“Business moves away. So do the best young people. The population ages. The city becomes a backwater.”

– Richard Longworth, “City on the Brink,” Chicago Tribune, 1981

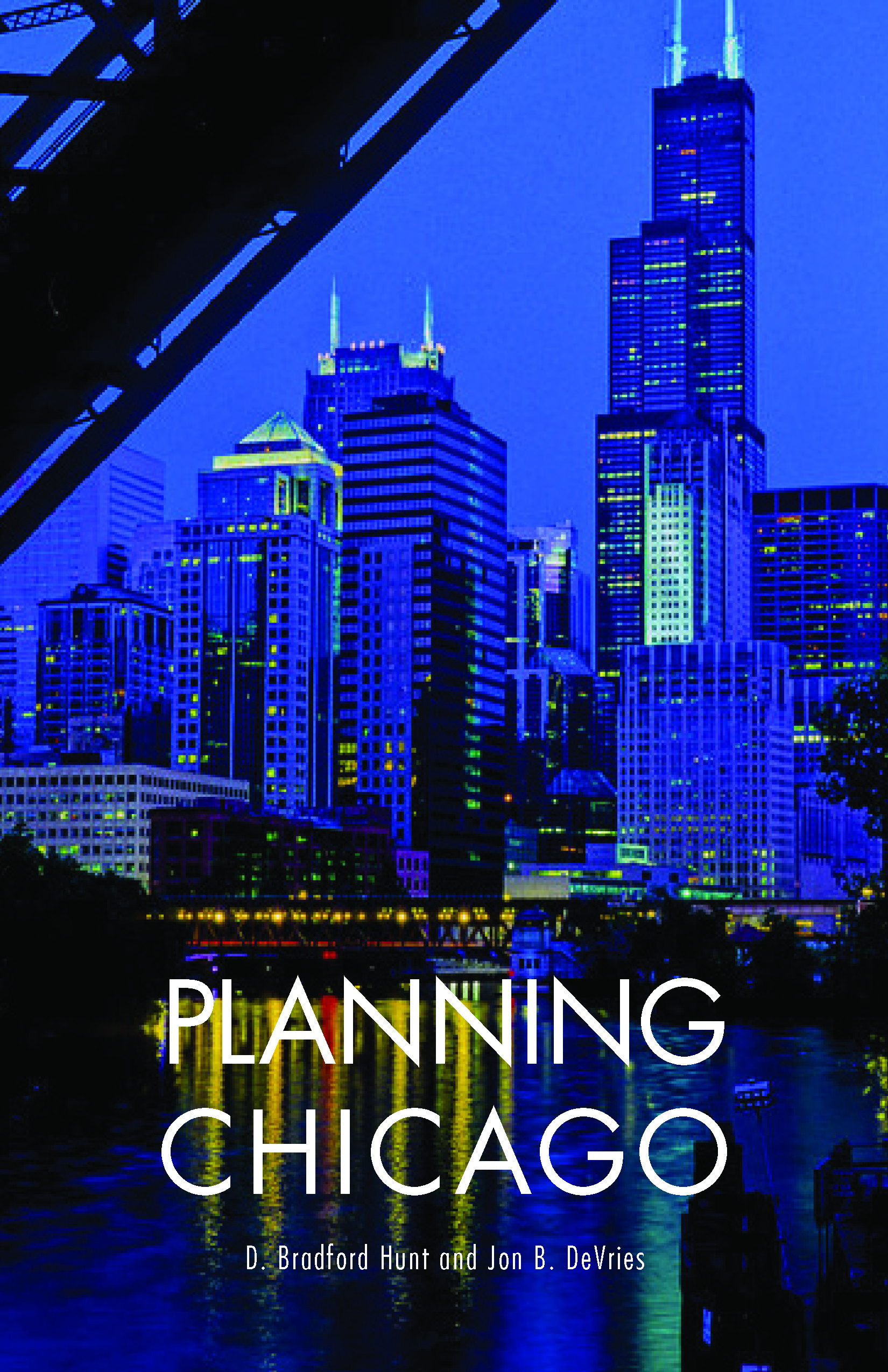

So goes the first extensive quote in the opening chapter of Planning Chicago by D. Bradford Hunt and Jon B. DeVries, published in May by the American Planning Association. This incisive economic analysis is as relevant to our communities today as it was over three decades ago. Perhaps it’s the key discerning factor between Chicago and Detroit, at least for now.

For those history buffs looking for the play-by-play on Chicago’s development since 1957, this book has it. For those of us still wondering what is in the future for community development wherever we call home, the book provides many lessons to ponder.

First, the personal disclosures: my community development career of almost 40 years, most in my home town of Chicago, coincides with much of the narrative shared by Hunt and DeVries. I know many of the cast interviewed or portrayed. Yes, I have a few quotes too, and my current organization is featured in the chapter on industrial policy.

My primary reflection is how much more we need to plan the development of each of our communities if we are to foster equitable economic growth. We knew there was a sea-change underway with Mayor Harold Washington 30 years ago when we were there in the midst of it. Now, 30 years later, thanks to Hunt and DeVries, we can remember and better appreciate the reforms that “equity planning” was striving for and how urgently we need it again today.

“Chicago Works Together” was more than a political slogan at the time; it was a plan that focused on balanced growth and local jobs. However, that moment in time gave way, as Hunt and DeVries detail, to an absence of planning in which “deal making replaced clear thinking.” As they note, Chicago no longer has a city department with the word “planning” in its name. Their historical review does lead the reader to conclude that this may not bode well for the future.

Certainly, this history does provide justification for community skeptics to question, “Planning for whom?” Debates between downtown vs. neighborhoods continue but as Hunt and DeVries assert, it “understates the complexity of Chicago’s urban revival, missing the shared connections between the two.”

I found it remarkable to read how many big “downtown plans” never came to fruition, not because of opposition but because they suffered a bureaucratic slow death.

For non-Chicagoans, the chapters on the communities of Englewood, Little Village, and Uptown may not be as personally relevant; but they are well cast for comparisons between an African-American, Latino, and an economically divided community. The chapter on the Chicago Housing Authority’s transformation of public housing no doubt is playing out in a community near you. I know it is in mine.

Throughout their community chapters, Hunt and DeVries reference the Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC) New Communities Program, funded by the MacArthur Foundation. They appropriately credit the bottom-up planning process in developing “Quality of Life” plans for the New Communities Program.

I remain an advocate for leveraging business growth for local jobs, which is discussed in the planning for industrial retention and growth chapters. Jobs matter for quality of life. There is a vital role for nonprofits to play as delegate agencies of local government to perform neighborhood planning and pursue economic development.

I agree with Hunt and DeVries that “major adjustments are needed in Chicago’s industrial program—changes that a long-term planning perspective should guide.” The essentials of such planning must include land use for affordable business space, infrastructure investments for functionality, and workforce development for today’s and tomorrow’s jobs.

“Planning matters, as it has in the past,” Hunt and DeVries conclude. But it needs to be more strategic than what former Mayor Richard J. Daley reportedly told a member of the Chicago Plan Commission in 1968: “Get to the point to where the developers make money but don’t screw the city.”

Comments