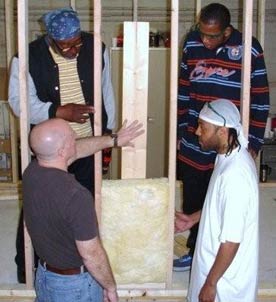

An El Mercado proprietor

Community, political, and business leaders — and in particular those with what are thought to be strong entrepreneurial skills — are often praised for their visionary leadership. This typically refers to their ability to see a future that is better than the present, in ways that others cannot. This ability enables such leaders to guide their enterprises in directions whose benefits are not readily apparent to those around them, but which nonetheless prove to be the right course of action. Such leaders can often steer their groups in significantly new or risky directions, without the level of scrutiny typically applied to ideas that are generated by those with less of a visionary reputation.

As the executive director of a community development corporation in Chicago in the early 1990s, I led the CDC, Bickerdike Redevelopment, in the development of a risky community economic development project that represented a radical diversion from what was then commonly accepted practice in the field. Our group had a well-deserved reputation as a CDC that was bold, progressive, and ready to challenge both conventional wisdom and the political power structure, and that consistently developed and managed its projects well. The new economic development project, while ultimately turned around into a highly successful venture, failed in its initial format. Did it, perhaps, fail because my colleagues and I let my visionary leadership win over my eyes-wide-open management and risk-assessment track record?

The Northwest Community Organization (NCO) established Bickerdike in 1967. Development in the community was stagnant after more than 40 years of neglect by the public and private sectors. In the late 1960s, the racial composition of the area was changing from primarily first- and second-generation European immigrants to Latinos and African-Americans, which occasionally spurred friction among residents.

NCO was one of the original community organizations set up by famed organizer Saul Alinsky in the 1950s and 1960s. He and his disciples practiced community empowerment through grass-roots organizing and challenging the power structures on issues ranging from crime to education to affordable housing and jobs. Bickerdike was created to enable the community to act in its own behalf with regard to the development of the physical community, and in particular affordable housing. At the time, and to this day, many in community organizing felt that becoming a developer — even a community-controlled nonprofit developer — was anathema to the spirit and culture of activist organizing. Alinsky-inspired groups like NCO felt that they should spin off and control the outcomes of community development groups, but not get mired in the actual operation of those spin-offs. Bickerdike’s work has resulted in the development of several hundred units of affordable housing.

Bickerdike had long recognized the importance of putting local people to work on its development projects. The group realized that its development activity represented a potential source of employment, and in an area of increasing joblessness and underemployment it seemed to make sense to address both the jobs and housing issues in the same projects. That notion summed up its understanding of “economic development”: that for area residents to benefit from economic growth there had to be access to both affordable housing and well-paying jobs. One example is its subsidiary, Humboldt Construction, which for more than 25 years has been providing union construction jobs and contracting services for the organization and others.

The group adopted a two-pronged approach to expanding its work on economic development. It would continue to be active with others in the community on an organizing and advocacy level, working to stem the loss of jobs and to try to achieve the maximum benefit of new developments in the area for local residents. And when it undertook a development project designed to have a direct economic impact, it chose projects that had the potential to catalyze additional positive development and demonstrate the benefits of community control and action.

Planned as a variation on a traditional Latin American marketplace, El Mercado was the group’s first project under those criteria. Neighborhood residents — who by the early 1990s were over two-thirds Latino — would be able to purchase fresh produce, meats, and prepared foods, local entrepreneurs would be able to have successful small businesses as operators of booths in the marketplace, and local residents would be hired to work those booths.

Bickerdike’s guiding criteria determined much of the pre-development planning for El Mercado and later became factors in the organization’s reluctance to alter its direction even when it became clear that it was floundering. El Mercado represented a significant deviation from the type of economic development efforts typically sponsored by CDC’s in Chicago and elsewhere. While there are many exceptions — and among those some of the most interesting projects to consider — most CDC-sponsored economic development projects are essentially real-estate ventures: the CDC develops the real property in much the same way as it develops housing, but in the case of economic development projects the tenants or end-users of the property are businesses that are expected to provide an economic stimulus to the area by creating employment or business start-up opportunities. Less common are projects where the CDC operates the business activity, itself becoming the direct agent for job-creation or business start-ups.

Comments