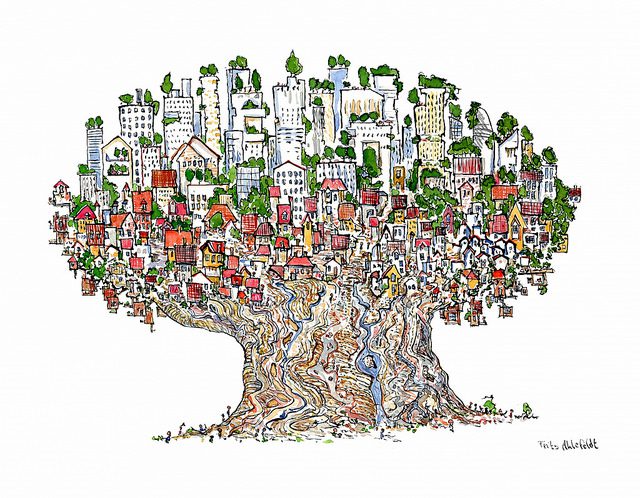

Tree City Architecture. Illustration by Fritz Ahlefeldt via flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

In the last year, displacement has become a hot topic for policy analysis and intervention in New York City and across the country. For example, in 2017 the Regional Plan Association released its fourth plan for the NY-NJ-CT region since 1929, and it included a report titled Pushed Out: Housing Displacement in an Unaffordable Region.

Vicki Been, former commissioner of NYC’s department of Housing Preservation and Development and now professor of public policy at the NYU Wagner Graduate School of Public Service and faculty director of NYU’s Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy, released a paper “What More Do We Need to Know About How to Prevent and Mitigate Displacement of Low- and Moderate-Income Households from Gentrifying Neighborhoods.” Public officials and staff from 10 U.S. cities (Austin, Buffalo, New York, Denver, Nashville, Philadelphia, Portland, Oregon, San José, California, Santa Fe, New Mexico, and the twin cities of Minneapolis and Saint Paul) joined together with PolicyLink to form The All-In Cities Anti-Displacement Policy Network. The Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development (ANHD) and the Pratt Center for Community Development released The Anti-Displacement Toolkit to Fight Displacement in NYC Neighborhoods and Flawed Findings: How NYC’s Approach to Measuring Displacement Risk Fails Communities, respectively.

Together and independently, these initiatives acknowledge displacement as a critical policy issue related to housing and urban development and aim to create and share resources for those doing planning and housing work in cities across the country.

Underpinning these initiatives are certain assumptions about what displacement is and why it matters. Commonly, these reports focus on residential displacement, and discuss it at the individual-household level. They discuss how forced or coerced moves from one’s current housing may affect their health, employment, neighborhood and housing quality, and finances. In addition, anti-displacement policy is discussed vaguely in the vein of social justice. If race and ethnicity are specifically mentioned, it is from a justice perspective; with the addition of clarifying that everyone, regardless of their background or circumstances, has a right to housing. All of this is underpinned by the notion that anti-displacement policy and action is about creating more prosperous and healthy communities and cities for all.

I am thankful that displacement is getting some serious attention from housing and community development professionals and policymakers, and I don’t disagree with the concerns highlighted in their work. But I also think the work overlooks an important perspective—that in contrast to the narrow, individual/household level analysis and redress, displacement is a place-based, community-level phenomenon, and that anti-displacement work is also about community preservation.

Placeing Displacement

As is evident in the term, dis-place-ment is about place and separation from it. At the individual level, we focus on the separation of a household from their dwelling. At the macro level, place means a neighborhood and its human community. Here, neighborhood is not just a geographically bound, socially labeled space, but a place characterized by local institutions, organizations, businesses, recreational and public spaces, and more; while community includes those who live and/or work in the neighborhood—renters, owners, and those in the shelters, streets, and parks. Together, neighborhoods and their communities can be understood as a set of dynamic yet stable relationships that ground community members, offering them a sense of rootedness, belonging, familiarity, and security, all of which help orient them to the world and to themselves (see for example, Jacobs, 1992; Fullilove, 2004; Tuan, 1977).

In addition to contributing to one’s sense of self, these neighborhood and community components are a series of intertwined networks of dependency and reciprocity through which resources are shared and secured (i.e, money, food, shelter, clothing, employment, social support, sense of belonging, safety, and security, etc.).

Navigating and securing resources through these networks may include things like:

- Gaining employment at a local business through a social connection to or relationship with the owner.

- Meeting with friends at a local park to debrief about the week, sharing exciting news, venting about work, relationships, or money.

- Participating in weekly religious services to connect with neighbors, and to support and help maintain an important local institution.

- Leaving unneeded belongings in front of your home so passing neighbors can take what they need.

- Passing on information to less experienced neighbors about the safest and best streets in the neighborhood to walk down after dark, and more.

Such resources are material, social, and relational in nature, and we secure them not through “markets” or with cash at the store, but through complex, place-based, familiar and familial relationships; and they are critical to our ability to survive and thrive in this world, offering us sustenance and nourishment for our mind, body, and soul.

The concept of diverse economies frames these resource-rich, life-sustaining networks as informal, alternative economic activity, and situates them alongside the formal economic activity of our capitalist society. According to J.K Gibson-Graham, these economic activities have been made invisible by the dominant understanding of our country and our economy as singularly “capitalist.” This has led many of us to narrowly conceive our economy and economic behavior as wage work, or traditionally recognized labor done in exchange for money. It is then assumed that this money will be leveraged to secure tangible, life-sustaining resources such as housing, food, clothing, and transportation.

But what happens when one has largely been excluded from formal capitalist markets, or when the amount of money one receives in exchange for formal labor market participation isn’t enough to cover one’s basic needs? Or when one is simply unable to obtain formal employment? Or when the cost of one basic need—housing, for example—takes up 30 percent, 50 percent, or more of one’s wages, leaving a household with fewer dollars to secure other necessary resources like food, transportation, school supplies, or child care? What do households do then?

Many households in this position make up the difference by participating in alternative economies, for example, a neighbor shares food with another neighbor, a retired neighbor offers low- (or no-) cost child care, a couple shares a bus or train pass and relies on neighbors to swipe them through the turnstile when scheduling conflicts arise, or the bodega owner offers credit or charges long-time neighbors lower prices than new residents living in the recently erected luxury towers on the corner.

On the surface, these can seem like simple niceties, but in some neighborhood communities, particularly working-class communities of color where housing segregation and ghettoization overlap with labor market segmentation and exclusion, these diverse economic networks have been and remain critical to the ability of community members to survive and thrive.

The historical and material significance of community networks to marginalized communities is nowhere more evident than in the deeply historical excavation by Dr. Jessica Gordon-Nembhard, professor at the City University of New York’s John Jay College, in which she lays out the cooperative networks and community ethos undergirding the mutual-aid societies and the cooperative economic and housing initiatives that have propped up the Black community long-standing.

Today, a household’s ability to secure resources through these informal networks or alternative economies isn’t guaranteed, and is directly threatened by the wave of displacement moving through cities. Displacement not only threatens households with the prospect of a forced move, but also by distancing households from networks that are critical to their survival.

Even for households that are not physically displaced from their neighborhood, the breaking up these networks—as other residents, small businesses, and local social institutions and organizations are forced to relocate or dissolve altogether—is equally threatening.

With respect to the evolving interest in displacement and anti-displacement policy, it is critical that we consider the threat and consequences of displacement from a community-centered perspective. Policy initiatives must acknowledge the ways in which communities are ecologies that work together to sustain households, and must devise solutions that maintain these social connections and networks and sense of community. Not doing so poses as much threat to households as physical displacement.

The formal way govt at all levels has putatively addressed this nexus between displacement & job insecurity is via their “economic development” regimen, which goes critically unexamined year in, year out. Given the tens of millions spent each fiscal year to spur “job creation” directly & primarily with the commercial real estate industry, policymakers have gotten a free pass, as they are allowed to abuse a system theoretically designed to address income inequalities & structural poverty. We do not need to reinvent the wheel.

This remains a critical missing link in this discussion. We don’t need a “new assessment”, we need greater transparency & accountability of adopted plans intended for “job creation”, but in areas where needs are greatest. We need to stop with a “new” analysis & policy prescriptions: investigate & examine what is already there before our eyes. This discussion only reveals how little we actually know, much less where we really need to be; enough with starting at the front-end of things rather than specializing at the back end, where results, impacts, & outcomes are revealed.

Let’s stop being excited about the sizzle rather than looking for the steak.