However, there’s an interesting assumption underneath the VOSD’s “exposé”: That the taxpayers have somehow agreed that creating affordable units — wherever and however — is an end in itself, rather than a means of bettering people’s lives, creating economic inclusion, and promoting neighborhood stability.

It also assumes that short-term cost savings on a construction budget equals overall cost savings for taxpayers, when in fact, many of the costly items the article complains about will actually generate savings elsewhere or down the line. For example, universal accessible design allows for aging in place, which means less money spent on costly nursing home facilities. If market-rate developers are not spending on that kind of design, they are effectively creating healthcare costs.

Green design lowers utility bills, repair and replacement expenses, and healthcare costs. Locating near transit and in denser, opportunity-rich areas lowers residents’ transportation costs and increases their access to jobs and other opportunities for self-sufficiency. Along with making a stronger, more just society, these improvements strengthen local economies and save taxpayers money from other pots. We have a set of articles in this issue where we look into how those two sets of goals are being pursued in tandem.

On this theme we also have a web-only interview with Shelley Poticha, director of HUD’s Office of Sustainable Housing and Communities.

It’s difficult, of course, politically, to accept upfront costs to achieve savings decades from now, on other budget lines. Lifecycle accounting, as discussed by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, has been making inroads for a while in Europe, for example, in rules requiring appliance manufacturers to be responsible for disposal costs, which reduces incentives for planned obsolescence. What would it mean for housing developers to be responsible for the lifecycle costs of their design choices, and how would that influence the quality of housing at all income levels?

Accountability

Lenders and servicers need to be, and can be, partners in neighborhood stabilization (See Uncle Sam Outdone by Ocwen’s SAM). We’ll be delving into how capital markets can be brought to bear on bringing stabilization to scale in our next issue of Shelterforce.

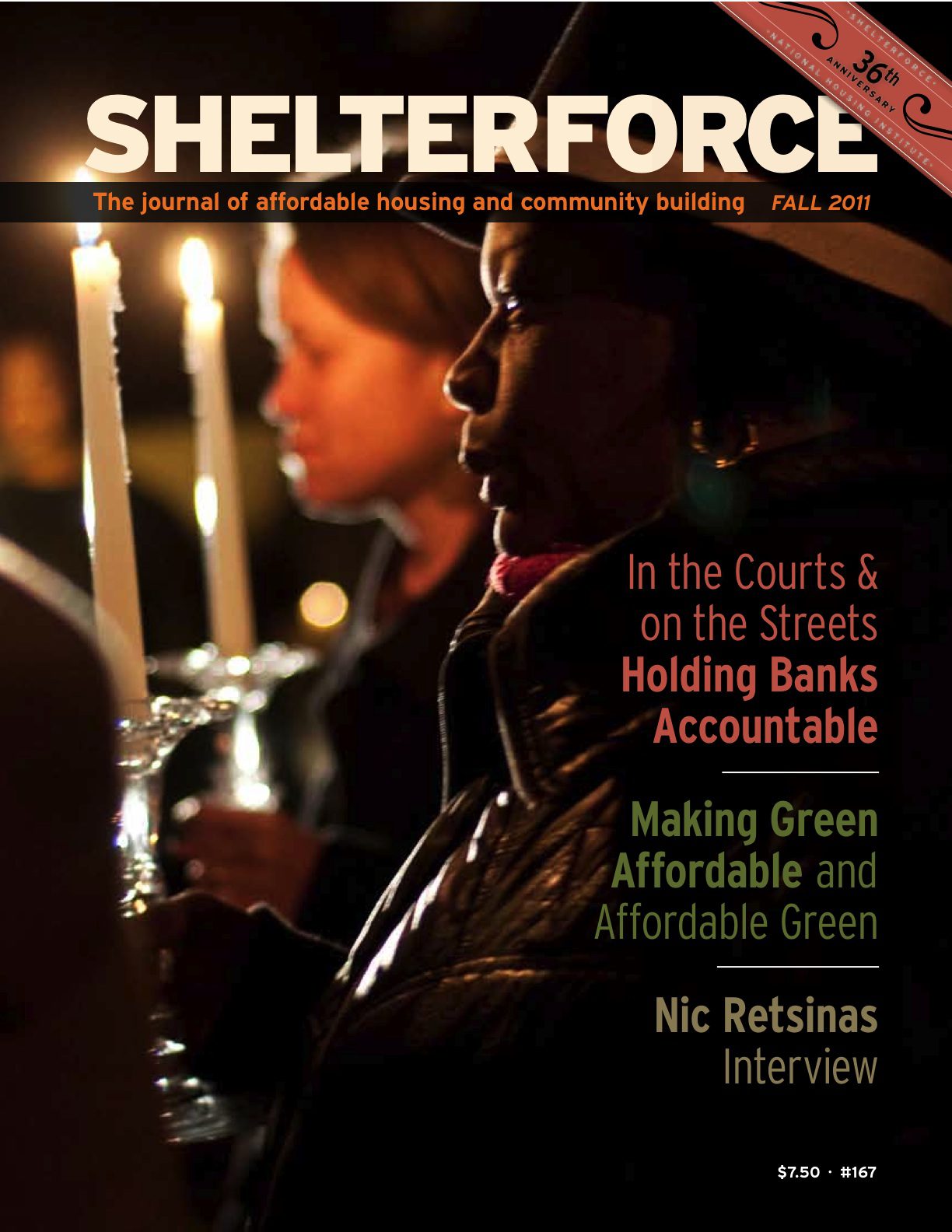

But even as there is partnership potential, the power relations between affected communities and financial corporations are still severely imbalanced, and communities continued to be harmed. The Occupy Wall Street movement emerged as we were wrapping up this issue — but they are not the first to be demonstrating, or even getting arrested, in the name of bank accountability. In this issue we hear from those trying to pile on the scales on the side of communities, seeking what Michael McQuarrie, writing about Ohio’s organizing group ESOP in our Spring 2010 issue, described as the “respect and recognition that comes from successfully negotiating an outcome to a confrontation — something that can never be achieved when confrontation is off the table.”

From California to Boston, organizers are weaving together actions as local and immediate as eviction blockades with campaigns to change the larger conversation about our financial systems. Meanwhile, inside the courts, judges like Cleveland’s Raymond Pianka have been getting creative in order to make the law stick to irresponsible speculators.

Keeping different scales in mind at once — whether in organizing, or thinking about both green materials and green locations — is difficult, but ultimately worthwhile. We’d love to hear from you about how you are knitting them together in your work.

Comments