While both agree on social issues, like gay marriage, Booker has sought the beneficence of Silicon Valley and Wall Street for their money and ideas. Williams, a progressive growth and redistributionist in the mold of Jesse Jackson, the late Chicago Mayor Harold Washington, and New York’s Mayor Bill de Blasio, believes change comes from the grassroots up, by building community-based movements.

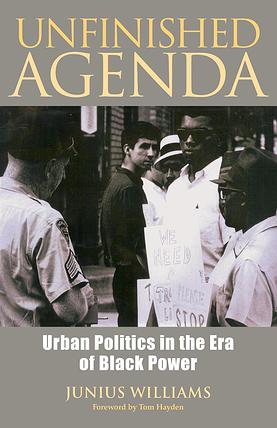

Williams lost his run for Newark mayor in 1982, but he remained in the trenches as a street organizer, lawyer and public school advocate. His persuasive, engaging political memoir, Unfinished Agenda, Urban Politics in the Era of Black Power, is a road map for addressing poverty, failing schools and crime. Williams weaves three separate narratives into one insightful personal story.

His diary begins in the Jim Crow South of Richmond, Va., where he grew up in a supportive, well-educated extended family that pushed academics. As a senior at Amherst College in 1965, he joined the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the heart and soul of the civil rights movement, known for organizing dangerous local voter registration campaigns and demonstrations.

Before attending Yale, Williams went to Newark, where he joined Tom Hayden and other young radicals in a Students for a Democratic Society urban organizing project to mobilize black residents around bread-and-butter issues like housing, police abuse and schools. In 1967, after the Newark “Rebellion,” Williams formed a new group, the Newark Area Planning Association, which organized against gentrifying urban renewal plans that included a medical school. These struggles prepared his community to move beyond neighborhood organizing to a campaign to elect the first black mayor of Newark. Williams sees the period as a critical moment in his training for the next stage of the civil rights conflict.

The second narrative provides the reader with a political history of Newark from the 1960s until today, a city Williams helped shape. Working with local ministers and the Black Panther Party, he stopped a highway from running through Newark’s Central Ward and negotiated an agreement with the medical school that produced 1,000 new affordable homes and employment in well-paying construction and hospital jobs. His reputation earned him the job of managing the 1970 campaign of Newark’s first black mayor, Kenneth Gibson.Gibson appointed Williams, at 26, the head of Lyndon Johnson’s federal urban aid program, Model Cities. Once inside City Hall, Williams reveals the conflicts that developed between those who were elected to office and the people whose organizations elected them. He vividly describes the rivalries, alliances and betrayals. The same qualities that led Gibson to hire Williams—his intelligence, pedigree, street smarts and loyal following among residents—caused Gibson to fire him as a political threat.

The third narrative is his political analysis of urban power. Williams believes Newark suffers today partly because too many black politicians lost touch with the rank-and-file residents of its low-income neighborhoods and the grassroots community, faith-based and labor groups he and others built.

Elected officials, winning in low-turnout elections, made promises to improve housing, jobs and schools, but lacking the resources and political will, couldn’t keep their promises.

Building the kind of clout Williams envisions will be difficult since city mayors lost the influence they had in the past, and may require progressives to synthesize the conflicts between him and Booker. Booker seeks to empower and educate underprivileged children using charitable donations from wealthy entrepreneurs, vouchers and charter schools—a vision Williams believes is short-sighted. While he’s willing to work in the Democratic Party, Williams believes the only way to change state and federal priorities that will lift the poor and working class is by a progressive movement that builds on the power of grassroots independent people’s organizations.

Williams provides a template for the hundreds of young people drawn to his classes at the Abbott Leadership Institute and the Youth Media Symposium. He urges them to organize and push from the outside to hold politicians accountable.

Williams is an example of what one leader can do to inspire change in the city. He’s passing his knowledge on to the next generation, to keep the fires of resistance and imagination burning.

This book review originally appeared on NJ.com

I think it is interesting to note that while Mr. Williams grew up in a home that emphasized the importance of education and he was successful in his schooling and got through College and Post Graduate work, he seems to think that scenario doesn’ t work for low income minorities anymore. He now promotes “progressive” policies and redistribution of wealth to bring up the lower classes. He surely knows in his heart that this approach is just wrong headed thinking and that it only rings true with those looking for a hand out. Shame on him. Mr. Booker’s approach makes a lot more sense to me.