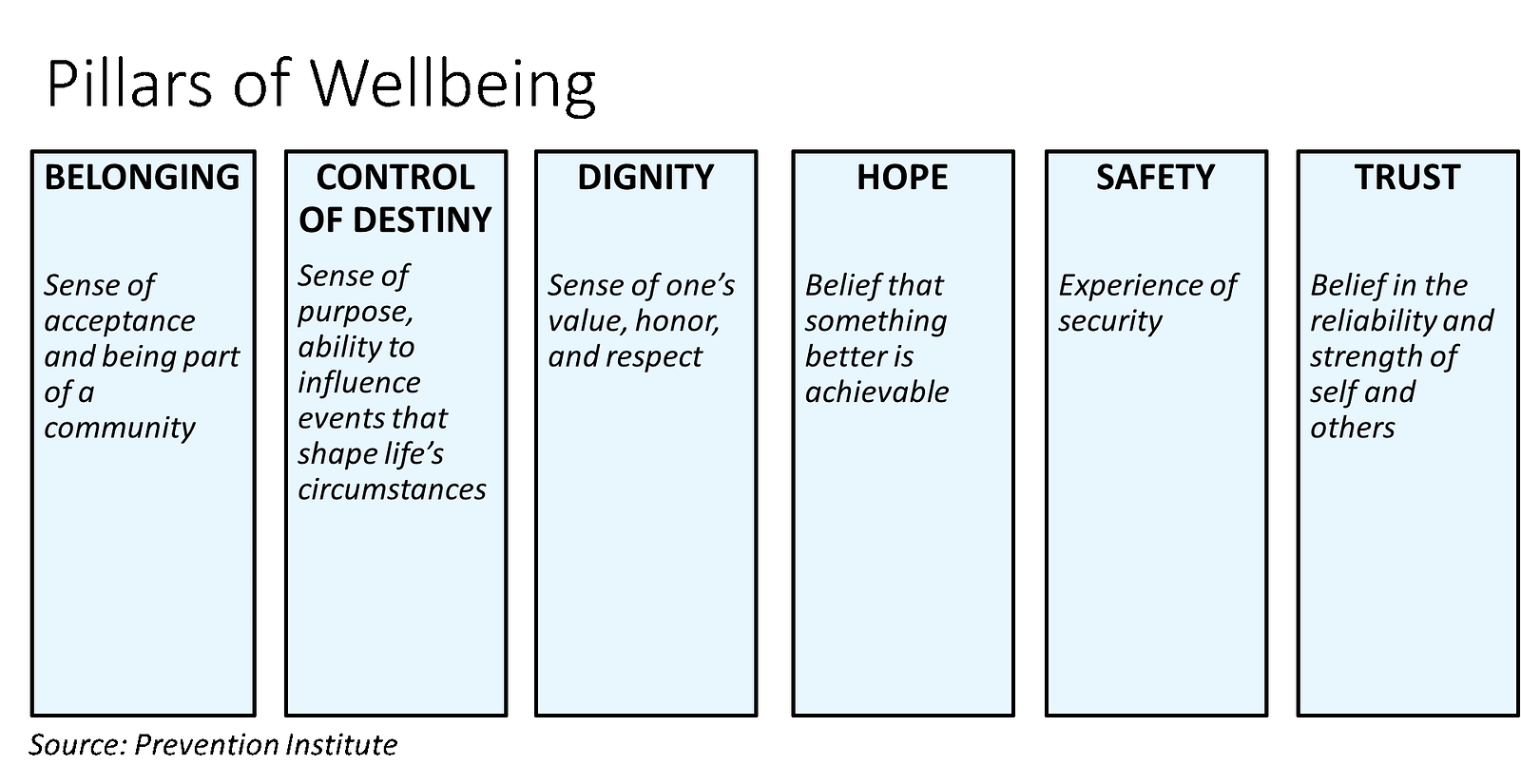

As we look to the future, the field has the opportunity to deepen our understanding of how community development efforts can be designed to strengthen the mental health and well-being of the populations it serves. The Prevention Institute’s “Pillars of Well-being” (Fig. 6) provides a helpful conceptual framework for understanding the key elements needed for people and communities to thrive. These pillars of well-being, such as belonging, dignity, and hope, are absolutely central to achieving the goals of community development and must be lifted up with greater intention. They also bind us together in our shared humanity and can serve as a unifying vision across sectors. As we look to make changes across our systems, we can ask ourselves—how do our policies and the design of our communities uphold these pillars?

As Tyler Norris, chief executive of Well Being Trust, says, community development is about creating the vital conditions for intergenerational well-being. Let us never lose sight of the injustices of the past, but may we also never lose hope for a just and better future.

This article originally appeared on the official Medium channel of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

The views are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or the Federal Reserve System.

WHat a moving and insightful article. I thank you for writing it and doing the work related to the issues. I am a schizophrenic artist who is working on an exhibition including visual art, performance, and writing. It has a huge installation and is done on the streets or parking lot near skid row in Los Andeles. I am very interested in what you are writing about. please keep me informed of future writings.