The church also built ties to grass-roots neighborhood organizations forming to combat the same ills church leaders were concerned about. Mulhern recalls when JPNDC wanted to build affordable housing on scattered sites, it asked her to accompany one of the agency’s organizers to meet with local residents. The organizer got a gold mine of information about which land was available and who to talk to. Residents trusted the church and figured if JPNDC had its blessing, that was good enough for them.

“In a sense, Blessed Sacrament was the heartbeat of the community. I knew who was there, who was poor, which house had water and which one had heat,” Mulhern says.

When gang violence erupted in the neighborhood in the early 1990s, Mulhern and some parishioners and neighborhood activists founded a group to organize peace marches and other anti-crime efforts. The group was successful in encouraging gang members to talk with their rivals. The Hyde Square Task Force, a youth organizing group that fights for more affordable housing and services for young people in the area, emerged from this effort.

For Blessed Sacrament’s leaders at the time, these forays into community activism were among the most vital elements of their work as theologians, according to Mulhern.

The Decision to Close

However, not all church leaders shared Mulhern’s point of view. In the 1990s, a new priest took the helm at Blessed Sacrament who did not have the same interest in community outreach, at least not if it meant getting involved in social issues. He spent much less time attending meetings with other community groups. He also made several changes in church policy, like charging a fee for use of the parish hall to non-church members. The effect was that the church’s relationship with the community was diminished.

Meanwhile, the demographic changes in the neighborhood, and in the church, that had begun decades earlier had accelerated. There were now few people at the English-language mass. The people who filled the pews were mostly Spanish speakers with origins in the Caribbean. While their faith was as fervent as that of the previous generation of parishioners, their pockets were comparably empty. Most lived on low incomes, lower than the whites who had now moved out of the neighborhood. When the offertory plate was passed around during services, few residents had much to give.

Blessed Sacrament was vulnerable, not only because of the relative poverty of its parishioners. The church also needed physical repair. Though the building had undergone major renovations in the 1950s, it had to be closed for two years during the 1990s after one of its pillars collapsed. Nearly a million dollars was spent to try to fix the problems, says Kathleen Heck, a project manager for the Archdiocese. But even this hardly put a dent in the maintenance costs.

The church’s physical size almost certainly played a role in the Archdiocese’s decision to sell it. Beyond the sanctuary itself, the surrounding campus included two church schools, a convent, and a rectory. Three of the buildings dated from the 1890s and the fourth from 1926. All the buildings had historical significance and, in Boston’s then-blazing real-estate market, very high dollar value.

But what really doomed Blessed Sacrament was that the people who were its lifeblood, the people who came to worship, lacked political power. Mulhern has a unique perspective on this, having moved in 2002 to run the religious education program at a Catholic church in the nearby Roxbury neighborhood. When the Archdiocese announced a list of churches slated for closure, both Blessed Sacrament and her new home were on the list. People who attended the Roxbury church traveled there from various sections of the city and could urge a broad cross-section of political leaders to lean on the Archdiocese to keep their church open.

“We were able to go to the neighbors, the agencies, the mayor, our own constituency, and say, ‘we’re too important, you can’t close us,’ “ says Mulhern. “But Blessed Sacrament didn’t have that kind of clout. It had lost it.”

Keeping the Church in the Community

The JPNDC was the obvious choice of many people in Jamaica Plain to make a bid to buy the church and the other four buildings. Twenty-five years after it made its first major purchase, a shuttered brewery complex that it turned into retail shops and offices, the organization has a deep well of respect in the community. While its major work has been to acquire neglected property and redevelop it as affordable housing, it has also collaborated with other activist groups in the area to save subsidized housing properties from going to market rate.

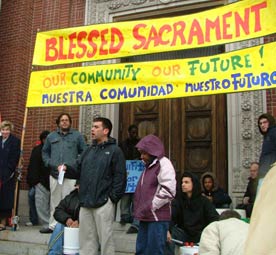

JPNDC called on its core supporters to rally in support of the proposal to buy the church. Others in the community, including Hyde Square Task Force and a grass-roots tenant organizing group, City Life/Vida Urbana, lent their forces to the effort. It was by no means certain that the Archdiocese would be willing to sell to a nonprofit.

Comments