Geary Rivers in his Penn Plaza apartment before he moves to a smaller living space. Photo by Maranie R. Staab

From left, Crystal Jennings, Karen Edmonds, Alethea “Lee” Sims, O’Harold Hoots, and Mel Packer rally in front of LG Realty’s office in downtown Pittsburgh. Photo courtesy of Jason Vrabel

It’s January 2017 on the seventh floor of 5600 Penn Plaza in Pittsburgh, a red brick building with 154 apartment units. Mabel Duffy’s belongings are sealed away in cardboard boxes that were once used to ship fruit and liquor, piled high against the wall of her living room. In her bedroom, more boxes and black garbage bags full of clothes encircle a simple wood-frame bed. A smaller second bedroom is crowded with two single beds for her 20-year-old granddaughter and her boyfriend. Mabel’s home looks as if she’s a few days from moving out.

But she isn’t moving out, at least not yet. It’s been a year since Mabel, 78, was relocated from the building next door. That one was demolished, and this one will soon follow.

Most of Penn Plaza’s 200 evicted residents are gone. Some found new permanent housing while others are bouncing between temporary stays. The 20 who remain have until March 31 to vacate.

Black earmuffs hold down Mabel’s ash-white hair. Her sweatshirt, sweatpants, and white sneakers suggest she’s heading out for the day, but right now she sinks into her worn green armchair. “It’s even colder than usual in here today,” she says to Myrtle Stern, her friend and neighbor from down the hall. “Your place is warmer than mine!” Myrtle erupts with a hint of a smile. “Why you think I’m down here?”

“When I came here nine years ago, I thought I’d be able to die here,” Mabel says. “I don’t want to move again.” Under a small table lamp she sorts through new apartment listings made available that week by the building’s relocation office. “I can’t do this again.”

Penn Plaza is the property of LG Realty Advisors, a “diversified real estate company headquartered in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.” LG has managed the building in the East Liberty neighborhood for decades, but in the summer of 2015, it issued 90-day eviction notices to residents spread across the two-building complex. In response to public pressure, Mayor Bill Peduto’s office intervened, and in cooperation with a residents’ tenant council and community organizers, reached an agreement with LG.

The ensuing Memorandum of Understanding signed by all parties detailed a two-phase eviction process, one for March 31, 2016, and the other for the end of March 2017. Each tenant would receive between $800 to $1,600 in “move-out payment assistance” to cover U-Haul rentals, security deposits, and first month’s rent. LG would bear that cost, totaling approximately $250,000. The city’s Urban Redevelopment Authority paid a nonprofit, Neighborhood Allies, $300,000 to manage the two-year effort. Neighborhood Allies subcontracted the work to Interstate Acquisition Services (IAS).

‘They’re Trying to Freeze Us Out’

On the doors of vacant units in Mabel and Myrtle’s corridor is scribbled in black marker: APPS AND CARPET OUT (“Apps” meaning appliances). Every few days, another tenant is gone, another door written upon. For those who remain, these signs are another reminder that their doors will be written on soon, too.

Myrtle Stern and Mabel Duffy stand in a Penn Plaza hall whose windows are sealed with plastic sheeting and adhesive spray. Photo by Maranie R. Staab

Myrtle, 76, has unpacked more of her belongings since she, too, moved from the other building a year ago; her apartment is somewhat more settled, less in limbo than Mabel’s. Healthy potted plants are clustered around her kitchen window below a cracked ceiling that leaks on rainy days. Framed prints of her children are displayed throughout, including one of her son Darwyn in his Michigan state trooper uniform. Near the front door are several garbage bags of clothes.

“My great-granddaughters are leaving today,” Myrtle said of the bags. The girls have been living with her during their mother’s hospital stay for knee replacement surgery. They live about five blocks away.

Mabel and Myrtle have traveled a long road together for 12 years. Both previously lived in nearby Auburn Towers, a public housing complex owned by the city’s Housing Authority, where Myrtle served as president of the tenants’ association. As part of a future redevelopment project, it too was demolished.

On Jan. 20, Mabel and Myrtle wait in their coats for someone from the relocation office to take them to see an available apartment. On Myrtle’s dining room table is a digital thermometer that records both temperature and humidity next to a piece of paper with the daily indoor temperatures written in blue. “They’re trying to freeze us out,” she said of the building’s owners. Complaints of wildly fluctuating temperatures throughout the building led Helen Gerhardt, a founding member of Homes for All Pittsburgh, and a member of the Pittsburgh Commission on Human Relations, to purchase thermometers for the remaining residents. The Allegheny County Health Department requires that property owners maintain a minimum temperature of 68 degrees. Twice Myrtle’s thermometers recorded 63 degrees, which the Allegheny County Health Department considers a “major health hazard.”

In just the past week, the women have traveled by car or bus to several apartments where the landlord stood them up, or arrived to find that units were on the top floor of three-story walkups.

Today, their ride never shows up.

Pittsburgh: ‘A Hemorrhaging Patient on the Operating Table’

Across a spectrum of American cities, the demolition of unremarkable buildings and the purging of their inhabitants is a story so commonplace that it requires a trained eye to distinguish one from the next.

Mabel Duffy, Myrtle Stern, and the May Day marching band occupy a major intersection in the East Liberty neighborhood of Pittsburgh. They joined dozens of Penn Plaza residents and supporters in 2017 to protest publicly subsidized luxury apartments and demand that the city uphold fair housing practices. Photo courtesy of Jason Vrabel

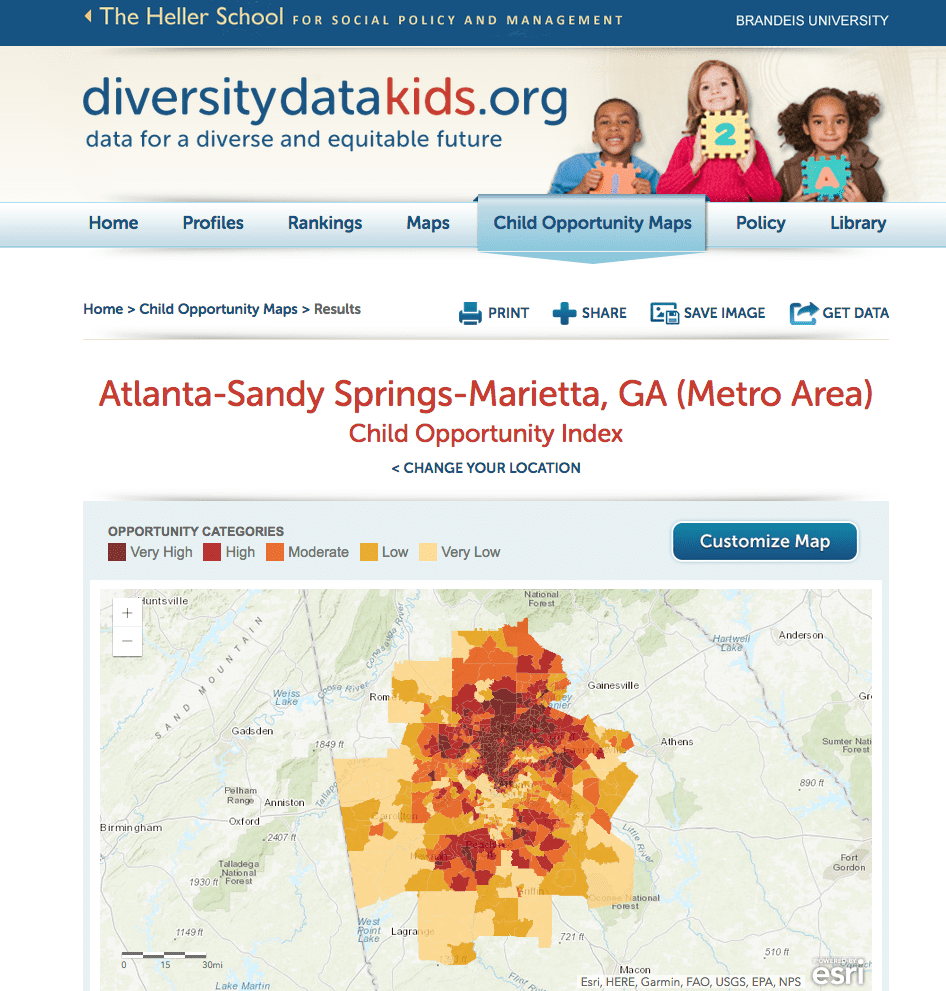

This story is not about poor people getting kicked out of a building because the times are changing and a more fashionable real estate opportunity has come to town. This story is about the “new Pittsburgh”—hailed as a 21st-century urban Cinderella story, but described by longtime Pittsburgh resident Mel Packer in his testimony to the city council as a “hemorrhaging patient on the operating table.” Indeed, Pittsburgh was laid bare and cut open for all to see during these two years. Immediately visible is a housing market tantamount to organ failure: a city with 155,000 housing units cannot absorb Penn Plaza’s 200 evicted tenants, even with the herculean effort of countless people working around the clock. Pittsburgh’s shortage of 20,000 affordable housing units is not merely an often-cited statistic, but represents a collection of real people with names.

Less visible is a city government––whose immune system has been weakened by antiquated, development-at-any-cost policies––that is unable to shake off an acute illness caused by an aggressive real estate company.

More than 50 people were working on the relocation effort as the two-year Penn Plaza crisis drew to a close in March 2017. In an official capacity, a small team scoured the region for apartment availabilities, coordinated leases and security deposits, and tracked where everyone went. Additionally, an unsanctioned coalition of volunteers pressured government agencies and real estate developers to intervene, while providing comfort and care to residents whose condition ranged from scared, frustrated, and angry, to severely depressed and devastatingly sick.

During Penn Plaza’s final three months, I watched this multi-layered effort unfold—flawlessly coordinated at times, cross-purposed at others—day and night. With few exceptions, the local news media seemed loath to step foot inside the building, instead aiming their collective focus on courtroom dramas involving developers and city officials.

Escalation

In late January, Mabel sorts through piles of apartment listings, awaiting a ride to visit her daughter Debbie, who is terminally ill. Mabel has already buried one of her two children. Myrtle sits nearby, looking out the window as roaring chainsaws cut into a birch. “Why they got to do this?” Myrtle exclaims. “We still got two months! It’ll take them one day to cut all those trees down, so why they got to do this now? They just trying to harass us. They want us out. But they don’t scare me.”

Mabel holds some scraps of paper up to the light. “There’s a couple places here I’m going to call about tomorrow. One’s in Hazelwood. I don’t know nothing about Hazelwood.”

Two days before, LG Realty’s Preliminary Land Development Plan (PLDP) for high-end apartment projects atop a Whole Foods Market had been unanimously voted down by the City Planning Commission. With approximately 100 opponents of the plan in the room, the commission cited, among other concerns, a lack of community engagement on the part of the developers.

Lourdes Sanchez-Ridge, the city’s solicitor, issued an order demanding that all actions constituting a “furtherance of the PLDP” stop immediately. Some of the trees occupied part of the public right-of-way, and LG Realty was fined $42,000. Despite this, a construction crew arrived inside the building the following Monday to begin interior demolition in vacant units.

The remaining Penn Plaza residents are scattered across seven floors, including the basement, and demolition activity is evident on each floor. Inside the vacant units, rolls of torn-up carpet are stacked in bathtubs; closet doors, cabinets, and toilets have been removed. Windows are sealed with plastic sheeting and adhesive spray, and empty cans of Poly-Tak litter the apartment floors.

Beneath the carpet is tile—broken and scattered in several units—that contains non-friable asbestos. The doors of dozens of units have been replaced with the same plastic sheeting as the windows, but are unsealed along the bottom; wherever original doors remain, the thresholds have been removed, leaving a one-inch gap at the floor. Steady drafts can be felt from the hallway outside every vacant unit. Bits of debris and tile litter the corridors, tracked by passing residents into their own apartments.

LG’s attorney, Jonathan Kamin, will repeatedly state in the weeks ahead that the residents’ complaints are specious and that no demolition has occurred.

The floor-to-ceiling windows in the fifth-floor corridor are also sealed with plastic and yellow tape. The air is heavy with odors from the Poly-Tak spray. O’Harold Hoots and his wife, Karen, are in the hallway complaining to Mabel and Myrtle about having trouble breathing.

“I can’t take it here anymore. My heart is pounding and it never used to do this,” says O’Harold. He’s found a new place a few miles away for himself, his wife, and their son, but the two-bedroom unit is barely 600 square feet and he wants to keep looking for something bigger. “I don’t know what to do. After what happened last night, we’ve got to move as fast as we can,” he says, pointing down the hall.

The last unit on the floor belongs to Malik Jones and his son, Malik Jr. “I heard all this pounding and came out to see what was happening,” O’Harold says. “The son was beating on the door, screaming for his dad.” A maintenance man opened the apartment and Malik Jr. found his dad on the floor, dead. “I can’t imagine if my boy—. This isn’t right. Something’s not right.”

Although LG Realty managed Penn Plaza for decades, the company is not in the residential real estate business; it’s in the strip mall business, making Penn Plaza an outlier in its portfolio. LG’s website lists the 42 strip malls it owns; when combined, they amount to nearly 4 million square feet (or 92 acres) of leasable retail space, which is larger than the Pittsburgh International Airport terminal building. The federal subsidies that financed the construction of Penn Plaza in the 1960s required that the owners maintain federal affordability rent limits for 40 years. Upon their expiration in the early 2000s, LG gradually reduced the number of occupied units by not renewing leases, and Penn Plaza evolved into a mixed-income building. About 20 percent of the tenants used Section 8 Housing Choice Vouchers to subsidize their rent, while others paid amounts closer to market rate. Even the market rents were comparatively low, making the complex what is commonly known as “naturally occurring affordable housing.” The evicted tenants included students and retirees, salaried and hourly workers.

Two weeks after his father’s death, unable to pay the next month’s rent, Malik Junior left Penn Plaza and his whereabouts remain uncertain.

The Volunteers

Forty-one days before the March 31 eviction deadline, Helen Gerhardt of Homes for All Pittsburgh, and Chandana Cherakupalli of Pittsburghers for Public Transit, door-knock in Penn Plaza. They’re part of the Penn Plaza Support Group that meets weekly to provide for residents’ needs, and today they’re offering electric blankets and space heaters. Jerome Jennings, 64, says he’s moving to a 300-square-foot efficiency. Chandana tells him that that the support group can provide boxes and packing supplies, a moving van, and volunteers to help carry it all.

“Thank you, I appreciate that,” he says. “I’m leaving most of it behind.” Pointing to his abdomen, he adds, “Eight months. I don’t need much.” Jerome has liver cancer.

The next day Helen and Chandana are back with a dozen volunteers to assist two tenants who are moving that day. Geary Rivers, 70, stands by his living-room window, dazed by the number of people who have come to help. On the sill are his POW cap and his Bible. Geary’s new apartment in Wilkinsburg is much smaller. “It’s only temporary,” he says, tapping his Bible. In Geary’s living room, I found Maranie Staab, two cameras around her neck, capturing Geary’s last day there for a moving profile about Geary for PublicSource. From January until March 31, the day the doors were permanently locked, Maranie was the only reporter I encountered inside Penn Plaza.

In her Penn Plaza home before she relocated to another residence, Myrtle Stern looks through photographs. Photo by Maranie R. Staab

One floor below on the basement level, Jackson Hart* has lived at the end of a long corridor for more than a decade. He has multiple sclerosis and uses an electric wheelchair. Though still in his 20s, Jackson is wearing a World’s Greatest Granddad sweatshirt. He can’t stop smiling. “I’m excited,” he says. “I’ve been the only one down here for so long. It gets real lonely . . . and sometimes a little scary.”

Helpers march up and down the hall, moving what would end up filling most of a donated U-Haul: a special needs bed and mattress, wooden TV stand, two portable toilets, a small safe, a recreational slot machine, a small chest freezer, and garbage bags stuffed with clothes. Jackson isn’t worried about the unfamiliar new neighborhood. “There are a lot of little stores nearby, and the grocery store is right there. That’ll make it easy for me not to have to take a bus to get groceries.”

Jackson’s new building is owned by the city’s Housing Authority, where the level of maintenance is higher than at Penn Plaza. The full-time security guard takes his job seriously and checks the arriving volunteers’ driver’s licenses. The two without identification must stay outside on the loading dock.

Jackson’s one-bedroom apartment overlooks a railroad bridge and has a remarkable view of the downtown skyline across the river.

Two volunteers are in the bedroom assembling Jackson’s bed. Six others, standing or sitting on boxes, are gathered around Jackson, watching golf on TV. “I guess we’re all set,” his medical assistant, Marlene, says. “Thank you, everybody.”

For a long, curious moment, no one moves.

For months Penn Plaza has been unending chaos: chainsaws slaying trees and construction crews dismantling apartments; maintenance crews removing appliances and tenants banging shopping carts in elevators; with debris, dust, and chemical odors; ambulances and moving vans; inspectors, community organizers, volunteers, and lawyers; apartment applications, Housing Authority forms and eviction reminders.

For 15 seconds, Jackson’s apartment is tranquil.

At a commercial break everyone begins to stir, waiting their turn to offer Jackson handshakes, hugs, and good-luck wishes. Jackson thanks each one. “I feel sad to be leaving those other folks behind and I hope they all find someplace soon.”

A few items were left behind in Jackson’s old apartment, the biggest of which were two old wheelchairs he no longer used. LG Realty deducted $450 from Jackson’s security deposit.

The Supporting Cast

On Feb. 21, Mabel, Myrtle, and O’Harold join other residents and community organizers on the steps of the City-County Building. They demand a halt to the ongoing demolition and ask developers of nearby luxury housing to make their vacant units available to Penn Plaza tenants.

The following day, Mayor Peduto wrote in a letter to local housing developers, “If you each are able to accept just a few residents, we can make sure that every resident of Penn Plaza is treated with respect and are provided the opportunity to continue to live in East Liberty.” By day’s end, the city filed a complaint against LG, alleging it violated the conditions of the MOU intended to guarantee safe and sanitary conditions at Penn Plaza.

While door knocking, Helen made contact with Henry Davis, a Vietnam veteran who is ill. Davis’s apartment was in troubling condition, indicating that he was in dire need of more support for daily living.

The support group reaches out to IAS and Neighborhood Allies to convey the gravity of Henry’s situation, but they already know. If Zak Thomas, senior program officer for affordable housing and lending at Neighborhood Allies, were to walk into a Penn Plaza Support Group meeting, most residents wouldn’t know who he was, but Zak knows who they are.

In a March email exchange, Zak wrote that he was fully aware of Henry’s condition and that IAS made several attempts to connect him with the VA to obtain a VASH voucher (a housing subsidy for veterans). When Henry missed appointments and phone calls, a function of his severe alcoholism, Zak then connected him to a sponsor from another group called Soldier On. IAS involved the Housing Connector, a local housing resource, spoke with his doctor at the VA, and made regular visits to his apartment. “We’re convinced it’s not enough,” he wrote.

For six months, Zak had been presenting Henry’s plight (as well as the plights of other residents coping with mental illness or addiction) at monthly meetings with Allegheny County’s Department of Human Services and its Local Housing Option Team, with the hopes of finding solutions. “It still doesn’t seem to be working, so we need to keep looking,” he wrote.

Games of Chance

On March 4, it’s sunny and 22 degrees. Six volunteers have gathered in a patch of sun in the Penn Plaza parking lot at 9 a.m., awaiting Two Men and a Truck, a company hired by IAS to move Doris Webster’s* heavy furniture and other belongings. With volunteers assisting a professional crew, the move takes seven hours. Furniture, boxes, and bags of clothes leave only a narrow maze for the 80-year-old Doris to navigate in her new home.

The weather warmed considerably for the Hoots’ move the following day. A new slate of volunteers twice fill a U-Haul headed for a 600-square-foot third-floor apartment in a building without an elevator. O’Harold and Karen stay behind to pack, and Doris appears in the doorway, having returned to the building to say farewell. “I love you,” Karen says to her.

“I love you more,” Doris replies. Her eyes fill with tears as she takes one last look at the Hoots’ apartment, “Seeing you move is harder than seeing myself move.

Downstairs in her near-empty apartment, Doris examines the crisp brown leaves of a potted palm that’s a foot taller than she is. “I hate to leave it,” she says. “It was only an inch tall when I got it.” Pointing to a young green shoot growing near the top she says, “See this here? This tells me it’s still living.” She snips off the one-inch shoot and takes it to the sink. “Maybe this little bit will grow in water.”

From outside, Penn Plaza is seen for its windows covered in plastic, glowing at night from the few lights that are left on; its empty parking lot; its lifelessness—a dead building to be thrown out. But inside there is life. Inside is grief, fear, and at times, madness. But shoots of hope grow: from every new apartment IAS finds; from every volunteer who shows up; from every act of civil disobedience that forces the people of Pittsburgh to see and hear the otherwise invisible and silent inhabitants of Penn Plaza. Hope will not prevent Doris or anyone else from being discarded, but they’ll carry it with them in small ways.

While Doris places her hope in the lone surviving bud on an otherwise long-dead plant, LG Realty places its hope in a flagship store for a national purveyor of high-end groceries. LG Realty’s power ultimately rides on the buying and selling of commodities. To its miles of corporate strip malls that sell everything from cat food to power tools to haircuts, it has now added the people of Penn Plaza.

Off to Verona

It’s March 8 and Myrtle, Mabel, and Helen are on their way to a meeting at the City-County building with Kevin Acklin, the mayor’s chief of staff, to discuss the outcome of the mayor’s letter to developers. In the lobby, Mayor Peduto passes directly behind them. “Mr. Mayor!” Helen calls.

The mayor stiffens, but then greets them warmly, shaking hands. “I did pavement for you!” Myrtle says, meaning that she went door-to-door during his campaign.

“Yes,” he says, “I remember your face.”

“I got to go out to Verona,” she says. Verona is a borough seven miles from Penn Plaza. “I don’t want to go out there! My family, my doctors . . . they’re all in East Liberty.” The commute from Verona to East Liberty involves two buses and takes an hour and 10 minutes.

“I don’t want you to have to move to Verona,” the mayor replies. “I think we’ve found some options to keep you in East Liberty.”

Myrtle enters the meeting eager to learn what this means. On her way out, Myrtle says, “Waste of time.” The “option” is a temporary stay in the Mellon’s Orchard apartment complex, a few blocks from Penn Plaza. It’s owned by East Liberty Development Inc., a nonprofit community development corporation. It, too, is slated for demolition in about a year and a half. Instead of making available vacant units in their own buildings, the developers who received the mayor’s letter passed the hat and collected $50,000 to make habitable several unoccupied units at Mellon’s Orchard.

The next day, at the corner of Penn and Centre Avenues in East Liberty, the sounds of a tuba, saxophone, and trumpet mix with a steady drumbeat echoing off building facades as members of the May Day Marching Band begin warming up. It’s unseasonably warm and the sun shines upon the 100 people gathered in front of the luxury Eastside Bond apartment building to protest unfair housing practices and publicly subsidized luxury apartments. News crews and a handful of police officers mingle with the crowd, which ranges in age from children to seniors.

The group marches into the high traffic intersection followed by the brass band. Some carry couches, chairs and tables, while others fan out to block incoming traffic. The next 30 seconds are tense. Motorists’ confusion turns to anger and horns blare while drivers swerve to get through before a square-shaped human barrier is fully formed. The police move to where protesters stand face-to-face with lines of cars and trucks, while the group sets up a furnished “public living room” in the middle of the street.

As police reroute traffic away from the intersection, the hostility from motorists gives way to energized speeches from Helen, Myrtle, and several others who call upon the city to uphold fair housing laws and provide immediate relief for those being displaced.

Myrtle and Mabel are sitting on a couch in the middle of Penn Avenue. “There’s not going be nothing for us in there,” Mabel says, pointing to the Eastside Bond building behind her. “I made up my mind. I’m going out to Verona,” she says, referring to the Arthur J. Demor Towers, a project-based Section 8 apartment building that has accepted her application. “I’ve had all of this I can take. I told Myrtle to come out there with me but she doesn’t want to.”

“That’s miles away!” Myrtle snaps. “When I’m not feeling good, I go see my daughter and my grandbabies. How am I going to do that with that one bus that goes out there?” Mabel persuades her friend to visit the building in Verona the next day. “It’s nice, I’ll give it that,” Myrtle says afterward. “And they got Bingo. I bet I can show them a thing or two about Bingo.”

The following week, Mabel, Myrtle, and two other Penn Plaza residents signed leases at A.J. Demor. To do so, they had to give up their tenant-based Section 8 vouchers, which will be difficult to get back if they need them. By March 15, all of the remaining 11 tenants had secured new residences. IAS hired Two Men and a Truck for five moves, one that week and four the next, including Mabel’s and Myrtle’s. The mood inside IAS’s office lightened. “It’s definitely not ideal for everybody,” Jim Hoover from IAS says, “but I think we have things under control.”

On March 21, Helen notified the support group that the situation was very much not under control. While moving out an elderly man named Vic, Two Men and a Truck claimed to find bed bugs on their truck and canceled their contract with IAS, forfeiting nearly $10,000 in fees. “We looked through all of Vic’s things—mattress, couch, everything—we didn’t find any bugs,” Jim says in disbelief. “I don’t know what happened.”

The final eviction date is nine days away and the relocation team has lost its movers. Residents will forfeit their security deposits and move-out payments if their units are not empty, and will not be able to afford deposits on their new homes.

While the search for a new moving company is underway, residents and the support group descend upon Whole Foods at lunchtime on a Saturday. Throughout the store, they distribute fliers to customers, explaining that as an anchor tenant, the grocer bears some responsibility for the evictions. They want Whole Foods to either back out or pressure LG Realty into including affordable housing in its redevelopment plan.

Mike Moves Pittsburgh steps in to move the remaining nine residents. On March 27, two vans are parked at Penn Plaza’s front entrance, while dollies and shopping carts rumble through the halls above.

Mabel is wearing a pink sweatband across her forehead as she furiously vacuums her near-empty apartment. “I don’t care how they treated us . . . I’m leaving it cleaner than I found it.” She wipes the windowsill with scented cleaner and a cloth. “It smells nicer now,” she says, before flopping into the last remaining piece of furniture, her green armchair. “This is my comfort spot. I’ve been living in this chair.”

Mabel and Myrtle’s belongings are loaded onto the same truck and are sent off to the same building, far from home.

A New Home

On March 28, thousands of pear trees have flowered overnight, and the morning fog makes it hard to tell where the upper floors of A.J. Demor Towers end and where the sky begins. Myrtle is settled in her recliner in the corner of her new living room, surrounded by dozens of cardboard boxes and full garbage bags. Her door is open when I arrive.

“Fresh air! They got fresh air out here!” she shouts. It’s still “they” and not “we,” but she’s wide-eyed and smiling. “Had the windows open all night.” The windows behind her look out over the wooded Allegheny River Valley.

Diann Manuel, another displaced Penn Plaza resident, appears at her door. “Have you seen the balconies yet, Myrtle?”

The two women stroll to the end of the hall. Passing their new neighbors’ doors, adorned with Easter wreaths and flowers, Myrtle says, “I’m going down to the dollar store to get some decorations and a welcome mat.”

“How about this view?” Diann says, as they sit by the iron railing, looking through the still-bare trees to the fog rolling over the surface of the river. “It’s covered, too. I can play solitaire out here,” Myrtle says.

Returning to the elevators, Diann and Myrtle see a flier for Bingo Tuesdays. “Diann, you coming to Bingo with me tonight? I’ll show you how it’s done.”

“Maybe I’ll watch,” Diann says. “I don’t like games of chance.”

“You don’t like games of chance?” Myrtle snaps. “What do you think the last year was? Your whole life is a game of chance!”

The Last Day

On March 31, Penn Plaza is nearly silent. A headline in the Post-Gazette reads: “Whole Foods pulls plans for new East Liberty store”. The rain falling early in the morning would not let up until night. Mike Moves’ crew is again joined by volunteers who fan out to the last four occupied apartments.

Vivian Campbell’s fastidious ways are evident; she and her belongings are organized and ready to go. Leaning against the wall is a Louisville Slugger bat engraved with Bill Mazeroski’s signature. “I got that at my first-ever game at Forbes Field, June 9, 1967,” she says, wearing a bright yellow Pirates T-shirt. “I loved ‘Maz,’ but Matty Alou was my favorite. The Pirates traded him for Nellie Briles in 1970, and I never forgave them for that.”

It’s 4 p.m. and the rain has slowed. Vivian’s new apartment is only temporary, but will allow her to stay in the neighborhood her family has lived in for five generations for a little while longer.

By 6 p.m., all of Penn Plaza’s 200 hundred residents have a new address; most have a new ZIP code.

The next day, more than 100 people gather on a cold and wet first day of April, not to celebrate, but to mourn the loss of Penn Plaza and its residents. The band plays a dirge as the group marches from the site of the “living room” protest, recognizing the displaced and deceased along the way, and acknowledging the many black-owned businesses that have been replaced with high-paying corporate tenants, or vacancies.

Randall Taylor refers to himself and the others as “Penn Plaza refugees.” Many of them have made “hard landings,” he says, and to this day sleep on the couches of family and friends. The most recent transplants will have their share of hardships, too. Six weeks later, O’Harold Hoots’ family is feuding with their new neighbor. Myrtle hasn’t received her move-out payment or her security deposit, a direct violation of her lease with LG Realty. A woman asked Jerome Jennings if she could charge her phone in his apartment. Seeing that she was wearing a hospital wristband, he agreed. He left the room, and when he returned she was dead of an overdose. (The police fully exonerated Jerome from the tragedy.)

A vase of flowers sits in the middle of Myrtle’s dining table, and a menagerie of ceramic animals is arranged on her coffee table. She holds a deck of cards and gazes out the window at children playing outside at a daycare center. “I watch them every day. They’ll be going in for their naps soon,” she says. “If something opens up in East Liberty, I’d be back in a heartbeat. For now, these kids make me happy. But I don’t belong out here. I belong in East Liberty.”

Mabel is more accepting of her new home, considering it permanent. “I can’t see my daughter as much being all the way out here,” she says. “I lived in East Liberty more than 40 years and didn’t even know where Verona was. I never thought I’d end up out here, but I guess I’m here to stay.”

*Editor’s note: The names of some residents have been changed to protect their identities.

Thank you Jason for taking the time to write this enlightening, but, heart-wrenching article. Your involvement with these precious people had to be difficult and somewhat disturbing at times.

Thank you Helen for reading the story. They are indeed good people who deserve better. Jason

Wow, very powerful and disturbing. Thank you for your faithfulness to Myrtle, Mabel, and each resident in telling this story.

Thank you for reading, Joy. The support group is continuing to work with them on finding other options that will give them some peace. Jason.

Hello I noticed that the land has not been developed as of yet. I am not sure if this information is accurate, can you tell us if Whole Foods pulled out of the deal and were those individuals made homeless for no reason? what is to become of the land?

Hello lee lee. That’s correct. The property has been cleared and tied up in a legal battle for some time. An “agreement” was reached that was very much unsatisfactory to many involved. It has been a very complicated process, which I’ve written about here: https://downstream.city/news/cutthroat-island-part-one/. Whole Foods did pull out, but it was later reported that they are very much still a viable anchor tenant once the project moves forward. It’s important to note that Whole Foods is now owned by Amazon, which has identified Pittsburgh as a possible location for their second headquarters. Jason.

I wish I understood more about this.

Hi Hcat. Me too! I’ve written more about what’s happening here: https://downstream.city/news/cutthroat-island-part-one/. Jason.