Elderly low-income renters have the greatest needs. They will deservedly receive the most attention in the coming years as governments and nonprofit housing providers scramble to cope with the steady growth in the number of elderly households who are poor enough to be eligible for federal rental assistance. There were 3.9 million of them in 2011, according to a report from Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies. By 2020, that number is predicted to rise to 5.2 million.

The plight of elders who own their homes may seem less dire, but many are paying more than 30 percent of their income for housing. Many are living in houses they cannot afford to heat or to repair. Elders are also heavily represented among the low-income homeowners whose assets plummeted during the recession, which wiped out nearly a third of the equity that low-income homeowners had in their homes. That is lost wealth that might have eased the retirement of many elders.

Aside from worrying about the personal welfare of our elderly neighbors, there is also a set of place-based concerns surrounding elderly owned homes that warrant closer attention from government officials, city planners, and community activists. These are issues of condition, affordability, and tenure. Will elderly owned homes be adequately maintained? Will they be affordably priced, allowing younger families of modest means to move into them when the current occupants leave? Will they remain owner-occupied or be snatched up by absentee landlords?

Although such questions are widely relevant, they have special urgency for those rural towns, inner-ring suburbs, and even some inner-city neighborhoods where a large percentage of the housing stock—and often a majority of the locality’s homeownership—is presently owned and occupied by persons older than sixty years of age. What happens to that housing over the next ten years will largely determine the developmental trajectory of these places. In particular, who gets to own and manage them as they are passed to the next generation will affect whether the locality’s future is one of stability or change, for better or worse. In some places, it is the coming disposition of elderly-owned housing that will tip the scales toward deterioration or gentrification.

These transitions can be left entirely to the market. Matching sellers with buyers and setting a price agreeable to both is what markets do best. This bridge to the future works fairly well, in fact, in more affluent communities where elderly homeowners have enough savings in their accounts and enough equity in their homes to take care of their houses (and take care of themselves) until they voluntarily move into smaller dwellings or retirement communities. As their houses become available, they are quickly and profitably purchased by young professionals with the wherewithal to transition into bigger houses and better neighborhoods.

This is a rather idyllic picture, however, which does not represent the reality of many people or many places where the bridge is broken. Elderly homeowners of modest means are often stuck in houses that are too big and too costly to maintain, but moving elsewhere is more difficult and costly than staying where they are. Younger homebuyers of modest means are locked out of houses that elders would gladly sell, sooner or later, but elders are still living there and, anyway, their houses are too expensive for most families to buy.

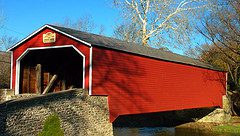

What’s needed is a covered bridge, a nonprofit program somewhat insulated from the market that is capable of facilitating the conveyance of owner-occupied homes from one generation to the next, while providing protection from troubled waters below and stormy skies above. The design specifications for constructing such a program would include the following, at a minimum:

- Elderly homeowners who want to move must be provided with a ready buyer and a fair price for their property.

- Elderly homeowners who want to stay must be able to do so, remaining in their homes for an agreed-upon period of time, ranging from a five-year occupancy to a life estate.

- Replacement housing must be available and affordable for elderly homeowners when they decide to move, now or later.

- Homes that continue to be occupied by elders must be inspected and improved for health and safety, modified for accessibility, and supported with on-going maintenance services during the elders’ tenure.

- Homes that are presently owned by elders must be affordably priced for purchase by younger homebuyers of modest means whenever the housing’s elderly occupants decide to leave.

- The affordability of these homes, subsequent to their transfer to the next generation, must be preserved forever, preventing the loss of the large investment of public dollars and private donations that would be required to subsidize the exit of elders, the entrance of youngsters, and services to both.

The biggest barrier to creating such a multi-faceted program lies in finding (and funding) an equitable balance between serving the interests of elderly homeowners who need to sell high and want, perhaps, to stay as long as possible, and serving the interests of younger families who need to buy low and want to become homeowners as soon as possible.

Another prodigious and precarious feat of balance looms large. Any nonprofit organization that assumes responsibility for taking care of elderly owned homes until the day they are conveyed to new homebuyers must find a way to honor its promises while limiting its risks should elders remain in their homes for many years.

And that is only the housing side of the program. Elders who are aging in place are likely to need additional services and supports that a nonprofit houser, particularly one that has focused on homeownership to date, may not have previously provided or arranged.

In outlining such a grandiose scheme with so many hurdles, I am conscious of sounding a little like the 20th Century American comedian, Will Rogers, who was once asked by a newspaper reporter how he would deal with the wartime threat of German U-boats. “Boil the ocean,” Rogers replied. Taken aback, the reporter inquired, “But how do you do that?” Without missing a beat, Rogers said with a grin, “I’m just the idea man here. Get someone else to work out the details.”

I haven’t figured out how to build my covered bridge. I’m not even sure that it can be built. But surely there is someone out there who is capable of working out the details. And it’s gotta be easier than boiling the ocean.

(Photo credit: Flickr user Nicholas_T CC BY 2.0)

Comments