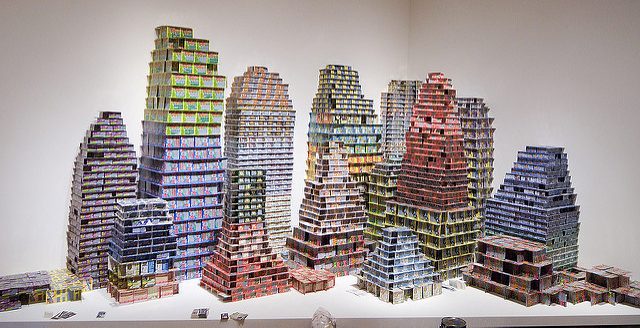

CHANCE CITY, installation composed of losing lottery tickets. Photo by Smithsonian Art Museum, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

In 2014, New York City Mayor Bill De Blasio pledged to preserve and develop 200,000 units of affordable housing during his term. To accomplish this, he championed New York City’s Inclusionary Housing program, better known as the “housing lottery”.

For the past two years I’ve worked as a housing lottery project manager for a small affordable housing developer and have found that, in spite of De Blasio’s bold initiative, the program often fails to efficiently and adequately serve the very people for which it has been designed.

It’s important that the program’s policies and structuring are examined in light of De Blasio’s race for reelection this year. Here are a few simple reforms that I believe could quickly improve the program here and inform similar programs elsewhere.

-

Unreported income is Real. Don’t Ignore It

The most common income limit on Inclusionary Housing projects in New York City is 60 percent of the Area Median Income (AMI). This means that the plurality of affordable 1-bedroom apartments is marketed toward New Yorkers earning roughly $35,000 annually (for a one-person household, you are eligible if you earn $33,875 to $40,080 based on current guidelines). While there are many individuals at this AMI level, there are policies that bar this population from being offered an inclusionary unit.

One common policy that rejected many, otherwise flawless, applications was the restriction on recognizing unreported income-essentially, applicants that earn their income off the books (i.e. from child care, food service, or home cleaning jobs), and do not report it to the IRS are immediately barred.

It’s important to note that one of the purposes of Inclusionary Housing, a tax-subsidized affordable housing development stimulus, is to supplement the waning supply of naturally affordable housing stock left in New York. In New York’s unsubsidized rental housing market, it is often possible to secure a lease-signing without providing a tax return or paystubs. However, low-income tenants that are paid in cash are often subjected to undesirable housing conditions in these cases (i.e. widespread building code violations, few tenant protections). Thus, under-the-table service workers are some of the city’s most vulnerable populations.

If the city is to be successful in providing quality housing for low-income earners, policymakers ought to consider the many low-income earners that do not report their income. It may be against the law, but it is a matter of fact that many low-paying and/or sporadic jobs are often compensated with cash. If low-income applicants provide documentation proving that their earnings are within the allowable income bands (let’s say about $30,000), then their incomes should be recognized.

Many of these jobs are essential to maintaining a standard of living for all New Yorkers around the clock. While legal and political opinions may splinter on this issue, I believe that low-income earners would become more likely to report their income if they were allotted quality affordable housing. It could be stipulated in new Inclusionary Housing leases that the tenants are required to report their incomes after move-in. Tenants that do not yet report their incomes could be connected to financial counseling for assistance. Existing tax incentives, such as the Earned Income Tax Incentive (EITC), make this policy more likely to be successful because many truly low-income tenants will not be slapped with heavy taxation.

2. Remove Preferences for High-Earning Neighborhoods

Several types of applicants are given priority in the housing lottery. One such preference gives extra weight to applications from residents of the neighborhood where the inclusionary building is located. The preference does not distinguish between low-income and high-income communities; it is applied to every neighborhood citywide, which means that if an inclusionary building opens in SoHo, a neighborhood filled with luxury housing, residents that already live in SoHo are given preference for the new affordable units. In effect, this obstructs thousands of other applicants from low-income communities that would surely benefit more from relocating to SoHo. A spate of recent lawsuits agree that this policy reinforces patterns of segregation.

City officials ought to restructure this indiscriminate preference with informed census data. To determine the level of local need for affordable housing preferences, you might consider the median income earnings of the local Community District at the very least.

The community preference is beneficial in some situations, of course, such as in neighborhoods with large tracts of low-wage earners and high rates of rent burden. By reserving affordable apartments for nearby applicants in low-income districts, developers are fulfilling a greater commitment to the localities in which they operate.But time and money are wasted if the blanket policy requires that a developer give preference to the existing residents of a wealthy community.

One inclusionary housing building in TriBeCa, one of the city’s highest earning neighborhoods, closed its marketing period two years ago. The administering agent that was commissioned with vetting the housing applicants was required to invite each and every applicant from the locality to come in for an initial interview. Call me presumptuous, but I think the only applicants earning between $30,000 and $36,000 in TriBeCa are recent private school graduates working entry-level jobs while living at home in their parents’ multimillion dollar lofts—not exactly the city’s neediest residents. I will note that I have heard first-hand from developers who’ve suggested that they endorse this blanket-style preference because it grants an opportunity to find “safer” tenants for their new buildings before turning to “less safe” applications. In effect, this policy may be enabling developers to impede the pipeline of affordable housing applications in favor of younger, wealthier, and whiter residents.

3. Set Guidelines That Distinguish Between Affordable Rentals and Condos

It is peculiar that the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) has not yet released a concrete set of policies that are specific to homeownership. Currently, HPD’s compliance managers default to policies that were designed specifically for affordable rental buildings, not affordable condominiums. It must be stressed that signing a one-year affordable lease and purchasing an affordable condominium are two very different undertakings. Whereas rentals are often marketed toward deeply low-income earners, condos are sold to applicants that are able to pay the required down payment from their own resources. Where rental applicants may be considered with a FICO score lower than 580, homeownership applicants’ credit reports must be vetted based on guidelines set forth by a bank. HPD has not yet consulted with an accredited lender to determine standard credit criteria for inclusionary homeownership projects.

I found that compliance managers at HPD were confused when my office would submit a homeownership application. As a result, regulations were applied somewhat inconsistently and often on a case-by-case basis. Essentially, city officials were making the rules up as they went. And if my office called to say that a bank representative had already approved a file for a mortgage, then the file was typically approved.

I’ve had discrimination charges thrown in my face during my tenure as a project manager. Though the charges were unfounded, I fear that HPD may face similar allegations if a curious applicant decides to pay more attention to their vetting process for affordable condos. In order to ensure that compliance managers are applying consistent and befitting rules, HPD must be tasked with creating a separate set of policies to regulate its inclusionary housing affordable homeownership program.

4. Create a Centralized Database of Lottery Winners

After applicants have spent weeks waiting to sign their new lease or close on their home, most of them are quite happy from what I’ve heard. In fact, some of the applicants are so happy to be paying below-market rents for prime real estate that they continue to try their luck with more lotteries.

There is a group of successful applicants who have already won in the lottery rat race, and realize that they are likely eligible for another apartment. Some have even learned that there is nothing in place to restrict inclusionary housing tenants from signing more than one affordable lease. These observant people realize that there is no centralized database of lottery winners’ names and they are able to apply for other lotteries. If they win again, they are likely to sublet one of these apartments to friends or family, which reduces the supply of a public good (the affordable unit) and transforms it into a private good (an unauthorized sublet). Sublets are prohibited by inclusionary housing leases, but tenants know that HPD and administering agents do not have the ability to carefully monitor what is done with an affordable unit once it is signed for.

The only way that a tenant might be discovered violating their lease is if building management realizes there is a new tenant paying the rent or passing through the lobby.

I found that there were at least a dozen applicants who would reapply to each and every new housing complex. These applicants did so in spite of the fact that they had already moved in to a subsidized apartment. While HPD has published a guideline to prevent existing homeowners from taking advantage of the inclusionary housing program, they have yet to deter current affordable leaseholders from hitting ‘apply’ to every housing project in the city. In theory, anyone that continues earning wages at the 60 percent AMI level can sign for a dozen affordable units in the city and there is no provision to stop them.

Some hard-working people evade taxation. Some people would benefit from leaving high poverty neighborhoods more than others would benefit from being subsidized to remain in desirable ones. Some people may allege that the city is discriminating against them because there is no statute to determine how their condo application should be handled. Others will ‘win the lottery’ and try to repeat their success for every member of their extended family.

Given the commitment that the mayor has made to low- and moderate-income residents, city officials ought to consider the realities on the ground. As other cities look to New York City’s inclusionary housing policies to learn and borrow from, it is vital that the program is cleaned up and made worthy of modeling.

Comments