From one perspective, the recent expansion of the Michigan’s 1990 Emergency Financial Management Act is just the latest salvo in a right-wing-led war against the rights of workers to organize.

The expansion will allow financial managers appointed to oversee bankrupt municipalities and school districts the rights to invalidate union contracts, dismiss elected officials, and dissolve municipal boundaries.

It sounds like extreme stuff. And it is. In the current political climate and when it would be carried out by governor appointees with little to no democratic oversight, the implications are really worrying. Looking at the behavior of Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker, and the assertions from many Tea Party Republicans about their disregard for the democratic process or collective bargaining rights, not to mention corporate tax breaks being passed at the same time, it is an understatement to say that it is hard to feel at all confident that the actions of Michigan’s emergency managers would actually be in the best interests of struggling cities—especially when those struggling cities are often Democratic strongholds.

That said, many of these cities are in serious, long-term distress, and they have been since well before the current financial crisis, even though that has pushed many to or over the edge. And actual fiscal collapse is also harmful to residents and workers.

As NHI senior fellow Alan Mallach, no Tea Party Republican, says, “There’s no question that the bill is draconian, and gives the manager extraordinary powers. On the other hand, it is a real possibility that situations will arise where they may be needed, including temporariliy setting aside collective bargaining agreements and imposing changes to workers’ salaries and benefits in order to be able to maintain minimum levels of public service, and in the most extreme cases, dissolving or consolidating municipalities.”

Mallach says there are two real problems with the bill, and neither are the rights it gives managers. One is the process: “The biggest problem is not that it permits these things to happen, but that it simply gives the manager the unilateral power to impose them, rather than establish a broader and more open process before such extreme steps can be taken.”

But even more importantly, Mallach says that extreme as these measures sound, they still seem to be assuming that the problems facing these municipalities are ones merely of accounting and management. Mallach says the problems are structural, based in greater economic shifts, changing markets, years of disinvestment, and fragmented regions. But the emergency management act, he says, “does not address the fundamental question of how – or whether – the viability of these places is to be restored, and then sustained.”

If you’re going to inflict this kind of pain on a population, it better be for a good cause, setting them on a path that will bring them some relief in the long term. I see little indication coming out of Michigan at this point that the state is interested in investing in strong, inter-connected, equitable metropolitan areas and addressing the hard questions of revitalization and right-sizing.

Our upcoming issue of Shelterforce, due out in about a week, will include looks at how equity is actually central, not disposable, in the search for economic recovery, and will explore some of the ways CDCs are adapting to better serve depopulated areas.

In the meantime, what do you think would be a democratic, equitable approach to municipalities about to fall into fiscal collapse?

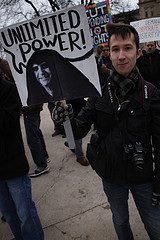

(Photo: Creative Commons BY-NC, Peace Education Center)

Comments